A “Funeral Card,” given to guests of a 19th c wake.

Eating our Emotions: The History of Food in Funeral Traditions

Sunday, October 7th, 2:30 pm

@ The Queens Historical Society

Free (but please RSVP here so I know how much food to bring!)

A “Funeral Card,” given to guests of a 19th c wake.

Eating our Emotions: The History of Food in Funeral Traditions

Sunday, October 7th, 2:30 pm

@ The Queens Historical Society

Free (but please RSVP here so I know how much food to bring!)

This is what black pepper looks like just after it’s harvested. Who knew?

This is what black pepper looks like just after it’s harvested. Who knew?There is the gradeschool myth that Far East spices, including pepper, were used to cover the taste of rotting meat. But recent scholarship suggests that if a family could afford spices from the Far East, they could also afford freshly slaughtered meat–which logically, makes sense.

However, the old legend may not have been entirely wrong, just misinterpreted. A 1998 study by Cornell showed that black pepper, as well as many other spices, have antimicrobial qualities. Ground white and black pepper kill up 25% of bacteria they come in contact with, although pepper doesn’t hold a candle to garlic, onion, allspice and oregano, which kill 100% of bacteria. So, perhaps meats of the Middle Ages weren’t highly spiced to hide the flavor of rotten meat, but to actually stop the meat from rotting.

Pepper, therefore, acts as a preservative by keeping microorganisms at bay. Early Americans seemed to be aware of pepper’s preservative properties. There’s a bizarre story recounted in the 1949 book Pepper and Pirates of a seafaring man who died far from home in the early 19th century, and he “was shipped back to Salem in a coffin filled with pepper.” Apparently, his body made it back little worse for the wear.

Welcome to the Griddle Picnic. In the Antebellum days, river showboats would pull up to Aunt Jemima’s plantation, and she would serve them hamburger and fankfurter pancakes. That all makes perfect sense.

***

I found this image here!

Just Heat It ‘n’ Eat It!: Convenience Foods of the ’40s-’60s

That’s the advice professor Charles Bergengren gave students on commencement day 2012 at the Cleveland Institute of Art.

That’s my alma mater, and Charlie is my old professor. He passed away very suddenly and unexpectedly just two months after giving this speech. In the void of his absence, I realized just how much he has influenced me as an artist. As an expert in folklore and vernacular art, he’s the one that made me think of food as art for the first time. I did my first piece of culinary historical writing for him. He advised my thesis work and inspired me to walk 500 miles across Spain after I graduated.

I miss him.

Watch this video (skip to minute 2:20 for the start of Charlie’s speech). In five minutes, he’ll make you a better researcher. And he may even inspire you to do something radical.

The Master of Social Gastronomy Get Shelved: Preservatives and Convenience Food

The Master of Social Gastronomy Get Shelved: Preservatives and Convenience Food

Tuesday, September 25th, 7pm

@ Public Assembly, Williamsburg, Brooklyn

FREE (but please RSVP here!)

MSG is our FREE monthly food science and history lecture, and this time we’re talking all about convenience food!

It’s evil, right?

Well, you may change your tune after Sarah’s Ode to Convenience Food in Three Parts: How Convenience Food Won the Civil War; How Convenience Food Almost Killed Us at the Turn of the Century; and How Convenience Food Liberated the Modern Woman.

Sarah is fairly certain modern society was built on the back of Borden’s Sweetened Condensed Milk, and at MSG, you’ll find out why.

Why does your bacon clamor about its lack of nitrites, but your soda keeps quiet about sodium benzoate? Soma will unwrap our love/hate relationship with modern preservatives, and how keeping our food safe may or may not kill us in the end. Learn to read the small print of food labeling with terrifying ease!

Please RSVP here, so we know how many free samples to bring!

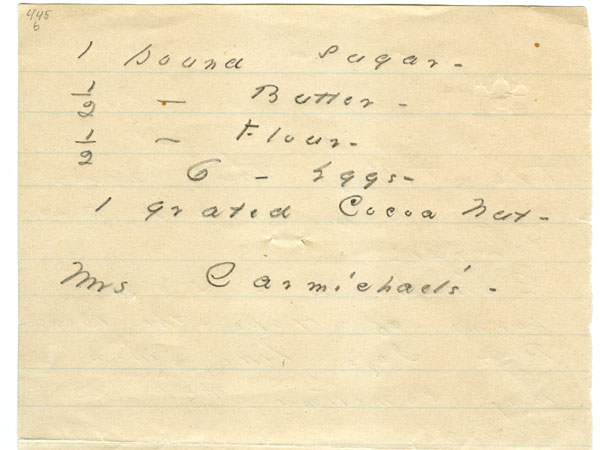

Recipe or poem? Emily Dickinson’s recipe for “Cocoa Nut” cake. 445B: courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections by permission of the Trustees of Amherst College.

Recipe or poem? Emily Dickinson’s recipe for “Cocoa Nut” cake. 445B: courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections by permission of the Trustees of Amherst College.We’ve got a guest post this week from Aife Murray, author of Maid as Muse: how servants changed Emily Dickinson’s life and language— and I want to let you jump right into it. Read on for a story about Dickinson the poet/cook who would give you the recipe to make a prairie just as soon as she would her recipe for cocoanut cake.

Aife recently spoke about Dickinson at the Lower East Side Tenement Museum. The video of this event is here.

“Waste not, want not” was a maxim in Emily Dickinson’s kitchen. Her family’s well-thumbed housekeeping manual, The American Frugal Housewife by Lydia Maria Child, from 1844, begins this way: “The true economy of housekeeping is simply the art of gathering up all the fragments so that nothing be lost. I mean fragments of time as well as materials.”

Emily Dickinson grabbed every conceivable scrap of paper for her stationary. She wrote poems on the backs of party invitations, bills, recipes, shopping lists, food wrappers(think the chocolate bar wrapper made famous by Joseph Cornell) — the kinds of paper that seem to

“grow” on any kitchen counter. She’d use these scraps to capture a poetic idea that had skidded into the imagination. When my hands are busy grating nutmeg or scrubbing the stove my mind roams broadly and I receive what feel like “gifts” of ideas (Buddhists would call that “naturally occurring wisdom”). In Emily’s case, what rose up might be a great poem. So she gathered up even those fragments of ideas for poems and jotted them on the backs of those fragments of paper collecting by her pantry board.

Emily Dickinson (source)

Another frugal idea, adopted by prize-winning baker Emily Dickinson, came from the sewing room. In order to keep her kitchen-writing life in place she pinned recipes into her cookbook. I’m a tactile learner too. Among the cookbooks on my bookshelf I tuck recipes I’ve torn from magazines or jotted on the back of an envelope when talking food with a friend. Of course those papers are at risk every time I grab a cookbook (but they remind me, as I pick them up, about a dish to try). Perhaps Emily Dickinson had a better idea. She used a simple straight pin to hold these various slips of paper into her family cookbook. She not only pinned recipes but she pinned her poems together.

Emily’s original of the coconut cake recipe, below, has two small pin holes in it. On the reverse of the recipe she began writing the poem “The things that never can come back” but then the poem got longer and she grabbed another sheet of paper to finish it. And so, as she might pin a recipe together in her “receipt book,” she took a straight pin to keep the pieces of the poem together. Look at the dashes in this recipe – she’s famous for using dashes (which came first? The recipe dash or the poem dash?):

1 Pound Sugar –

½ Pound Butter –

½ Pound Flour –

6 – Eggs –

1 grated Cocoa Nut –

It turns out inspired writing is a lot like inspired cooking. And Emily Dickinson easily adapted kitchen practices to her writing. Recipes — a simple list with proportions — are as concise as poetry. I think recipes were a suggestive form for Emily Dickinson, just as much as sonnets or haiku. Doesn’t her coconut cake recipe look an awful lot like this “recipe” for mixing up a prairie?

To make a prairie it takes a clover and one bee,

One clover, and a bee,

And revery.

The revery alone will do,

If bees are few.

***

Read More!

Maid as Muse: How Servants Changed Emily Dickinson’s Life and Language (Revisiting New England)

Monday, September 17th, 6:30 PM

Where: Brooklyn Brainery, 515 Court St., Brooklyn, NY.

Tickets: $45, Get ‘em Here

‘I’m not talking a cup of cheap gin splashed over ice cubes. I’m talking satin, fire and ice. Fred Astaire in a glass. Surgical cleanliness. Insight and comfort. Redemption and absolution. I’m talking a martini.” -Anonymous

In essence, that is what this class is all about. Looking at both vermouth and the martini we will track the interlocking history of both beverages in this three hour master class. We’ll start with a vermouth tasting, and talk about vermouth’s origins in 1,000 BC to the invention of the Martinez in the late 1800’s (the Martini’s predecessor).

In addition to history, we will discuss different grapes and botanicals used in vermouth, why that bottle of vermouth you’ve been holding onto for a year tastes horrible, and how Churchill drank his martinis.

Then, we’ll mix three different versions of the Martini. You’ll learn the steps to make a perfect drink, sampling three different adaptations from three different eras. Through a bit of tasting, you’ll see how the recipes have changed over time, and be able to adopt your own James Bond-like preferences.

Sign up here!

I’m demoing a turn-of-the century recipe for Chop Suey tonight, as well as talking about Chinese-American cuisine and the history of New York’s Chinatown. It’s all FREE. Come by tonight, or catch this talk on the Lower East Side November 3rd.

Chinatown and Chop Suey – in part with the NYPL’s Lunch Hour NYC

Chinatown and Chop Suey – in part with the NYPL’s Lunch Hour NYC

Thursday, September 13, 5:30 p.m.

Morningside Heights Library – Community Room

2900 Broadway, NY NY

and

Saturday, November 3, 10:30 AM

Seward Park Library

192 East Broadway, NY NY

FREE

Chinatown and its cuisine have always been a lunchtime favorite. In this talk, we’ll chat dim sum and tea houses, the Jewish connection to Chinese food, and the history of Chinatown as a cheap lunch destination. Live demo (and tasting!) of a 19th century recipe for the “original” Chop Suey, featuring chicken livers and gizzards.

A witch’s broom re-purposed as a whisk.

A witch’s broom re-purposed as a whisk.I’ve launched a new collaboration with Etsy this week: I’ll be blogging twice a month about making, doing and consuming in the kitchen. Look forward to history and adventures, all based on the treasures you can find on Etsy.

My first post was a whisk history–a humble kitchen tool that has changed design over the centuries, striving to make a laborious task, like beating eggs, simple and succinct. Read The Magic Whisk here here to follow me whisking up meringue by hand.

But before wire whisks were introduced in the 19th century, cooks made whisks from bundles of sticks. You can still buy modern whisks made with birch twigs, but they are fairly expensive: $20-$30. I was really curious to try one out, and test it against a modern whisk, but I had difficulty convincing myself to drop three tensies on sticks. Reading this, you probably think I’m nuts: “Go outside, get some sticks!” you’re thinking. Well, I live in New York and things aren’t so simple. In my neighborhood, I can get food from 30 different nationalities; But sticks we don’t got.

Recently, I had a chance to handle one of these birch whisks in person. I carefully turned it over in my hands, committing to memory the length and the weight of it, the texture and the stiffness of the straw-like twigs. Then I went to my local craft store to see if I could find something to replicate it. I noticed the store already had its “seasonal items” out and immediately thought “witch’s broom!” I scored one for $6. To make my reproduction whisk, I sliced off the tape that held bushy twigs them to the broom handle, rebundled them with kitchen twine, and trimmed the ends to an even length. It looked almost exactly like the authentic $30 whisk, and seemed to be a pretty good recreation of a pre-industrial whisk.

It was time to try out my pre-industrial whisk. I separated an egg, and set aside the yolk. I let the white warm to room temperature in a deep mixing bowl, and then I grabbed my twig whisk and went to town. It took a surprisingly short amount of time to make a stiff meringue–ten minutes, twelve seconds–although my biceps ached after half a minute. The twig whisk had a huge downside: as I whipped the eggs, hundreds of shards of whisk broke off into my meringue. Big sticks and tiny twigs peppered the egg froth. It’s possible that after you use the twig whisk several times, it would stop shedding its bits and pieces. But the first time through, it produced a voluminous, but woody, meringue.

A twig whisk and the woody meringue it produced.

A twig whisk and the woody meringue it produced.I tested four more whisks and pitted them against my modern mixer; to see the results, head over to Etsy.

The Masters of Social Gastronomy podcast talks the science and history of GELATIN!

Sarah will discuss the origins of gelatinous desserts, starting long ago when jiggly delights were made with drippings from beef stew or extracts from the swimbladders of sturgeon. Then she’ll take on that modern wonder: Jell-O! She’ll explore the greatest atrocities and wildest successes of the 20th century Jell-O mold. From 19th-century “Punch Jelly,” to 20th-century “Jell-O Sea Dream with Shrimps” you will hear about gelatin both beautiful and horrible.

Then, Soma will untangle the science of gelatin and its kin, introducing a few lesser-known relatives along the way. How’d we get the wiggle in those jigglers? Find out where killer bacteria and Jell-O meet on the other side, and dive into the amazing world of edible dishware. Stretch the boundaries of reality through an introduction to counterfeit Chinese eggs and the fancy-pants world of molecular gastronomy.

You can subscribe to the MSG podcast via ITUNES here.

__________________________

Read More!

Hello, Jell-O!: 50+ Inventive Recipes for Gelatin Treats and Jiggly Sweets

Jelly Shot Test Kitchen: Jell-ing Classic Cocktails-One Drink at a Time

Origin of a Dish: The Jell-o Shot