A better sweet potato casserole, with fancy lemon-citron marshmallows.

A better sweet potato casserole, with fancy lemon-citron marshmallows.

Sweet Potato Casserole topped with warm, melty marshmallows is a Thanksgiving classic. But whenever I eat it, I find myself thinking “Why is this so awful? Who wants all the flavorless sweet glop next to their turkey?” Recently, I’ve been making savory, roast sweet potatoes instead of a casserole. But I thought perhaps by looking in to the origins of this dish, I might be able to retronovate a better modern casserole. Let’s see if it works!

The History

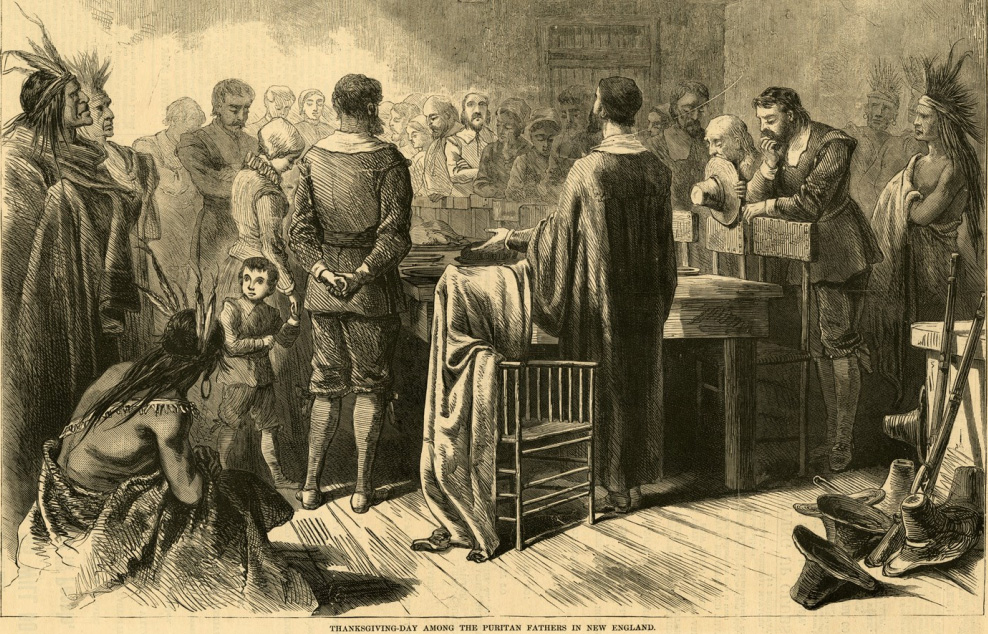

Sweet potatoes are a new world tuber, although they weren’t present at the Original Thanksgiving. Native to Central and South America, they were introduced to the North via colonists from Europe. Columbus is credited was transporting them home to the Old World (although he seems to be mis-credited with a lot of stuff) and by the 16th century they appeared in a British herbal encyclopedia, which recommends serving them “roasted and infused with wine, boiled with prunes, or roasted with oil, vinegar, and salt.” (source) Yum/Nom.

Sweet Potato in the 1597 Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes

Sweet Potato in the 1597 Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes

Historians suspect that this recipe for “potatoe pudding” is actually a sweet potato pudding recipe. It appears in the first America cookbook published in 1796, and we have definite sweet potato recipe examples by the 1830s, which would indicate they were pretty entrenched in American culture by that time. So let’s skip ahead to the marshmallows.

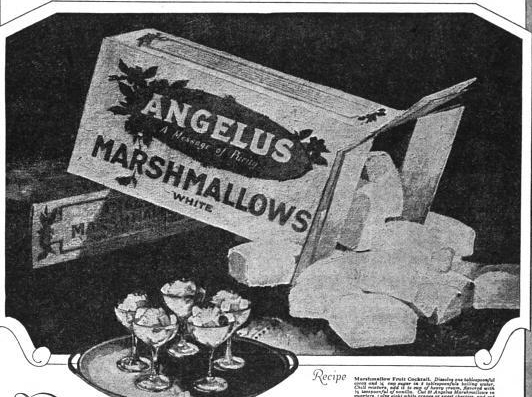

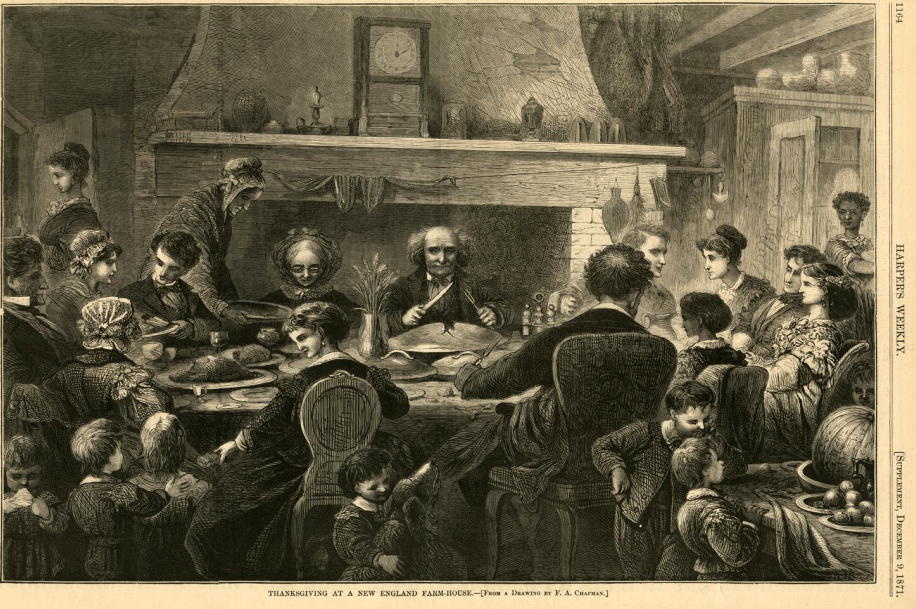

Marshmallows were very trendy at the turn of the 20th century. Formerly an expensive, handmade treat, machines had been invented to automate the process. Using marshmallows in one’s kitchen was considered very modern, as well as labor saving: housewives were encouraged to substitute them for meringue and whipped cream, two very laborious toppings. (source)

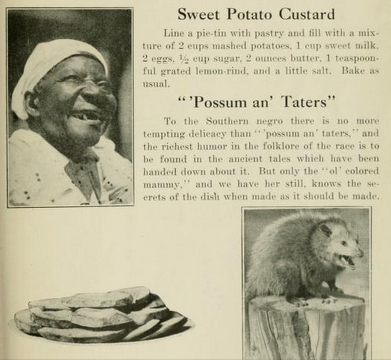

The first recipe to top candied sweet potatoes with marshmallows allegedly comes from a 1917 Angelus Marshmallow recipe booklet, but I haven’t been able to lay my hands on a copy to verify that claim. The earliest recipe I’ve seen comes from a 1918 trade journal called Sweet Potatoes and Yams. It’s filled with growing and storage tips for tubers, as well as casual racism.

WTF???

WTF???

Let’s digress for a moment: imagine a world where racism is so embedded in the culture, that it was considered acceptable, if not hilarious, to include an image that compares a black woman to a possum in a trade journal about sweet potatoes. I debated not sharing this image, but I don’t believe in whitewashing history. Things sucked then; be glad for now, and always work towards a better future.

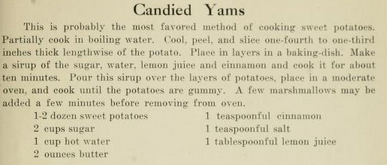

Just above the racist image/text is a recipe for candied yams with marshmallows:

I thought that the addition of lemon juice to the sweet potatoes might be a huge improvement. By adding acid, it would break up all the sweet on sweet action I normally get in sweet potato casserole. Then, after researching turn of the century marshmallows, I had another revelation:

Square marshmallows? From 1920.

Square marshmallows? From 1920.

Notice that the marshmallows in this 1920 ad are not the keg-shaped, dried out things we normally see in the grocery store. They more closely resemble what I would call “gourmet” marshmallows, that tend to have a moister texture and richer flavor. I realized that improving the quality of the marshmallows would greatly improve the quality of the dish.

You can buy gourmet marshmallows online, in bakeries, and you can make them yourself

. I wandered around Whole Foods trying to find a suitable product, and stumbled across these “fancy” Lemon-Citron flavored marshmallows, imported from France.

Found only where the finest marshmallows are sold.

Found only where the finest marshmallows are sold.

The Recipe

Sweet potatoes from a farm in upstate New York.

Sweet potatoes from a farm in upstate New York.

Improved Sweet Potato Casserole with Marshmallows

Adapted from Sweet Potatoes and Yams, 1918

1 dozen medium sweet potatoes (more or less, depending on size)

2 cups light brown sugar

1 cup water

2 teaspoons cinnamon

1 lemon, juiced

2 tablespoons unsalted butter

2 teaspoons salt

Fancy Marshmallows (of whatever brand/style/flavor of your choosing. Cinnamon, Yuzu

, or Bourbon

flavor have potential for this recipe) )

1. There are two ways your can prepare your sweet potatoes: You can wrap them in foil and bake them whole for 1 hour at 400 degrees before slicing them; this preparation method will give you a softer texture for the final dish. Or, you can do like I did: simply slice the potatoes thin and add them to the casserole; this method results in a firmer texture. You can also choose to leave the skins on or peel them.

2. In a medium saucepan, combine sugar, water, cinnamon, lemon juice, and butter. Place over high heat until sugar is dissolved. Stir, then pour over potatoes in casserole dish.

3. Sprinkle potatoes with salt.

4. If you pre-baked the potatoes, bake 30 minutes at 350 degrees. If you just sliced them, bake 2 hours at 375 degrees. In the last five minutes of cooking, scatter marshmallows over surface of the potatoes and turn temperature up to broil. Keep a careful eye on them so they brown, but don’t burn. Cool on a rack.

The Results

I thought the Lemon-Citron will pair well with the lemon juice in the casserole, and the short story is that it did. The whole recipe is probably the best sweet potato casserole I have ever had, blending the perfect amounts of spice, citrus, and caramelized sugar. Give it a whirl, experiment more, and I promise you it will be a great improvement to your Thanksgiving table.

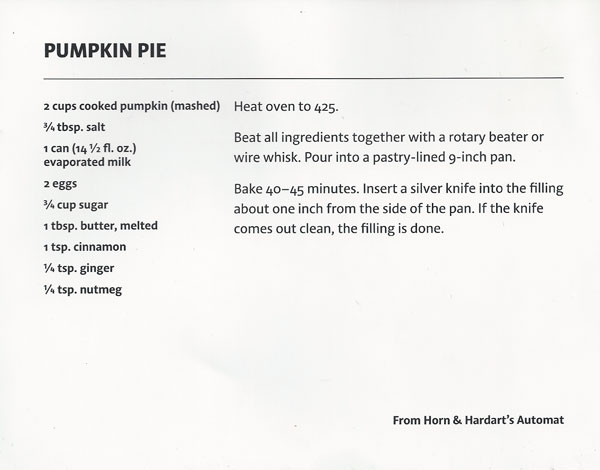

Horn and Hardart’s automat, from

Horn and Hardart’s automat, from

Left: What a centerpiece! From Betty Crocker’s Party Book, 1960.

Left: What a centerpiece! From Betty Crocker’s Party Book, 1960.