We only have room for 50 participants, so please RSVP on Facebook (or leave a comment on this post) to reserve a spot!

Cocktail Hour: The Whiskey Sour

Illustration by Angela Oster.

Illustration by Angela Oster.

Whiskey is my drink of choice, so I admit I love the unintentional whiskey theme of this week.

The Whiskey Sour was invented sometime in the middle of the 19th century; Jerry Thomas describes a brandy and a gin variation in his 1862 book. Other variations: a dash of egg white makes it into the Boston Sour, and Boston also gave birth to the Ward 8 in 1898, which adds orange juice and grenadine.

***

The Whiskey Sour

From The Cocktail Book: A Sideboard Manual for Gentlemen, 1926

2 teaspoons simple syrup (or super fine sugar)

2-3 dashes lemon juice

1 tablespoon seltzer

2 ounces whiskey

1. In a rocks glass, add simple syrup, lemon juice and seltzer. Stir to combine (or until sugar is dissolved).

2. Fill glass with ice, and add whiskey. Stir until the outside of the glass is cold. Garnish with a cherry and orange wedge, or seasonal fruits.

***

And if you like a Whiskey Sour, try the Ward III at the 19th C. Pub Crawl’s last stop, Ward III: “Made with bourbon, strawberries, egg whites and nutmeg, it’s actually ‘a derivation of the classic Sour,’ explains (owner) Neff. A historical classic, viewed through rose-colored glasses—and given a healthy dose of red berries, too.” (Metromix New York)

For a full list of Ward III’s “exquisite libations”, go here.

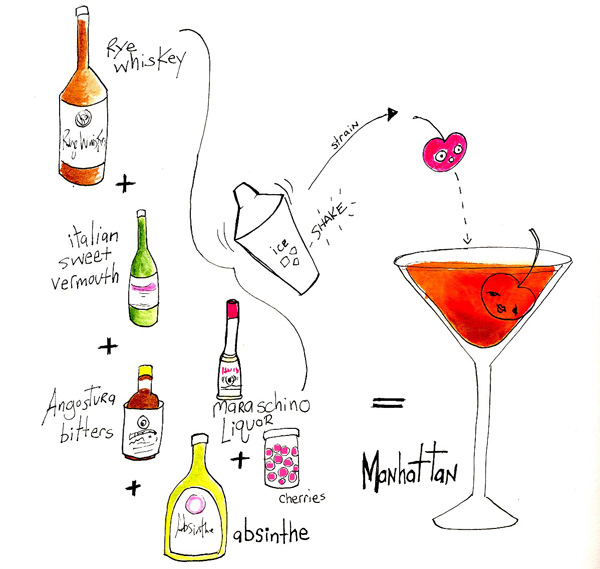

Cocktail Hour: The Manhattan

Illustration by Angela Oster.

David Wondrich, cocktail historian and Jerry Thomas expert, says the Manhattan “…Probably dates to the Manhattan Club, which was a social club for rich Democrats at Fifth Avenue and 15th Street in the 1870s.” Accustomed to the maraschino cherry standards of a modern-day Manhattan, I was pleasantly surprised when I was recently served a variation from Wondrich’s book Imbibe! Remarkably smooth and even a touch sweet, this has been my favorite drink I’ve quaffed in a long time.

***

The Manhattan

From Imbibe! By David Wondrich, 2007.

Based on a recipe by Jerry Thomas.

2 ounces rye whiskey

1 ounce Italian sweet vermouth

1 dash Angostura bitters

1 dash Absinthe

1 barspoon (or one teaspoon) Maraschino liquor

1. Fill a tumbler with ice; add all ingredients and stir until the outside of the glass is cold.

2. Strain into a martini (cocktail) glass, and garnish with a cherry or a twist of lemon peel.

***

Ready for another variation of this classic drink? Try Madame X‘s Dirty Cherry Manhattan. The second stop on the 19th C. Pub Crawl, Madam X serves up a Manhattan made with Basil Hayden’s 8-year-old bourbon, sour cherry syrup and sweet vermouth. For a full list of Madame X’s cocktails, go here.

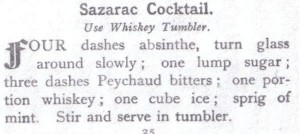

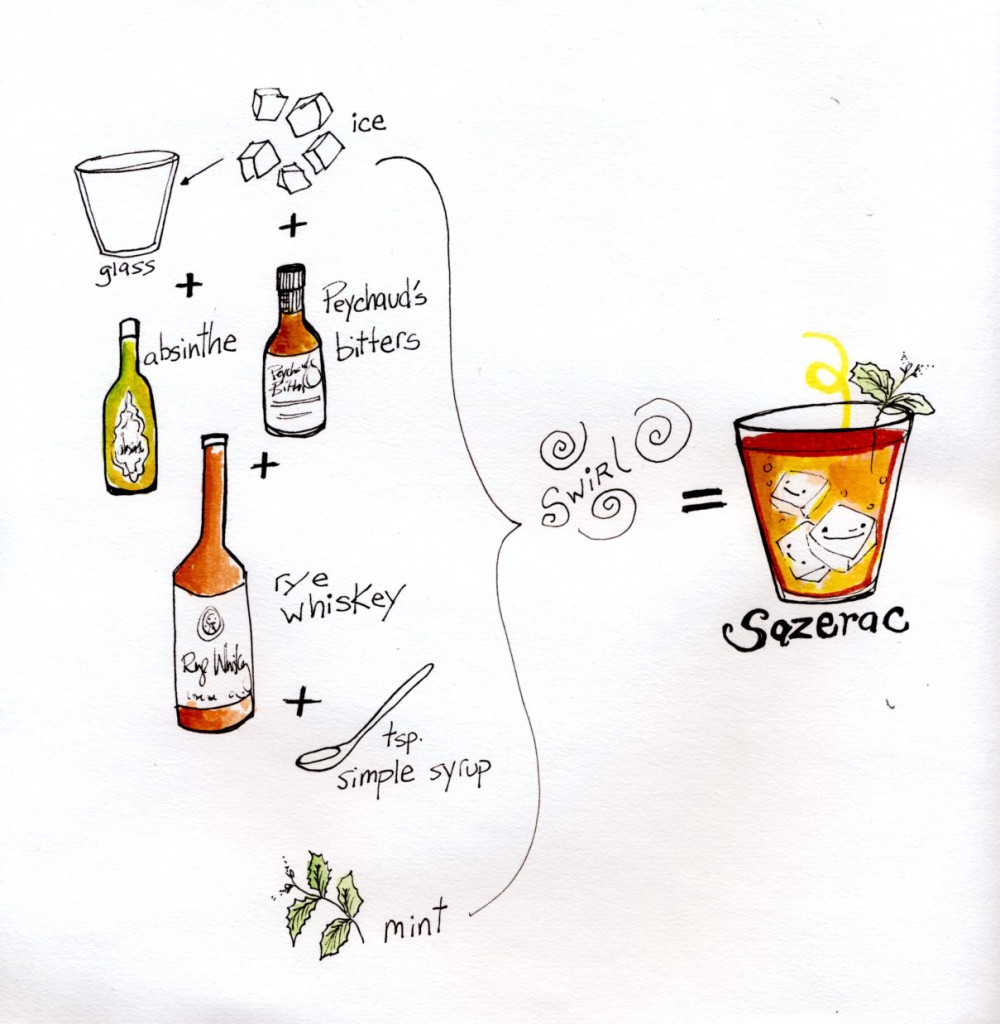

Cocktail Hour: The Sazerac

Illustration by Angela Oster.

Illustration by Angela Oster.

When Absinthe became legal in the states, the first drink cocktail enthusiasts began mixing up was the Sazerac. Invented in New Orleans circa 1870, it’s based on an even older Cognas drink invented by Antoine Amédée Peychaud; his bitters are indispensable in creating this cocktail.

***

The Sazerac

From The Cocktail Book 1926 Reprint: A Sideboard Manual For Gentlemen, 1926

four dashes absinthe

2 ounces rye whiskey

3 dashed Peychaud bitters

1 teaspoon simple syrup

Mint

1. Pour absinthe into a rocks glass, and swirl it around until the bottom and the sides of the glass are coated. Pour out absinthe.

2. Add ice, then whiskey, bitters, and simple syrup. Still until the outside of the glass is cold. Garnish with a sprig of mint and enjoy.

***

For an updated version of this recipe, order the 17th Street Sazerac at Rye House, the first stop on the 19th Century Pub Crawl on Saturday. Metromix New York, who inspired this post, had this to say about the modernized cocktail: “Made from Rittenhouse Rye, Hine Cognac, demerara syrup, Peychaud and Angostura bitters and Marteau Absinthe, the drink has all the anise zip of the original, but a deeper tone as well. Not a traditional 1835 pour by any means.”

Sounds ok to me, but I may be more tempted by the Rye House Punch, a combination of chai infused Rittenhouse rye, Batavia Arrack, lemon, grapefruit, Angostura bitters, and soda. Not only do I love a good chai tea, but I am fascinated with Batavia Arrack, a popular 19th century spirit only recently re-introduced to the market. I’m going to pick up a bottle to experiment with some 19th-century recipes, but I can’t wait to try it in a Victorian-inspired cocktail on Saturday.

For a full list of Ryehouse’s cocktails, go here.

Cocktail Hour: Cocktail Week!

Image from How To Mix Drinks by Jerry Thomas

When the weather gets all warm and luscious like this, all I want to do is drink. I want to sit under a tree and sip a frosty cocktail. So, to lead up to Saturday’s 19th C. Pub Crawl, I’m declaring it Cocktail Week. Everyday, I’ll be posting the recipe for an iconic 19th-century cocktail and featuring a pub crawl bar that serves up their own version of a classic concoction.

Let’s get ready to imbibe.

Events: The New York 19th C. Pub Crawl

The New York 19th C. Pub Crawl

Starting at 5:30pm

Meet at Ryehouse 11 W. 17th St. (between 5th and 6th Ave.)

New York, NY

Free, but drinks are additional. RSVP via Facebook to reserve a spot.

Join us for night of nineteenth-century debauchery at several of New York City’s oldest bars and most notorious dens of vice! We will meet promptly at 5:30 p.m. at Ryehouse (11 West 17th Street), a new bar that revives and reinvents the classic cocktail. From there, we’ll head to Madame X, The Ear Inn, Onieal’s Grand Street and (should we still posses the fortitude and sobriety) Ward 3.

The perfect outing for cocktail enthusiasts and history lovers alike–come sip drinks in some of New York’s most historic pubs and bars dedicated to the revival of classic drinks.

Appropriate nineteenth century attire is encouraged, but by no means required. Visit www.19thcpubcrawl.com for the most up-to-date information including exclusive drink specials.

See you there!

History Dish Mondays: A Cake Bakes in Queens

Puff Cake, a la Mrs. Osborn.

Puff Cake, a la Mrs. Osborn.

Today is a very special HDM, because I am collaborating with the lovely Susan LaRosa of a Cake Bakes in Brookyln. Susan focuses on early 20thcentury cakes and she plans to make several hundred of them from handwritten recipes reclaimed from flea markets in Ohio.

I love the way Susan brings these recipes to life. Because they are handwritten, each recipe has its own individual character. They seem to speak about the woman who sat down and penned them 75 years ago or more.

I love the way Susan brings these recipes to life. Because they are handwritten, each recipe has its own individual character. They seem to speak about the woman who sat down and penned them 75 years ago or more.

Susan and I decided to trade, and bake cakes from each other’s collections. I loaned her a cookbook published in the 1880s which has pages of handwritten cake recipes attached in the back (like “Altogether Cake“). Susan gave me a stack of her own materials to pick from, but I knew right away which one I wanted: Mrs. Osborn’s Cakes of Quality.

The book is brittle and crumbling; the pages within are individually typed and simply bound. The book was sent to housewives across the country who wrote in and requested Mrs. Osborn’s advice. Who was she? We don’t really know. Her writing seems to indicate she was a woman left without means who turned to baking to support herself. Susan calls her the “Patron Saint of Cakes,” and wrote this post about what she knows about Mrs. O and what she’s trying to find out about this mystery woman.

The introduction to Mrs. O’s book declares: “If you follow my directions, you simply cannot fail. You’ll earn the admiration–perhaps the envy, in some cases–of your neighbors. None of them will be able to make cake which will equal yours.” Her writing has an air of letting you in on a great secret–and Mrs. Osborn’s cake making techniques are wildly different. She has you put the cake into a cold oven– a cold oven!! Mrs. Osborn suggests: “Try Puff Cake first. This is a fine cake and very easy to make. This will acquaint you with my system and then you will be ready to make Angel, Klondike, and the others.” Who was I to disagree? Puff Cake it is.

***

Puff Cake

From Mrs. Osborne’s Cakes of Quality, by Mrs. Grace Osborne, 1919.

I have a confession: despite my mother constantly admonishing my sloppy measurements as a child, I’ve grown into a sloppy baker. Baking does take a certain understanding of chemistry, yes; but not until watching Top Chef did I realize outsiders saw it as a secret alchemical art form. I find baking as easy as cooking: it allows for some improvisation and (thankfully) there is some margin for mistakes.

But Mrs. Osborn threatened me to “…Do exactly as I tell you,” and I did. I sifted and sifted and leveled my measuring cup with a knife—a practice I’ve not kept up since leaving the watching eye of my mother. The cake mixed well, but I was nervous about trying Mrs. O’s baking techniques. I have no idea how she monitored her baking temperature so exactly– even using a thermometer. It seems like it would be an hour and a quarter of constant fussing to get the temperature just right. I decided to bump my temperature up at the end of each 15 minutes and see what happened.

I ended up pulling the cake out of the oven fifteen minutes early. After it cooled, I cut it and saw it had gotten a little dark on the bottom–not burned, just browned. My roommate and I tried a slice: “Tastes like cake,” he said. It was exactly what I had been thinking.

The cake was very fluffy from the beaten egg whites and had a butteryness that angel food cakes lack. The browned bottom tasted oddly like a pretzel at first; then, the next day, it tasted downright bitter. The cake will be disposed of.

Although I’ve had a bit of a disaster with Mrs. O’s baking methods, I’m still tempted to try another cake from her book. But at the moment, I’m not inspiring any cake-envy.

Cocktail Hour: The Mint Julep — Irresistible!

It is the KENTUCKY DERBY today, and you know what that means!! Mint Julep season is kicking off, and in my mind, that means summer has arrived! Oh, how I love a mint julep!!

The below quotation is from a Captain Marryatt, a “gallant” English seaman with a penchant for the “nectareous drink” we Americans call a julep. The Captain’s adulation of this cocktail was reprinted in How to Mix Drinks by Jerry Thomas (1862),

“I must descant a little upon the mint julep, as it is with the thermometer at 100 one of the most delightful and insinuating potations that ever was invented and may be drunk with equal satisfaction when the thermometer is as low as 70… I learned how to make them and succeeded pretty well: Put into a tumbler about a dozen sprigs of the tender shoots of mint upon them put a spoonful of white sugar and equal proportions of peach and common brandy so as to fill it up one third or perhaps a little less. Then take rasped or pounded ice and fill up the tumbler… As the ice melts, you drink. I once overheard two ladies talking in the next room to me, and one of them said ‘Well if I have a weakness for any one thing it is for a mint julep!’– a very amiable weakness and proving her good sense and good taste. They are in fact, like the American ladies, irresistible “

***

Captain Marryatt’s American Mint Julep

Adapted from How to Mix Drinks by Jerry Thomas (1862)

1 heaping teaspoon superfine sugar

1 teaspoon water

5-6 sprigs of mint

1.5 ounces Cognac (whiskey can be substituted here with equally pleasing results)

1.5 ounces Peach Brandy

Place mint, sugar and water in the bottom of a julep cup or rocks glass. Muddle until the flavor of the mint has been released. Fill up glass with crushed or shaved ice, then add alcohol. Stir vigorously until the outside of the glass is foggy with condensation and cold to the touch. Enjoy.

This julep is my Derby standby. Allow yourself the pleasure of the addition of Peach Brandy (or a teaspoon of peach bitters) to your everyday Julep routine. You won’t regret it.

***

Jerry Thomas’s Mint Julep

How to Mix Drinks by Jerry Thomas (1862)

This is Thomas’s rather decadent first entry in the “Julep” chapter of his book.

1 heaping teaspoon superfine sugar

1 teaspoon water

10-12 sprigs of mint

1 ounce Cognac

1/5 ounce Dark Rum

Orange slices and berries

Place half the mint mint, sugar and water in the bottom of a julep cup or rocks glass. Muddle until the flavor of the mint has been released. Fill up glass with crushed or shaved ice, then add Cognac. Stir vigorously until the outside of the glass is foggy with condensation and cold to the touch. Use you stir or spoon to pull out the mint springs; insert fresh sprigs into the ice with their stems downward. Arrange berries and orange slices within this mint bouquet, pour the rum over top, and sprinkle with sugar.

***

This was the first time I’ve tried Thomas’s julep recipe: Drunk through a straw, the cocktail is actually pretty amazing, albeit a little over the top. The straw is necessary, so you don’t whack yourself in the face with mint every time you take a sip. The liquor is sweet and very, very minty. I think I’ve been skimping on the mint in my juleps: one should pack that glass full for the best flavor. The fruit on top, drizzled in rum and sprinkled with sugar, is also special treat.

But one needn’t be so extravagant in their julep enjoyment. Don’t just savor a Julep this Saturday, but sip them all season long. Remember: the Mint Julep is the drink of the summer!

History Dish Mondays: A Very Fine Charlotte Russe

This very fine dessert is the second in my series of experiments with early chemical additives and my second attempt at a Charlotte Russe. Let’s kick off with the epic recipe I followed to make this thing:

***

A Very Fine Charlotte Russe

From The Lady’s Receipt Book by Eliza Leslie, 1847

I’m not going to provide you with a modern version of this recipe, because I discourage you from making it. It didn’t taste bad, but the effort just wasn’t worth it. However, I will walk you through the steps I took to recreate this “elegant” dessert.

First, I baked a cake. I googled around for an almong sponge cake recipe (thank you, Martha Stewart). I baked the cake in a glass bowl, so that it would begin to take the shape of a domed mold. When it came out of the oven, I hollowed out the middle and saved the resulting cake scraps. While still warm, I pressed the cake into a smaller bowl to create a deep well to recieve to all the very fine custard I was about to make.

I boiled one cup of whole milk with a vanilla bean and a few blades of mace. After about ten minutes, I removed the milk from the heat and plucked out the bean and mace, and whisked in one cup of heavy whipping cream. I set this mixture aside to cool. In the meantime, I beat three large eggs in an electric mixer until aerated and light in color. When the milk mixture was room temperature, I added the eggs in a slow drizzle, whisking constantly. I returned it to a medium heat on my stove top and cooked it for about ten minutes, stirring constantly. The resulting custard went into the refrigerator to cool.

In the meantime, I busted out my Isinglass, and dissolved it in a cup of boiling water. Here’s where things went a little wrong: I think the isinglass needed to be boiled in the water for a longer time. After it cooled, and I mixed it with my custard, it left tapioca-like beads in the pudding. It was an unpleasant texture that I think could have been avoided. Lesson leaned: cook that isinglass long and hard.

I added four tablespoons of sugar to the custard and isinglass mixture, and set it aside. I measured out a cup of white sugar into a bowl, and rubbed it on the skins of two lemons. This is a trick also used in punch making; it releases the flavorful oils contained in the lemon’s skin. I juiced the lemons and added the juice to the sugar, then added one cup sherry and half a cup brandy. I stirred the mixture until the sugar was dissolved. I added four cups of heavy whipping cream, and again used my mixer to beat the heck out of it. The resulting boozey whipped cream was folded into the custard, and this mixture went straight into my almond-cake-mold. I covered the bottom with the cake scraps I had set aside. I put it in the refrigerator to set.

An “icing made in the usual manner” meant a royal icing: a basic recipe of egg whites, powdered sugar, and egg whites. After about half an hour, the almond cake and custard was set. I flipped it out of the mold, iced it, and decorated it with fresh raspberries.

Jebus. This is a fussy recipe to say the least. The luxury of an electric mixer was an incredible time saver; note that to prepare this recipe in 1847 you had to make two meringues and one whipped cream BY HAND. Not to mention I had the modern conveince of a refrigerator to set the custard. The entire process still took me well over an hour to complete. The end result? Underwhelming. Edible, sweet, and boozy; but somehow not worth all the effort that went into it.

I think the point of this recipe was not the taste; but rather all the work that went into it. I find it hard to believe that the average housewife was preparing a Very Fine Charlotte Russe, even for the most special occasions. However, most middle and upper class households had servants. Time consuming and labor intensive, the job of the cook was the first to be relinquished by the lady of the house to hired help.

After the turn of the 20th century, when the servant trade began to fade, the lady of the house instead turned to new convenience foods. Canned, pre-packaged, and easy to prepare, she would use these products to cut down on cooking time, so she could use her day for other pursuits (and when I say she, I mean you and me).

So I believe a Very Fine Charlotte Russe was a recipe desgined to show off the skill of one’s servants and the wealth of one’s household. At any rate, stay away from it, unless you’ve got a few servants of your own.

Video: Me on Japanese TV!

I was recently featured in a Japanese TV show about New York culture called “New York Wave.” We shot for five days: we ate some bear and we ate some turtle; we cooked 19th century pancakes on an open hearth; we had so many adventures. All in Japanese. It was one of the most intense experiences of my life.

Enjoy.