Pearlash is powdery and slightly moist.

The History

If you were to scoop the ashes out of your fireplace and soak them in water, the resulting liquid would be full of lye. Lye can be used to make three things: soap, gun powder, or chemical leavener.

A “leavener” is a substance that gives baked goods their lightness. Today, we think nothing of adding a teaspoon of baking soda or baking powder to our cakes and cookies. But using chemicals to produce the carbon dioxide necessary to raise a cupcake is a relatively new idea.

Before chemicals, cooks would use yeast. Not just in bread, but yeast was often added into cake batter, along with a helpful dose of beer dregs or wine. The alternative was whipping eggs to add lightness, like in a sponge cake, although that particular recipe didn’t become popular until the end of the 19th century, after mechanized egg beaters were introduce.

Sometime in the 1780s an adventurous woman added potassium carbonate, or pearlash, to her dough. I’m ignorant as to how pearlash was produced historically, but the idea of using a lye-based chemical in cooking is an old one: everything from pretzels, to ramen, to hominy is processed with lye. Pearlash, combined with an acid like sour milk or citrus, produces a chemical reaction with a carbon dioxide by-product. Used in bakery batter, the result is little pockets of CO2 that makes baked goods textually light. Pearlash was only in use for a short time period, about 1780-1840. After that, Saleratus, which is chemically similar to baking soda, was introduced and more frequently used.

I was curious to try this product out and see if it actually worked. I ordered a couple of ounces from Deborah Peterson’s Pantry, the best place for all your 18th century cooking needs. I used it during my recent hearth cooking classes in a period appropriate recipe.

The Recipe

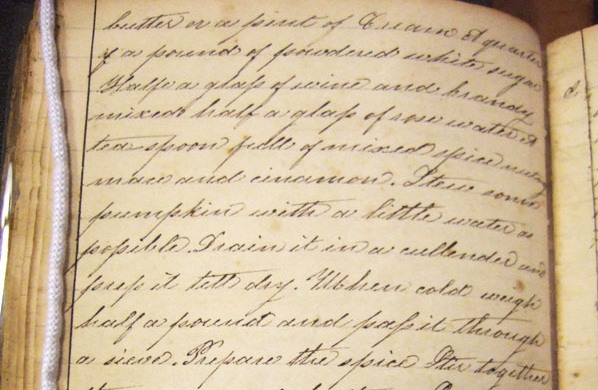

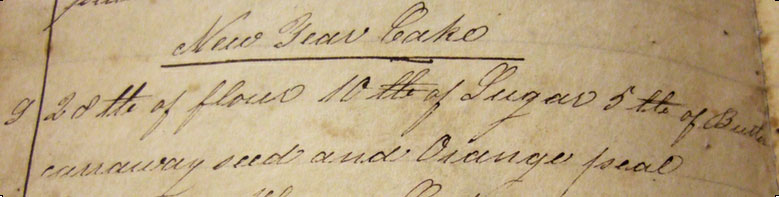

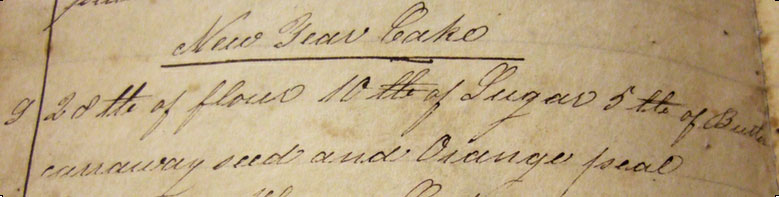

The recipe, for orange-caraway New Year’s Cakes, came from the cookbook-manuscript of Maria Lott Lefferts, a member of one of the founding families of Brooklyn. The use of pearlash, plus a recipe for “Ohio Cake,” serves to date this book to about 1820. It looks like this:

“New Year Cake

28 lbs of flour 10 lbs of Sugar 5 lbs of Butter

caraway seed and Orange peal”

This recipe doesn’t mention pearlash, but several of the other recipes in this book do. I checked the first cookbook printed in American, Amelia Simmon’s American Cookery, for an idea of how much pearlash to add. Here is the recipe I came up with:

New Years Cakes

Based on Marie Lott Leffert’s cookbook, c. 1820

1 cup light brown sugar, packed

1 stick salted butter

3 teaspoons pearlash dissolved in 1/2 cup milk

4 cups all purpose flour

Zest and juice of one orange

1 tsp ground caraway and 1 tsp whole caraway

Whisk together flour, zest and caraway. Beat butter and sugar until light and fluffy. Add orange juice and pearlash, then mix. Slowly add flour; mixing until flour is incorporated. Put in freezer one hour. Break off small pieces and roll very thin; cut with a cookie cutter or knife. Preheat oven to 300 degrees. Bake until cookies are slightly golden on the bottom, about 10 minutes.

***

Cookies leavened with pearlash come out of the oven.

Cookies leavened with pearlash come out of the oven.

The Results

I made the dough in advance and froze it, then dragged it to Brooklyn to be baked in a very period appropriately in a wood fire bake oven.

When the cookies came out of the oven, they had risen! They gained as much height, and as much textural lightness, as a modern cookie made with baking powder.

But how did they taste? The first bite contained the loveliness of orange and caraway (for a modern version of this recipe, I highly recommend using this recipe, and replacing the coriander with orange zest and caraway). But after swallowing, a horrible, alkaline bitterness filled my mouth. My body reacted accordingly: assuming that I had just been poisoned, I salivated uncontrollably.

At first, I wondered if I hadn’t used too much pearlash. But then something dawned on me: the earliest recipes to use pearlash were gingerbread recipes. Of the four recipes in Simmon’s cookbook, half of them were for gingerbread. A highly spiced gingerbread probably did a lot to hide the taste of the bitter base chemical.

And that’s why I like historic gastronomy. If I hadn’t actually baked with pearlash, and tasted it, I never would have made the gingerbread connection. There’s something to be said for living history.