An 18th century candy made with white pepper, brandy and sugar.

An 18th century candy made with white pepper, brandy and sugar.

My first book, Eight Flavors: The Untold Story of American Cuisine will be released December 6th, but is available for pre-sale right now. To create the book, I researched the eight most popular flavors in American cooking: black pepper, vanilla, chili powder, curry powder, soy sauce, garlic, MSG, and Sriracha. When I dived deep into each of these eight topics, I often found fascinating new information and recipes–some of which didn’t make it into the book. So over the next few months, I’ll be publishing this exclusive content on my blog! If it whets your appetite to read the whole book, make sure to get your own copy here.

In the 21st century, black pepper sits firmly on the savory shelf of our kitchen. We add a twist from our peppers grinders to finish a salad, or crust the exterior of a thick steak with cracked peppercorns. But as I was researching Eight Flavors, I discovered pepper was used to complement sugar, just as often as it was used with salt.

Last week, I got the chance to do some of my first public speaking engagements in California, including a visit to the Dallidet Adobe in San Luis Obispo, California. As part of my talk, I made “pepper-cakes” from the 18th century, a simple candy made of pepper, alcohol and sugar. Easy enough to make, with an intense, but pleasant flavor.

The History

An early American reference to pepper used in sweets is found in Hannah Glasse’s The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, first published in 1747 in England. This book was an extremely popular import to America, and also went through several domestic printings, with an added chapter on the use of American ingredients. In the first American edition in 1805, Glasse uses pepper in her pickles, fish recipes, and in many, but not all, of her meat recipes, often in combination with nutmeg, mace, cloves, parsley, savory, and thyme.

But tucked in next to recipes for cookies and gingerbread is this recipe:

To make pepper cakes.

Take half a gill of sack, half a quarter of an ounce of whole white-pepper, put it in, and boil it together a quarter of an hour; then take the pepper out, and put in as much double refined sugar as will make it like a paste; then drop it in what shape you please on plates, and let it dry itself.

The recipe is more of a candy than a cake: brandy is infused with pepper, mixed with sugar and left to dry. Sack is an old word for brandy, and a gill is a measurement of four ounces. So this recipes calls for 1/8 ounce white pepper, boiled for 15 minutes in 2 ounces (1/4 cup) of brandy. I suspect Glasse choose white pepper so as not to discolor the brandy; white pepper was prized historically because it kept white sauces (or in this case, white candy) looking clean and white. I decided to give this unusual recipe a try.

The Recipe

My tiniest saucepan is actually a two-cup measuring cup, perfect for my quarter cup of brandy and smattering of white peppercorns. I set it on my gas burner, and turned the flame up to high to bring the liquid to a hard boil. But after about two minutes of heating–it ignited!! A jet of flames leapt an impressive three feet into the air, flickering blue and gold, almost igniting my eyebrows in the process. Oops. I wonder why Hannah Glasse didn’t warn me about that?

Rather than smothering the flames, I turned off the burner and let it do its thing. The flames would burn off the alcohol, as well as infuse the aromatic oils from the pepper. It burned itself out in a couple minutes, and I strained the brandy into a glass bowl.

At this point, the smell of the white pepper infused brandy was very strong: musty, like old attic books. I added 1 ½ cups white sugar and mixed it into a paste. Glasse says “drop it in what shape you please on plates,” so I used a mini ice cream scoop that I normally employ for doling out cookie dough. I shoveled tiny mounds of pale, cognac-colored sugar onto parchment-lined baking sheets, and set them aside to dry.

The Results

The next morning, the little sugar balls were crusty and shockingly beautiful. Since the sugar is not cooked, the candy isn’t hard and smooth; instead, it’s crisp, crumbly, and sparkly! It looked like the top layer of snow: slightly melted, glistening in the sunshine. These simple treats were breathtakingly beautiful.

But tasted terrible.

I popped one in my mouth. Imagine the taste of musk. Something musky. White pepper is awful. It’s awful.

I hated the taste but loved the concept of this candy. So a couple quick substitutions, and I had made a vast improvement: instead of brandy, I used a sweet white wine. To replace the white pepper, classic Tellicherry black peppercorns offered a complex and surprisingly pleasant flavor.

Give this candy a try for a unique treat and what will seem like a totally innovative way to use pepper– that’s actually over 200 years old.

White Wine and Black Pepper Snow Drops

Adapted from The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, by Hannah Glasse, 1805 edition.

¼ cup sweet white wine

1 teaspoon black peppercorns

1 ½ cups white sugar

Yield: makes 40-60 candies

- Combine wine and pepper in a small saucepan; place on a stove top burner on high. Cover. Boil for five minutes.

- Add sugar, stir to combine. Drop into ½ teaspoon sized balls onto a parchment lined cookie sheet.

- Allow to dry completely. This part of the process can be complicated on a humid day, resulting is a sticky, never-quite-dry candy. If you can, make this candy in the winter, or used a well-airconditioned room.

Spruce limbs.

Spruce limbs.

The History of Garlic: A Special Dinner at the Farm on Adderley

The History of Garlic: A Special Dinner at the Farm on Adderley Distilling Brooklyn

Distilling Brooklyn Moose Milk: A drink for a blizzard.

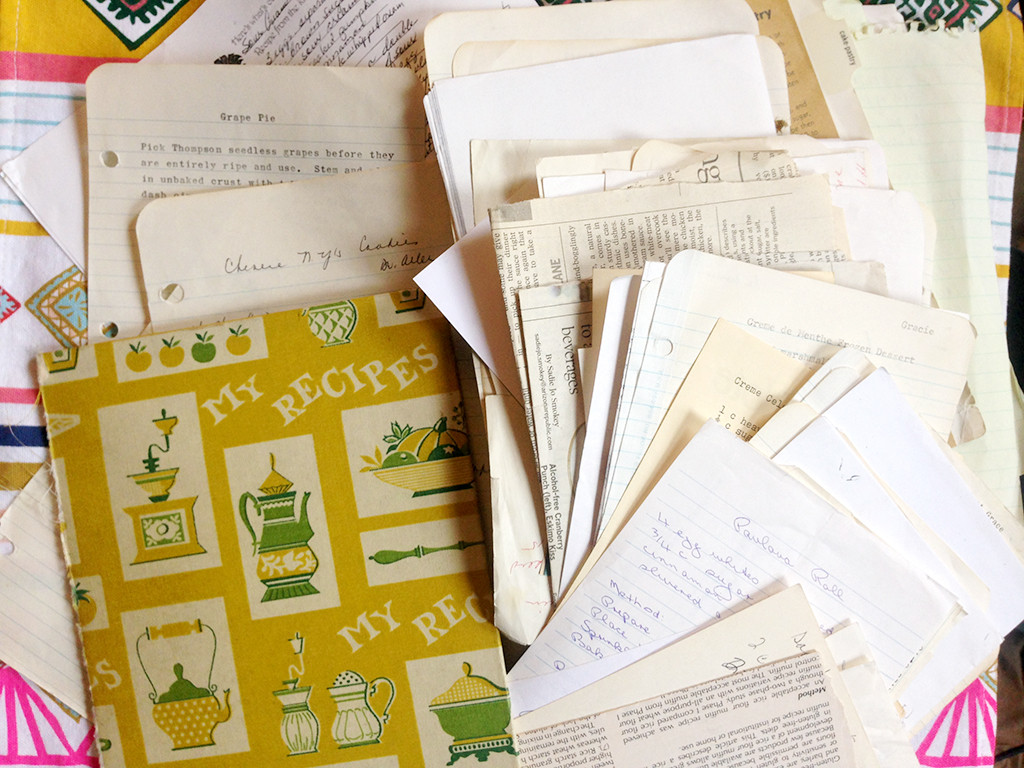

Moose Milk: A drink for a blizzard. A recipe collection dating from 1966-1998.

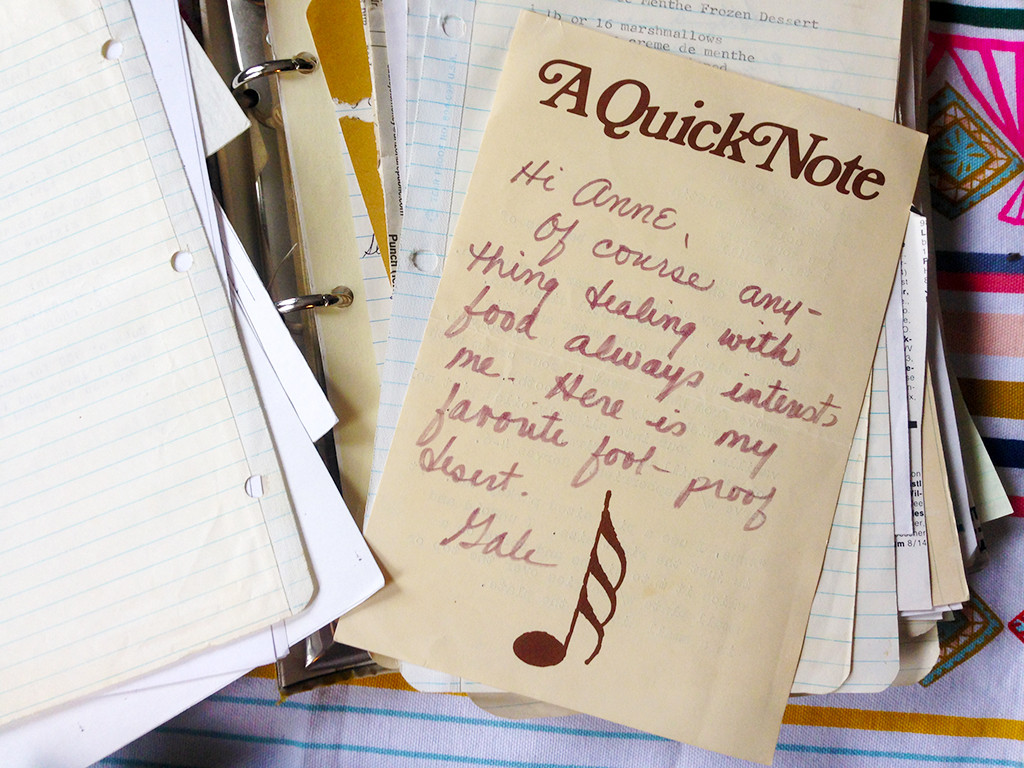

A recipe collection dating from 1966-1998. Gale’s fool-proof dessert is C

Gale’s fool-proof dessert is C I included some of my parent’s homemade, dark

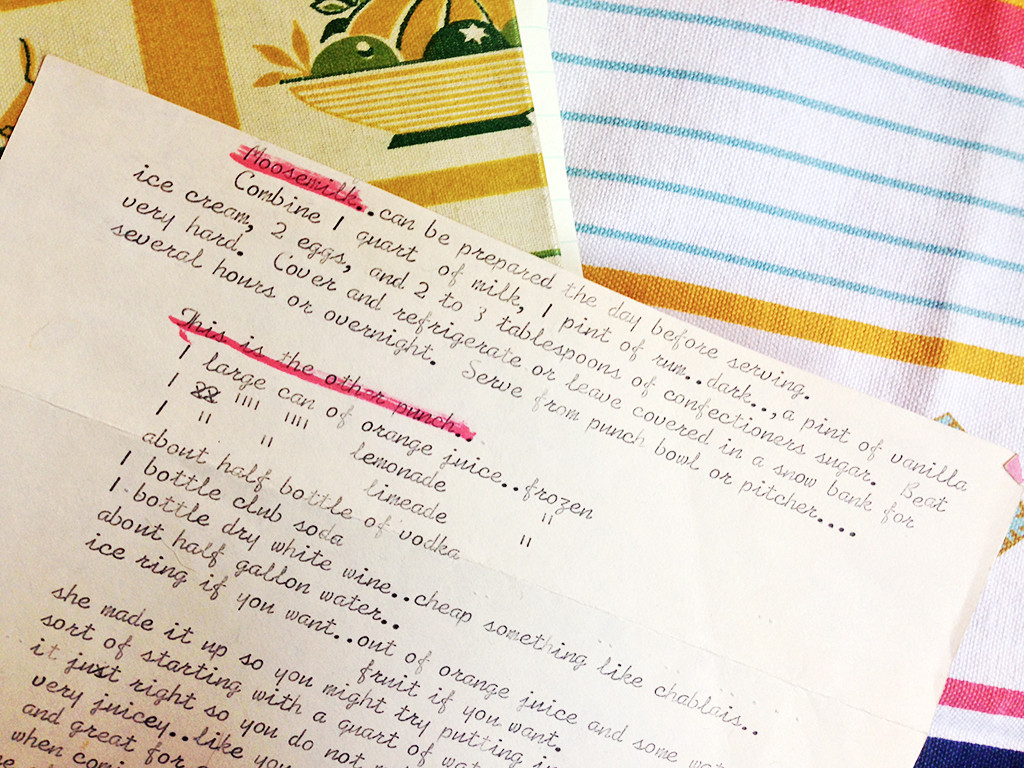

I included some of my parent’s homemade, dark  The original recipe for Moosemilk.

The original recipe for Moosemilk. Putting the punch to bed. See the blue circle of the punch bowl on the ground?

Putting the punch to bed. See the blue circle of the punch bowl on the ground? The next morning: Covered in a snow drift!!!

The next morning: Covered in a snow drift!!! Excavating the punch.

Excavating the punch. The final punch!

The final punch! Two bottles of beer brewed with real spruce limbs.

Two bottles of beer brewed with real spruce limbs. A home-brewed ginger beer.

A home-brewed ginger beer.