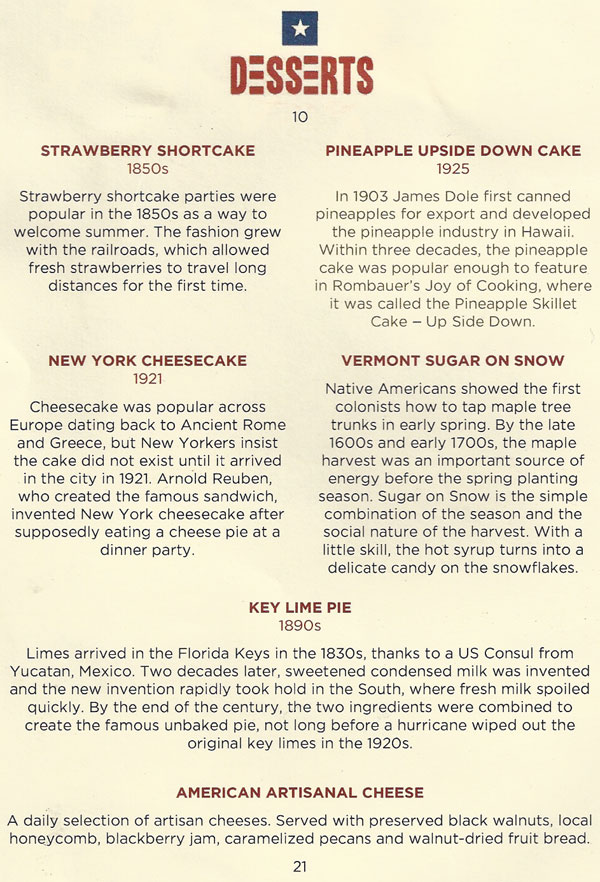

A flight of pulque. Clockwise from the top: oatmeal, guava, lime, celery, mango, and plain in the center.

A flight of pulque. Clockwise from the top: oatmeal, guava, lime, celery, mango, and plain in the center.

We were way too old to be in this place. We were definitely the creepy old couple. Looking around the bar, most of the people drinking around us looked to be in their early twenties, and perhaps younger: the drinking age in Mexico is 18, after all. And more than that, there was a youthful rebelliousness in this crowd seldom seen Mexico City: in general mild temperatures and Catholicism resulted in conservative dress. But in the pulqueria, facial piercings were the norm, women bared their shoulders, and one crusty punkette asked if we would like to buy a pot brownie (brownie de cannabis).

My husband and I were recently married (late in life, by some standards, at the ages of 30 and 31) and honeymooning in Mexico City, when curiosity led us to a Pulqueria. Pulque is an ancient drink made from the fermented sap of the agave; it is thought to have been developed at least 2,000 years ago. Distill that juice, and you get tequila (or mezcal); ferment it like beer, and you get pulque, thick and milky white. A staple of Aztec life, for many years it survived as a drink of the working class; but recently, pulque has been receiving press for its growing popularity amongst Mexico City’s youth.

A 1,000 year old mural depicted people drinking pulque. (source)

A 1,000 year old mural depicted people drinking pulque. (source)

The Pulqueria La Risa, where we sat, has been pouring the thick beverage for over a century. In the modern incarnation of this drink, fruit juices, or nuts and grains along with sugar are added. On the day we visited, the sabores de dia included Guava, Mango, Celery, Blackberry, Oatmeal, and Pine Nut. In its pure state, I found pulque to taste like stomach acid, so the addition of sweet fruit juice is a huge improvement. The result is something like a wine cooler: sweet in flavor, but with an ABV on level with a beer.

Inside Pulqueria La Risa.

Inside Pulqueria La Risa.

I think it’s wine cooler-like qualities are responsible for its resurgence amongst the young. The drink is even beginning to make its way to New York City; Pulqueria, in lower Manhattan, offers ginger-peach and tomatillo pulques alongside a full Mexcian menu. A glass of pulque costs $14, about ten times the going price in Mexico city.

Do I think pulque will be a huge hit north of the border? Not likely. After carving out a small corner in the densely packed bar, my husband and I ordered a pitcher of oatmeal pulque. Sweetened and topped with cinnamon, its the breakfast that gets you drunk. We had planned to order several pitchers, and perhaps a discrete, foam, to-go cup, and get slowly drunk on a hot afternoon. But after the first pitcher, our stomachs were full and grossly distended. Pulque is often known as a meal in a glass, packed full of calories and vitamins, and is incredibly filling. We left, sober and gassy, and fairly confident that that was the first, and last time, we’d try to get drunk on pulque.

I was in Washington DC last weekend and toured the

I was in Washington DC last weekend and toured the