Breakfast

Fresh Fruit

Sardines

Bread & Butter

Coffee

Dinner

Barley

Roast Meat

Vegetables

Bread

Supper

Beans (Baked by Mrs. Paley)

Cakes

Bread

Tea

Mrs. Paley, if you’re curious, was the head of the Ellis Island Kosher Kitchen, although I was unable to find her original baked beans recipe.

Getting out the breakfast dishes on my last day made me a little bit sad. I had quickly grown used to ritual and the relaxed breakfast my boyfriend and I shared over the kitchen table. It was somehow different over hurried bowls of cereal.

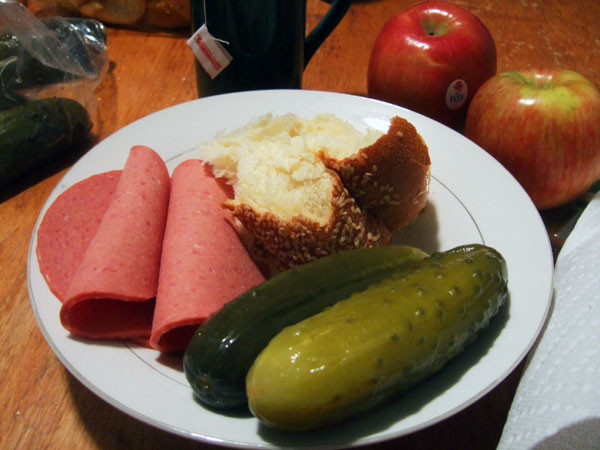

However, if you think I was excited to have sardines for breakfast, you are wrong. I must admit, they tasted better than they smelled: the flavor was much like a very mild tuna. However, I’m also not accustomed to having tuna for breakfast.

For lunch and supper, I wanted to change the menu up a little bit. This menu is actually for a Wednesday in the Ellis Island Kosher Kitchen and I wanted to keep closer to tradition. Friday is a special day–sundown marks the start of shabbat.

For lunch, we had Streit’s Mushroom Barley Soup, a kosher, dry soup mix. It was easy to make, incredibly cheap ($1 a serving) and really delicious. Who knew? I am definitely going to make it again.

I needed to measure four cups of water to add to the soup mix. My metal, two-cup measuring cup was treif, meaning I had used it with both meat and dairy, so I dunked it in boiling water. Certain materials can be cleaned for kosher: glass needs a thorough scrub with good hot water; a metal fork or knife that has become treif can be cleaned in boiling water. More porous materials, like porcelain, enamel, and wood, cannot be cleaned if kitchen mistakes are made. And kitchen mistakes are made: today, while cleaning the lid to my meat pot, I carelessly grabbed the everyday kitchen sponge, not the meat sponge. One touch to the pot lid and it was ruined. Luckily, it’s made of glass and metal: a dunk in boiling water, and we’re in good shape again.

For dessert, I busted out our only real sweet treat of the past three days: Babka. I bought a slice of cake from a kosher bakery on a stretch of Grand street that is an island of Jewish tradition. I walked into the shop, cakes behind glass displays calling my name. A round woman with jet black hair wrapped in a hair net asked if she could help me.

“What’s this one?” I asked, pointing to a glossy brown cake covered in walnuts.

“Babka! Walnuts, raisins, cinnamon.”

I thought it over. “Hm. I need a couple of slices of something delicious.”

“This is very delicious!” She responded. And it was.

Babka!

Babka!

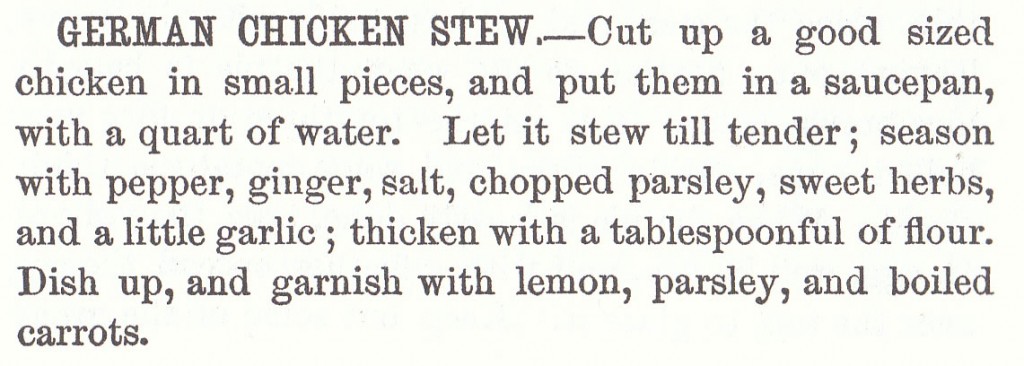

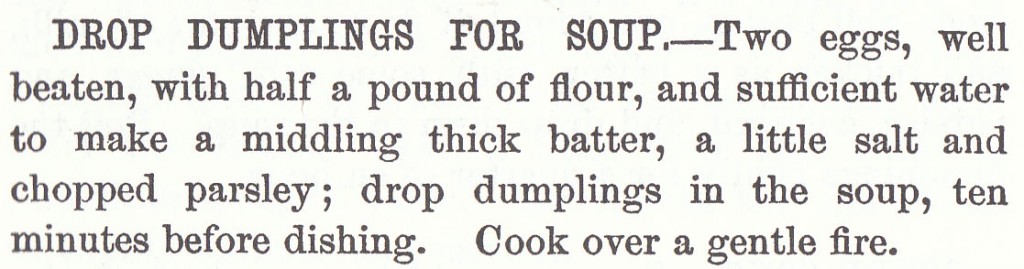

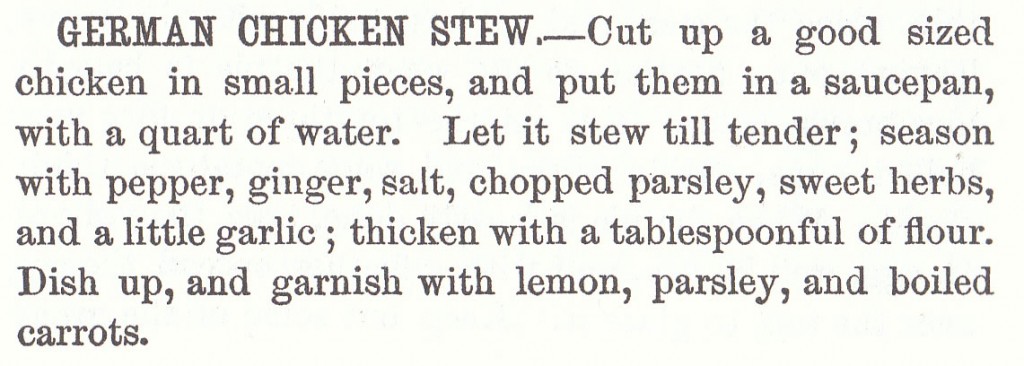

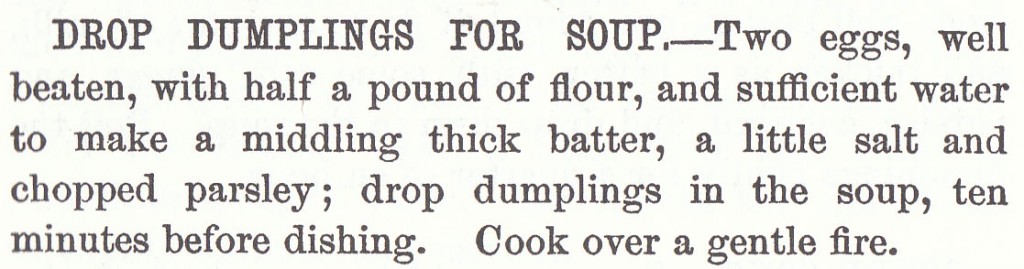

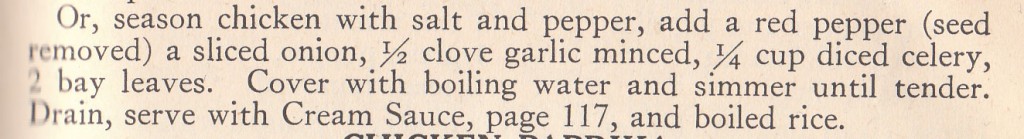

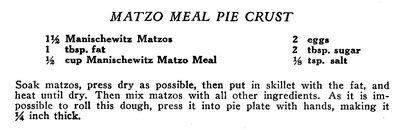

Friday night supper is very important. When the sun sets tonight, I’m lighting the candles and keeping shabbos: the day of rest that lasts from sundown Friday to sundown Saturday. Sunset is at 7:28; so the candles will be lit at 7:10. Before the candles are lit, dinner must be ready. And what is more appropriate for the Sabbath then a hot bowl of chicken soup? The recipe I’ll be cooking from comes from the first kosher Jewish cookbook published in America, Jewish Cookery Book by Mrs. Esther Levy (1871), “A cookery book properly explained, and in accordance with the rules of the Jewish religion.”

There’s 39 categories of things I am not allowed to do on shabbat (although I may employ Roommate Jeff as a shabbes goy). The list includes cooking, tidying, plowing, weaving, writing two or more letters, building, demolishing, extinguishing a fire, kindling a fire, putting the finishing touch on an object and transporting an object between the private domain and the public domain. It’s all based around preventing one from doing work and encouraging one to rest.

Tonight, we will turn off the lights, the computers, the cellphones and the tv. We’ll read by candlelight, rest, and attend to certain other encouraged activities.

Tomorrow, I’ll break sabbath by getting up, getting on the train, and going to work. When I step out the door, I’m shedding the rituals a life that is not mine; but I’m leaving with a much better understanding of what it entails.

At the Lower East Side Tenement Museum with a photo of the historic character I portray (far right). Photo by Will Heath.

At the Lower East Side Tenement Museum with a photo of the historic character I portray (far right). Photo by Will Heath.

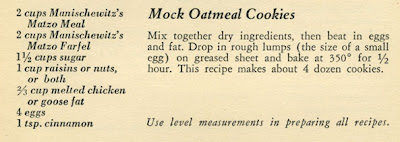

most New York matzo balls are fist-size, like the ones you’ll find at Katz’s or the 4th Ave. Deli. These featherballs were to be rolled the size of walnuts. Their are also two types of matzo balls–the light “floaters” and the dense “sinkers.” Neither are wrong, just a personal preference.

most New York matzo balls are fist-size, like the ones you’ll find at Katz’s or the 4th Ave. Deli. These featherballs were to be rolled the size of walnuts. Their are also two types of matzo balls–the light “floaters” and the dense “sinkers.” Neither are wrong, just a personal preference.