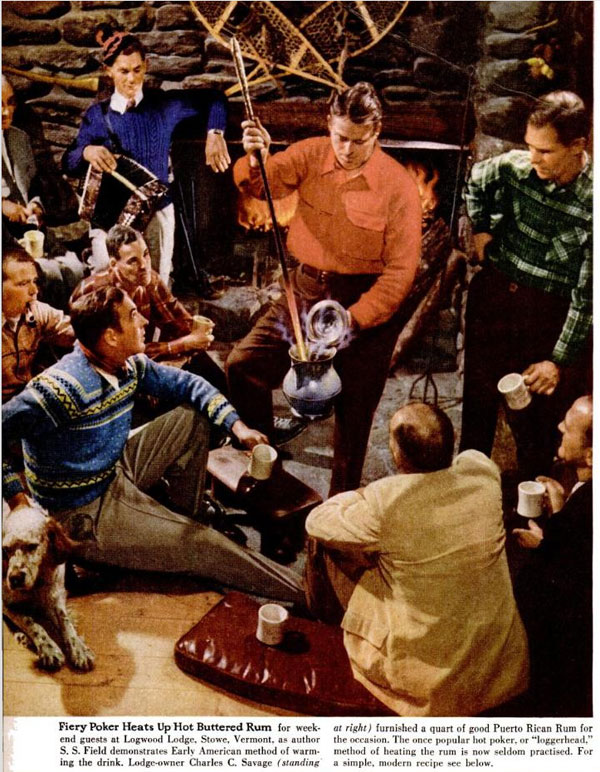

Waiting for callers on New Year’s Day. (source)

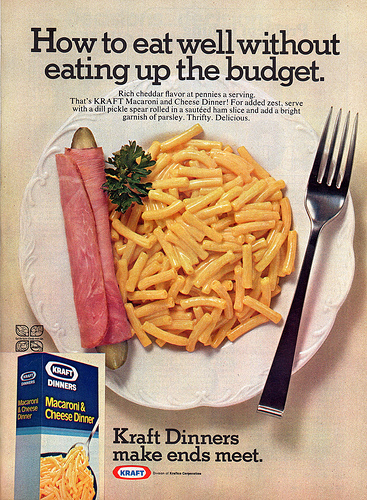

19th century New Yorkers didn’t do their drinking on New Year’s Eve; instead, New Year’s Day was the day for revelry, in what the Merchant’s House Museum recently described as “an elegant, albeit thinly masked, pub crawl.”

On New Years Day, it was tradition to travel all around New York and visit the houses of your friends and family. This was an old Dutch tradition brought to New Amsterdam that was revived in New York in the 19th century, and celebrated by the entire city, not just Dutch immigrants and their descendants. This custom was known as “calling,” and some people would visit between 30-100 houses in a day.

It was usually the men who would travel from house to house, while the women stayed at home to meet the guests–and they might see 200-300 friends and family in a day. The days leading up to the occasion were particularly busy, as houses were cleaned top to bottom, sometimes refurnished, and there was a general slew of “baking, brewing, stewing, broiling, and frying” according to Lights and Shadows of New York Life – or, the Sights and Sensations of the Great City, a fascinating, often sensationalized, encyclopedia on the city from 1872.

According to Lights and Shadows, women would have a new dress made, and would rely on hairdressers–or “artist of hair”–who would visit their homes. But because the season was so busy, hairdressers would often have to work through the night, calling on the women at three or four in the morning. The ladies would spent the rest of the night sleeping sitting up, or in some other Geisha-like sleeping arrangement, so they didn’t muss their do.

Punchmakers were another set employed throughout the night–but I’ve written about them before, and you can read about them here.

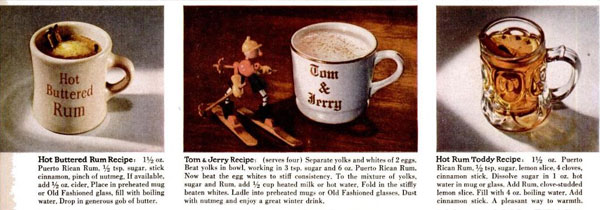

A punch bowl in the collection of the William H. Seward House.

A punch bowl in the collection of the William H. Seward House.

When the great day arrived, the whole city was already in motion by 9am. If you’ve been doing this a number of years, you knew enough to make a bee-line for the houses with the best food. Sometimes, as you ran into your friends on the street, you would exchange inside information about who has the best plumb pudding or charlotte russe this year.

A typical visit would consist of giving the greetings of the season, accepting refreshments and then moving on to the next house. The men would keep a list, and check off names or each family they visited. The list was a necessity, for as the day rolled on, you’d accept a drink at every house. According to Lights and Shadows

“At the outset, of course, everything is conducted with the utmost propriety, but, as the day wears on, the generous liquors they have imbibed begin to ‘tell’ upon the callers…Towards the close of the day, everything is in confusion–the door-bell is never silent. Crowds of young men, in various stages of intoxication, rush into the lighted parlous, leer at the hostess in the vain effort to offer their respects, call for liquor drink it, and stagger out, to repeat the scene at some other house…Strange as it may seem, it is no disgrace to get drunk on New Year’s Day.”

I’ve always loved this tradition and have often sought to recreate it. After the hubbub of the holidays, I can’t imagine anything more lovely that calling on all of my friends, and having a few quiet hours to enjoy their company. I intended to make my rounds today, but after following the normal 21st century pattern of revelry, I woke up with a hangover so nasty that I haven’t done much of anything today. I will leave in about an hour, to see two friends I haven’t got a chance to talk to since Thanksgiving, and to cut their silhouettes for their belated Christmas present. I don’t think I’ll be drinking any punch, though.

Updated 11pm: My visit was wonderful! Will (originally of Manchester, England) and Sarah (of Kentucky!) presented my fiancee and I with a cheese platter, hot milky tea, and a real English Christmas pudding! They doused it in brandy and set it ablaze. It was the most perfect New Year’s visit.

***

You can read Lights and Shadows of New York Life here, or purchase it here

I’d also recommend The Battle for Christmas, a wonderful book on the development on the holiday season in America. The author focuses a lot on New York life and tells some great stories about visiting on New Year’s Day.

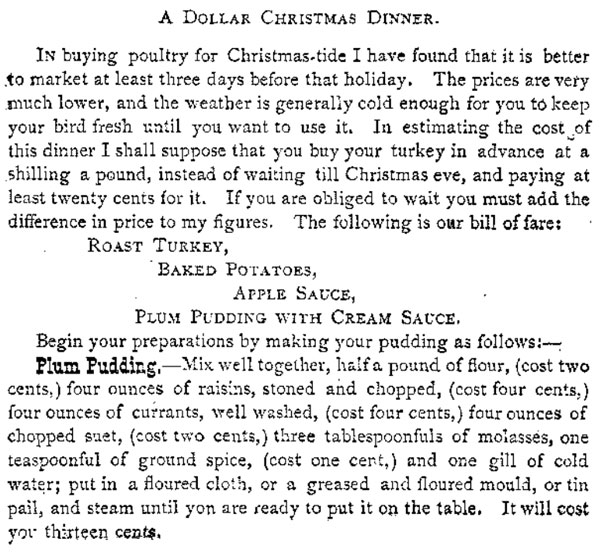

Buch de Noel from a tree trunk cake mold.

Buch de Noel from a tree trunk cake mold.

CORNELIA VAN VARICK’S HOLIDAY KITCHEN

CORNELIA VAN VARICK’S HOLIDAY KITCHEN