Astoria Sourdough: highly recommended.

Astoria Sourdough: highly recommended.

Simple Sourdough Bread

1 cup starter

1 cup water

3 cups flour

2 tsp salt

2. “Dough is ready when its surface is dotted with bubbles. Lightly flour a work surface and place dough on it; sprinkle it with a little more flour and fold it over on itself…” (reference video for this technique)

3. Carefully pick up the dough, and drop into the preheated pot. Cover with lid and bake 20 minutes, then remove lid and bake another 15 to 30 minutes, “until loaf is beautifully browned. Cool on a rack.”

***

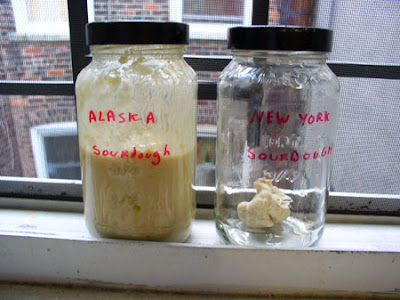

When I busted out my Astoria (nee New York) Sourdough Starter and gave it a sniff, the smell had definitely mellowed from stinky cheese to almost imperceptibly sour. After scooping out a cup of starter for my dough, I added a cup of flour and 3/4 water back into the starter, mixed it up, and let it sit out for about 6 hours before I put it back into the fridge. Use distilled or bottled water; tap water could be chlorinated and will kill your yeast friends.

I prepared the bread according to the recipe above, starting with the Astoria starter. The loaf came out of the oven a little weird looking: shiny, burnt in places, and lopsided. The latter is the fault of my oven, which, like my floor, slopes to the center of the room. Despite its suspicious looks, the bread smelled delicious. Like Parmesan cheese.

I really should have let the bread cool, but I was excited, and my roommate talked me into slicing it open. It was incredibly dense, and I deduced that I had not let it rise long enough.

We tasted it anyway: it was wonderful. Like a Parmesan cheese bread, that occasionally also tasted like baked macaroni and cheese. It was delicious. I could have eaten it all day. I was amazed. I had literally created this bread from nothing. How can so much flavor come from a mason jar full of flour and water on my windowsill? After having to throw away so many starters to get here, the whole thing just seemed like magic.

“I made this from the air,” I pointed out to my roommate. “You’re eating a piece of New York City. Literally.”

I put the Alaskan sourdough into the oven next; it rose slightly better, and the result was slightly less dense. But nowhere near as flavorful as the Astoria Sourdough. The New York bread was hands down our favorite.

I put the Alaskan sourdough into the oven next; it rose slightly better, and the result was slightly less dense. But nowhere near as flavorful as the Astoria Sourdough. The New York bread was hands down our favorite.

Both loaves came out too dense. I don’t think I let either loaf of bread rise long enough: I hit closer to the 8 hour mark instead of 12. Bittman even recommends letting the dough rise for another 2 hours after you pull it out of the bowl and fold it over, which may be worth a try. Bittman also suggests cooking at 450 for 30 minutes with the lid on, the 15-30 minutes with the lid off. I am going to try his cooking temperature next time, to see if it prevents burnt bits.

The flavor of Sourdough bread varies by the region in which it is baked: sourdough was baked in San Francisco and Alaska because itinerant men needed to start their own yeast cultures; the sourdough from these regions became famous because of the particularly tasty local strains of yeast. New York yeast apparently tastes like mac and cheese.

I declare this experiment a success, although the technique will need to be tweaked. I will definitely be baking another loaf of delicious, cheesy, Astoria Sourdough. And I feel much closer to being able to survive on the frontier, just like so many other women had to do, long ago. Next week: I learn how to slaughter a buffalo.(just kidding)

(or maybe not…)

P.S.: For a little more science behind sourdough, here’s Alton Brown: