I went on a pilgrimage of sorts this weekend.

I went on a pilgrimage of sorts this weekend.

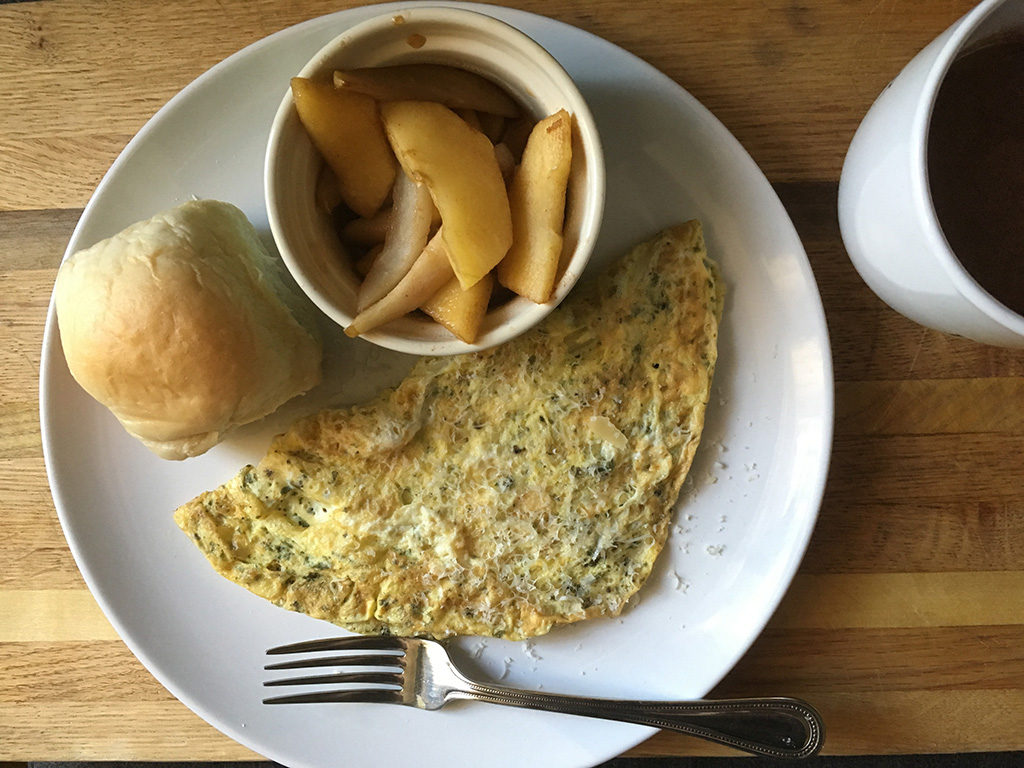

Breakfast

On Saturday, I woke up at a Bed & Breakfast near Rochester. I was speaking at a conference that afternoon, and part of the deal was my room and board. So when I wandered downstairs to the quaint dining room, I didn’t stick to my diet. I ate what they gave me. I had a cup of black tea, which I had really missed this week, as well as a homemade jelly donut, a slice of apple cake, yogurt, and a ham and cheese souffle.

Before I went to the conference, I wanted to make a special stop: I was close to Mt. Hope Cemetery, the final resting place of Susan B. Anthony. Anthony founded the National Woman Suffrage Association in 1869, but her grave site was recently in the news because hundreds of women stopped by to stick their “I Voted” stickers on her grave. The cemetery decided to stay open late on Tuesday to give women the chance to do so. Check out this PBS article to see incredible photos of her gravestone covered in stickers, and the long line of women waiting to add their badge.

I had preserved my “I Voted” sticker, because I felt I wanted some physical reminder of what had happened Tuesday. When I realized I would be near her grave site this weekend, I knew this was a pilgrimage I had to make. After driving to the cemetery, the trees in high-fall colors, I walked up to silent grave and dutifully stuck my sticker to the grave. The other stickers had been cleared away; mine was the lone reminder.

Before too long, a young woman walked up, probably from the nearby University of Rochester, wearing a camera around her neck and a shirt that said “Women Belong in the House and the Senate”. She commented she was sad the stickers were gone; I told her I had traveled from NYC to add mine.

“Frederick Douglass is here too, do you know that? His grave-site is amazing.”

“Yes, I passed him on the way here. I noticed he has a big plaque. But I’ve been wondering where Susan’s plaque is.” The sight of Douglass’ grave had made my heart sing, but feel a little confused when I approached Anthony’s. Other than a few signs to direct visitors to her grave, there was no other information or fanfare.

“Yeah. It shows even now how we treat men and women differently, even though they fought for the same things,” she answered, then added hesitantly: “…I’m sorry, I’m a feminist.”

“Anyone standing at this grave site at 9am on a Saturday is a feminist.” I responded.

Before I left, a mother and her grown daughter joined us in front of the grave. We all stood there silently, looking at the head stone. Then I walked back to my car and sobbed in the front seat.

If I could write Susan B Anthony’s plaque, here’s what it would say: “I think she would be proud of how far we’ve come, but perhaps she would be sad at how far we have left to go.”

I also visited the grave site of Lillian Wald. Wald founded the Henry Street Settlement and the Visiting Nurses service, a group of young, college educated women that were the first organization to provide affordable health care, in this case to new immigrants on the Lower East Side of Manhattan.

Wald was also a lesbian. Settlement Houses and social work were considered a socially acceptable job for women with a college education who wanted to delay, or defer, marriage. If you weren’t taking care of your own husband and children, then it was seen as honorable to “sacrifice” those goals to help the children of the world. But Settlement Houses also became a place for any women who wanted to escape traditional gender roles and sexual expectations. It was a safe place for women who wanted to be with women, whether as colleagues or lovers.

In her 1915 book, The House on Henry Street, Wald described her awakening to the cause of social justice; sentences in bold are my own added emphasis:

I had spent two years in a New York training school for nurses; strenuous years for an undisciplined, untrained girl, but a wonderful human experience… I had little more than an inspiration to be of use in some way or somehow, and going to the hospital [on the Lower East Side] seemed the readiest means of realizing my desire…The Lower East Side then reflected the popular indifference—it almost seemed contempt—for the living conditions of a huge population. And the possibility of improvement seemed, when my inexperience was startled into thought, the more remote because of the dumb acceptance of these conditions by the East Side itself. Like the rest of the world I had known little of it, when friends of a philanthropic institution asked me to do something for that quarter…

From the schoolroom where I had been giving a lesson in bed making, [ed note–a lesson in nursing for local families on the LES] a little girl led me one drizzling March morning. She had told me of her sick mother, and gathering from her incoherent account that a child had been born, I caught up the paraphernalia of the bed making lesson and carried it with me.

The family to which the child led me was neither criminal nor vicious. Although the husband was a cripple, one of those who stand on street corners exhibiting deformities to enlist compassion, and masking the begging of alms by a pretense at selling; although the family of seven shared their two rooms with boarder— who were literally boarders since a piece of timber was placed over the floor for them to sleep on,— and although the sick woman lay on a wretched, unclean, bed soiled with a hemorrhage two days old, they were not degraded human beings judged by any measure of moral values…Indeed my subsequent acquaintance with them revealed the fact that, miserable as their state was, they were not without ideals for the family life and for society of which they were so unloved and unlovely a part.

That morning’s experience was a baptism of fire.

I hope this election is our country’s baptism of fire. It has been an awakening to me that I need to do more, everyday, to fight for the disenfranchised. I hope, as a country, these feelings don’t fade after a few weeks. I hope they build steam over the next few years.

Luncheon

Saturday afternoon, I spoke at the Domestic Skills Symposium at Genesee County Village on the topic of the history of funeral food traditions. I started my talk by saying I felt this topic was fitting, because I had been grieving since Tuesday. And that I had watched my fellow mourner’s Instagram feeds fill up with photos of carby comfort food.

Have you turned to a particular food to nourish and comfort this week?

After my talk, there was a luncheon of mourning foods from the past and present, including funeral cakes flavored with caraway seed, sweet and lemony pan de muerte, stewed prunes–served in the Middle Ages, mostly for their dark color; there were Jell-o molds and Mormon funeral potatoes, and fried chicken. I stuffed myself.

Dinner

Lima beans with celery, onions and tomatoes.

Stuffed artichokes.

Bread. Coffee. Fruit.

By the evening, I was back on the road to drive to NYC. And I was back on my Italian diet. I made the mix of lima beans, celery onions and tomatoes in advance, gently sauteing them all together. I was bummed I didn’t have time make the recipe for stuffed artichokes, but here is a recipe from Gentile’s Italian cookbook:

STEWED ARTICHOKES

(Carciofi in stufato)

Wash the artichokes and cut the hard part of the leaves (the top). Widen the leaves and insert a hash composed of bread crumbs, parsely, salt, pepper and oil. Place the artichokes in the saucepan standing on their stalk, one touching the other. Cover them with water and let them cook for two hours or more. When the leaves are easily detached they are cooked.

I had a sweet roll and a plum with my dinner.