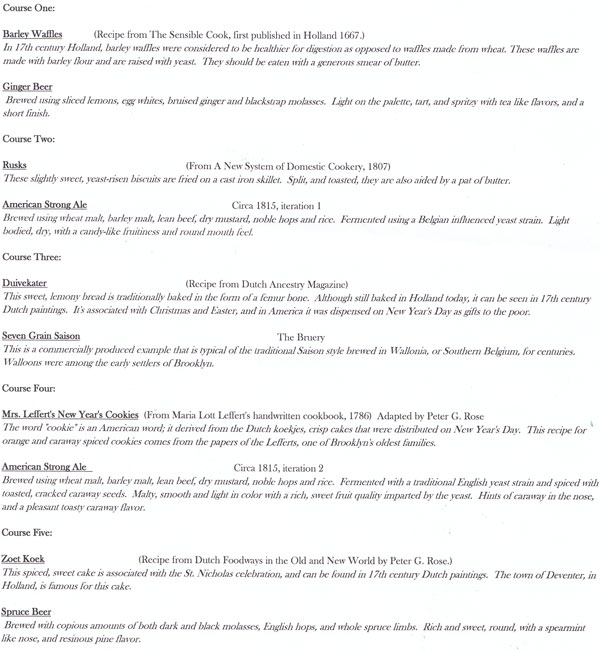

Baked pears, thickened buttermilk, and fried bread.

Baked pears, thickened buttermilk, and fried bread.

On Sunday, I appeared on the Heritage Radio Network, chatting with Carmen Devito & Alice Marcus Krieg of We Dig Plants. We talked all about PEARS! If you haven’t heard the show yet, go here and listen for free. I dug up some pear recipes from the annals of history with the idea that we would pick one to try. Well, we had a difficult time agreeing, so this week I’m going to cook up three very different 19th century pear recipes.

The first was Alice’s pick: Buttermilk soup or “Pop.” This recipe is odd. I’ve never seen a precedent for it: buttermilk is heated, mixed with pears, and poured over fried bread. Check it out:

I needed some buttermilk education, so I naturally turned to that font of knowledge, Wikipedia. I knew buttermilk as the bi-product of butter making: when cream is churned, the result is a solid (butter) and a liquid (buttermilk). I knew that before seperation, fresh milk was often set in a cellar to seperate into milk and cream; what I didn’t realize is that this milk would also ferment because of naturally occuring bacteria. This fermentation is what gives buttermilk its sour taste, although in modern production facilities we artificially inseminate pastuerized milk with a squirt of lactic acid bacteria.

Although the recipe doesn’t explicitly say to make a roux, I think it implies it. The roux will thicken the buttermilk.

****

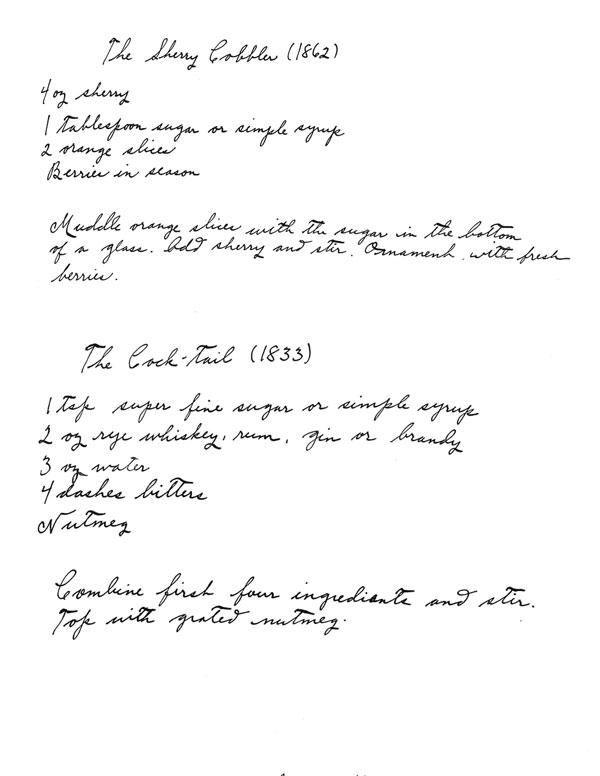

Buttermilk Soup or Pop

From Practical Sanitary and Economic Cooking by Mary Hinman Abel, 1890.

2 cups buttermilk

1 tablespoon flour

2 tablespoon butter

pinch salt

2 large pears (I used Bosc)

1/4 cup sugar (brown sugar would be good; maple syrup if you’re feeling adventurous)

1/2 tsp cinnamon (or spice of your choice)

1. Preheat oven to 350 degrees. Pare, core, and dice pears, then arrange in a baking tray (cake pan, etc). Sprinkle with sugar and spice. Bake for 35-45 minutes, or until tender.

2. In a large saucepan over a medium-low heat, heat 1 tablespoon of butter and the flour to make a roux. Cook until flour begins to brown. Add buttermilk and salt, turn heat to medium-high. Bring to a boil while stirring constantly, then turn heat off. Add baked pears to buttermilk mix, stir to combine.

3. Melt remaining butter in a small skillet and fry two slices of bread. Remove to a plate and top with pear/buttermilk mixture.

***

The original author of the recipe warns that cooking buttermilk “brings out the acid,” but I found the taste of the finished product to be surprisingly mild, either as a result of being cut by the fat of the butter or the sweetness of the pears. And frankly, I was skeptical of this recipe, and it was not my first pick to make. But I was delightfully wrong: this is the perfect snack. It’s like a delicious warm yogurt treat (tastes better than it sounds): the dairy was filling, the pears sweet, and when poured over hot, buttery bread, it’s just the right amount of food. Highly recommended, four stars, etc. etc. Try it.

On a completely unrelated note, I wrote this post jamming to my friend Gregg Gillis’ (Girl Talk) new album All Day, available for download for FREE. It is really, REALLY good.