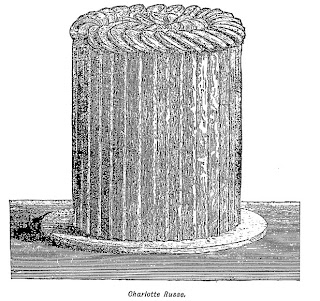

This very fine dessert is the second in my series of experiments with early chemical additives and my second attempt at a Charlotte Russe. Let’s kick off with the epic recipe I followed to make this thing:

***

A Very Fine Charlotte Russe

From The Lady’s Receipt Book by Eliza Leslie, 1847

***

***

I’m not going to provide you with a modern version of this recipe, because I discourage you from making it. It didn’t taste bad, but the effort just wasn’t worth it. However, I will walk you through the steps I took to recreate this “elegant” dessert.

First, I baked a cake. I googled around for an almong sponge cake recipe (thank you, Martha Stewart). I baked the cake in a glass bowl, so that it would begin to take the shape of a domed mold. When it came out of the oven, I hollowed out the middle and saved the resulting cake scraps. While still warm, I pressed the cake into a smaller bowl to create a deep well to recieve to all the very fine custard I was about to make.

I boiled one cup of whole milk with a vanilla bean and a few blades of mace. After about ten minutes, I removed the milk from the heat and plucked out the bean and mace, and whisked in one cup of heavy whipping cream. I set this mixture aside to cool. In the meantime, I beat three large eggs in an electric mixer until aerated and light in color. When the milk mixture was room temperature, I added the eggs in a slow drizzle, whisking constantly. I returned it to a medium heat on my stove top and cooked it for about ten minutes, stirring constantly. The resulting custard went into the refrigerator to cool.

In the meantime, I busted out my Isinglass, and dissolved it in a cup of boiling water. Here’s where things went a little wrong: I think the isinglass needed to be boiled in the water for a longer time. After it cooled, and I mixed it with my custard, it left tapioca-like beads in the pudding. It was an unpleasant texture that I think could have been avoided. Lesson leaned: cook that isinglass long and hard.

I added four tablespoons of sugar to the custard and isinglass mixture, and set it aside. I measured out a cup of white sugar into a bowl, and rubbed it on the skins of two lemons. This is a trick also used in punch making; it releases the flavorful oils contained in the lemon’s skin. I juiced the lemons and added the juice to the sugar, then added one cup sherry and half a cup brandy. I stirred the mixture until the sugar was dissolved. I added four cups of heavy whipping cream, and again used my mixer to beat the heck out of it. The resulting boozey whipped cream was folded into the custard, and this mixture went straight into my almond-cake-mold. I covered the bottom with the cake scraps I had set aside. I put it in the refrigerator to set.

An “icing made in the usual manner” meant a royal icing: a basic recipe of egg whites, powdered sugar, and egg whites. After about half an hour, the almond cake and custard was set. I flipped it out of the mold, iced it, and decorated it with fresh raspberries.

Jebus. This is a fussy recipe to say the least. The luxury of an electric mixer was an incredible time saver; note that to prepare this recipe in 1847 you had to make two meringues and one whipped cream BY HAND. Not to mention I had the modern conveince of a refrigerator to set the custard. The entire process still took me well over an hour to complete. The end result? Underwhelming. Edible, sweet, and boozy; but somehow not worth all the effort that went into it.

I think the point of this recipe was not the taste; but rather all the work that went into it. I find it hard to believe that the average housewife was preparing a Very Fine Charlotte Russe, even for the most special occasions. However, most middle and upper class households had servants. Time consuming and labor intensive, the job of the cook was the first to be relinquished by the lady of the house to hired help.

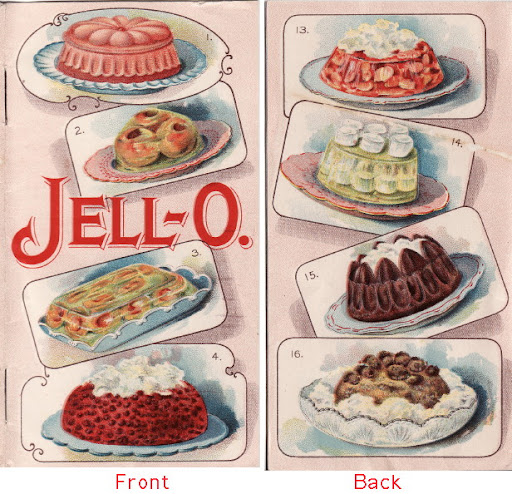

After the turn of the 20th century, when the servant trade began to fade, the lady of the house instead turned to new convenience foods. Canned, pre-packaged, and easy to prepare, she would use these products to cut down on cooking time, so she could use her day for other pursuits (and when I say she, I mean you and me).

So I believe a Very Fine Charlotte Russe was a recipe desgined to show off the skill of one’s servants and the wealth of one’s household. At any rate, stay away from it, unless you’ve got a few servants of your own.

I love the way Susan brings these recipes to life. Because they are handwritten, each recipe has its own individual character. They seem to speak about the woman who sat down and penned them 75 years ago or more.

I love the way Susan brings these recipes to life. Because they are handwritten, each recipe has its own individual character. They seem to speak about the woman who sat down and penned them 75 years ago or more.