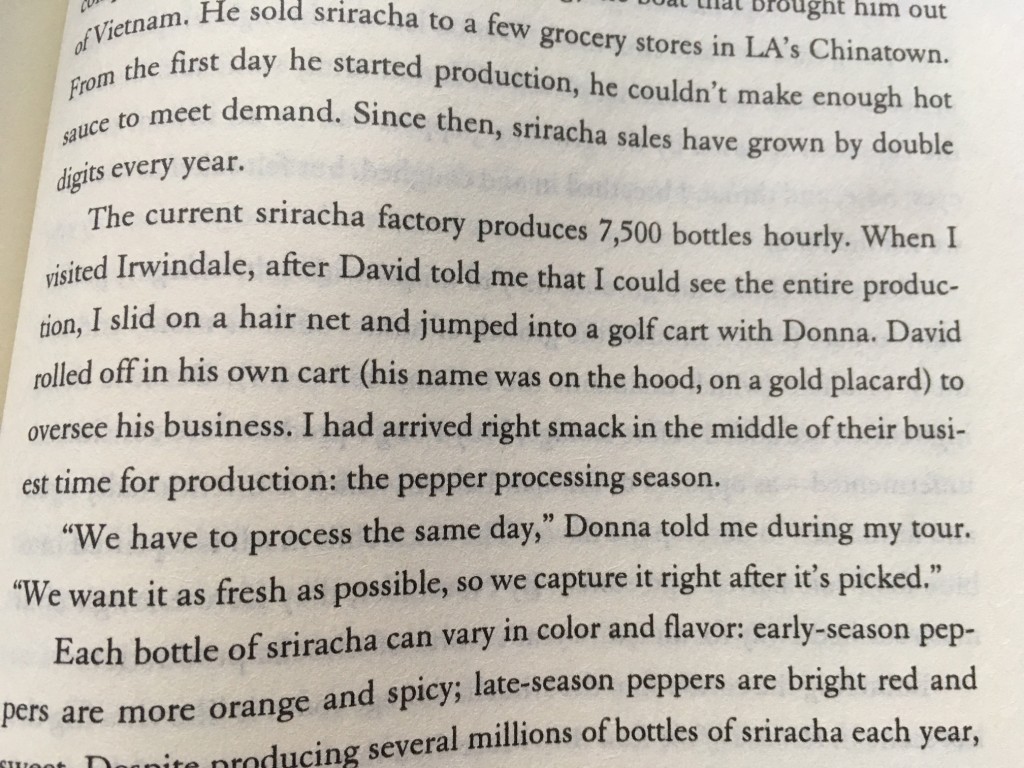

A roti quesadilla with a side of curry sauce and refried beans.

A roti quesadilla with a side of curry sauce and refried beans.

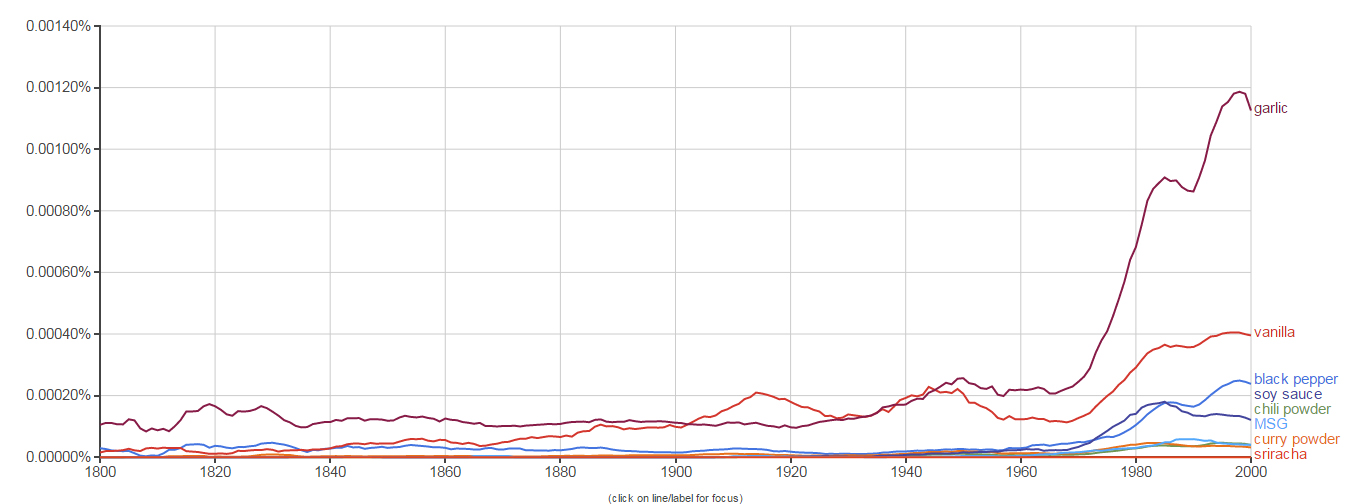

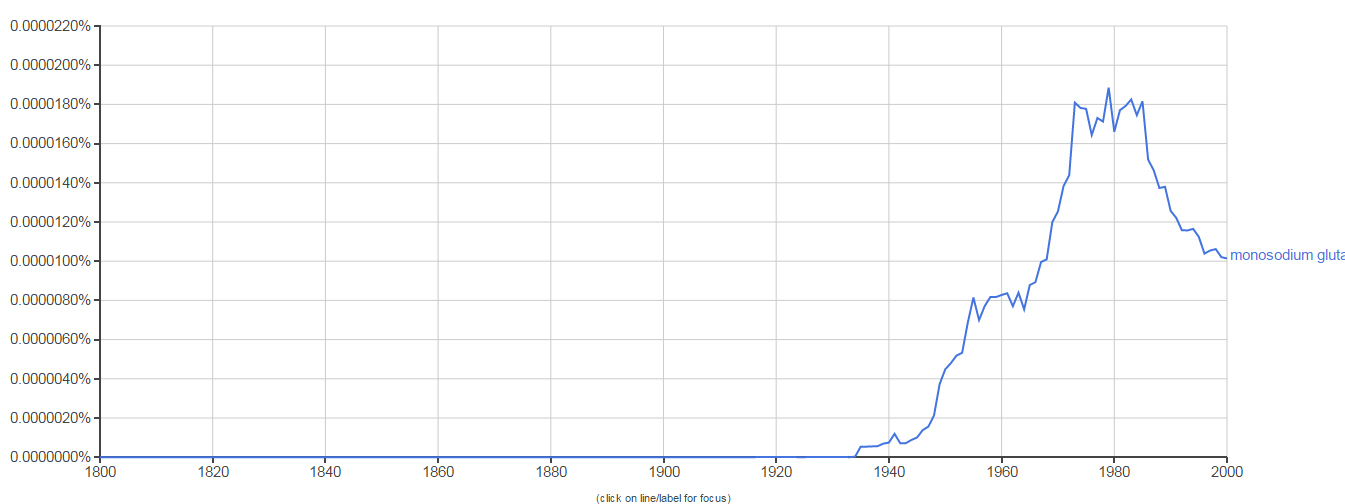

While writing my first book, Eight Flavors: The Untold Story of American Cuisine, I researched the eight most popular flavors in American cooking: black pepper, vanilla, chili powder, curry powder, soy sauce, garlic, MSG, and Sriracha. When I dived deep into each of these eight topics, I often found fascinating new information and recipes–some of which didn’t make it into the book–so I’ve decided to include it on my blog! If it whets your appetite to read the whole book, make sure to get your own copy here.

Out of all the flavors I included in my book, the one that puzzled Americans the most was the inclusion of curry. Most cooks I talked simply didn’t think of it as an American flavor. But Anglo-American women were cooking with curry as early as the 18th century, and early Indian immigrants were arriving as far back as the 1880s. The arrival of immigrants from India sparked a national debate about immigration, and restrictive immigration laws were eventually passed. But at the same time, a curious new culinary culture evolved: Punjabi-Mexican cuisine.

The Culture

By 1900, Muslims from Bengal were settling on the East Coast, and Punjabi Sikh immigrants were making a home on the West Coast. The Punjab is on India’s northwestern border, and was conquered by the British in 1848. Under the Raj, the Punjab was subject to land inheritance laws similar to Ireland in the same time period: the land was divided equally between all sons, as opposed to being inherited by the oldest son. This law resulted in farms too small to sustain a family. Debts drawn to support a living added to an increasingly dire situation. A family benefited by sending a husband or son to serve in the British military, or to find well-paying work in America. Many military men served in the British port of Hong Kong, a port of transit to America. News of work in the U.S. was passed along by returning countrymen, and encouraged other Sikhs to make the trip themselves.

The San Francisco Chronicle said of the first Sikh arrivals, who disembarked in 1899, “…The quartet formed the most picturesque group that has been seen on the Pacific mail dock for many a day…They are all fine looking men, Bakkshifed Singh in particular being a marvel of physical beauty. He stands 6 feet 2 inches and is built in proportion…All of them have been soldiers and policemen in China.”

They came to the West Coast to work in lumber yards and railroads; many of them were agricultural workers, migrating as the crops ripened. Cheap labor from Asia was integral to food production in California. These laborers aspired to own their own lands and farms.

Sikh immigration was a trickle, a novelty, until about 1910. In January, 1910, 97 “Hindoos” were admitted to the United States. The term was used to designate all immigrants of Indian origin, despite the fact these immigrants were Sikh. By April, 80-100 Indian Immigrants were entering the country every week. Between 1899 and 1914, nearly 7,000 Indians immigrated to California.

The local papers wailed about the “Hindu Horde” descending upon the country. Those that were anti-South Asian immigrant claimed that the incoming Indians were all …“racially unassimilable laborers who competed unfairly with white workers and sent their money home.” H.A. Millis, the superintendent of the U.S. Immigration Commission, said “..the Hindus are regarded as the least desirable, or, better the most undesirable, of all the eastern Asiatic races which have come to share our soil…

By 1917, a national law made South Asians officially excluded as a group. In reaction to increasing racial tensions on the West Coast, congress passed a law banning immigration from India. The act–known as the Asiatic Barred Zone–used degrees of latitude and longitude to slice out a portion of the world America didn’t want immigrants from, with India right smack in the middle. Special provisions were made for tourists and highly skilled workers like doctors. For the men who were already in California, they could stay; but would not be allowed to bring over their wives and children.

Prevented from marrying outside their “race” by California miscegenation laws, many Punjabi men married local Mexican women. The Mexican Revolution was pushing families to migrate across the border; many ended up working on cotton farms run by Sikh men. On their wedding certificates, both of their races were listed as “brown,” but sometimes they could be listed as black or white. As long as their skin tones were similar, they could be married; however, should one partner be considered “too white,” the marriage license would be denied. There were at least 378 of these unions, and as a result, a unique Mexican-Indian culture was created.

The Cuisine

The wives wanted to cook food to please their husbands; the husbands, as best they could, communicated what food they liked back home in India. Both cultures used similar spices in cooking, like cumin and chili; tortillas seemed like a sister to rotis, the Punjabi flatbread made from whole wheat flour.

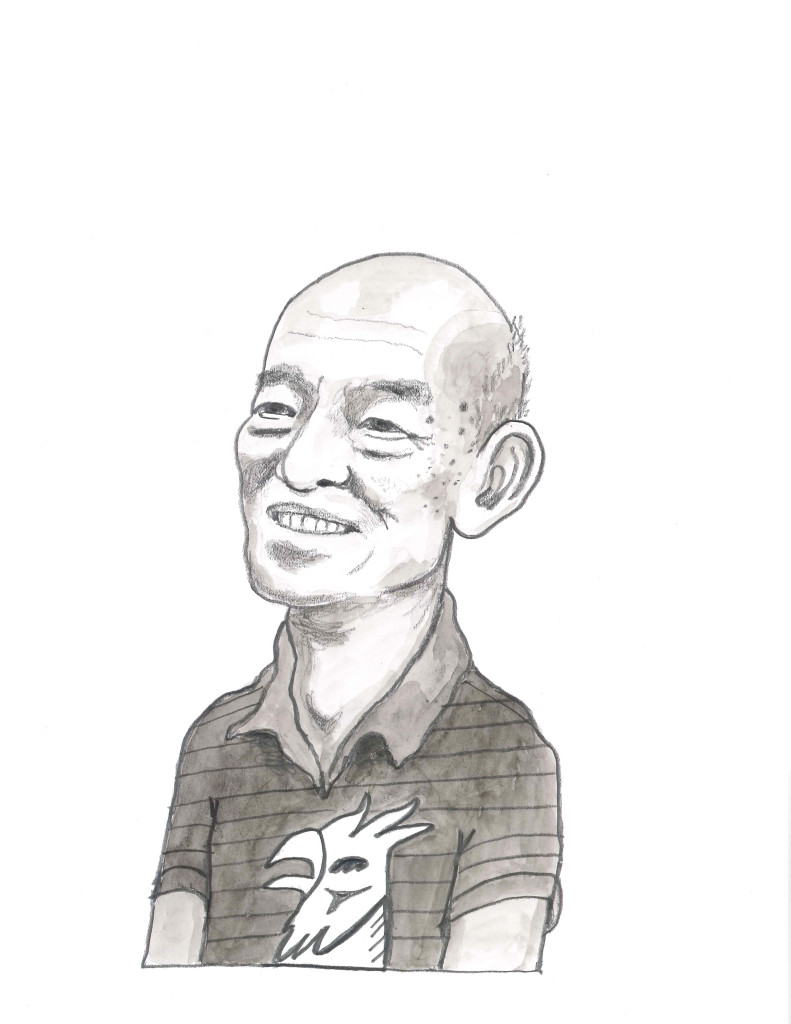

Moola Singh of Selma, California, married three times in his lifetime, to three different Mexican women: “I never have to explain anything India to my Mexican family,” Singh said. “Cooking the same, only talk us different…I went to Mexico two, three times, you know, not too far; just like India, just like it. Adobe houses in Mexico, they sit on floor there, make tortillas (roti you know). All kinds of food the same…” (source)

The two cuisines blended, not just in the home, but in the local restaurants. In Yuba City, California–which today has one of the world’s largest Sikh populations– El Ranchero was a Mexican restaurant serving Indian food, founded by the Rasul family. Tamara English, whose Indian grandfather and Mexican grandmother started the restaurant, remembers working there with her family:

“There for over 30 years we served Mexican food, along with curried chicken, lamb and roti. We were most famous for our Mex-Indian combo, the Roti Quesadilla, (the roti being Indian and the quesadilla of course being Mexican) which was most often served with a side of curry sauce for dipping…Just to round out the flavor I would add a side of refried beans to my plate.” (source)

The Recipe

Roti Quesadilla

Roti Quesadilla

You may have to head to an Indian specialty store to find roti, but I’ve also seen them in the frozen section of my local grocery store. I’d recommend a spicy curry sauce, which you can find in jars—the brand I used was “Patak’s.” After assembling this meal, I discovered nothing tastes as good as curry sauce over re-fried beans.

2 rotis

½ cup shredded cheese–cheddar, Monterey jack, or queso fresco

1 tablespoon butter

Curry sauce, for dipping

Re-fried beans

- Heat a small skillet—not much larger than your roti—on medium-low heat. Add butter.

- Once the butter has melted, place one roti in the skillet. Spread shredded cheese evenly over roti then top with second roti. Toast until the bottom roti begins to brown, then flip and continue to toast until cheese is melted.

- Cut into quarters and serve with beans and sauce.

Further Reading: Making Ethnic Choices: California’s Punjabi Mexican Americans

Julia Child.

Julia Child.