A 1960s cheese fondue. You want it.

A 1960s cheese fondue. You want it.

The end of an era is coming, both for the characters of Mad Men and for those of us who have followed the show. If you’re planning a last episode party, may I suggest fondue, from a cookbook owned by Betty Draper herself.

The History

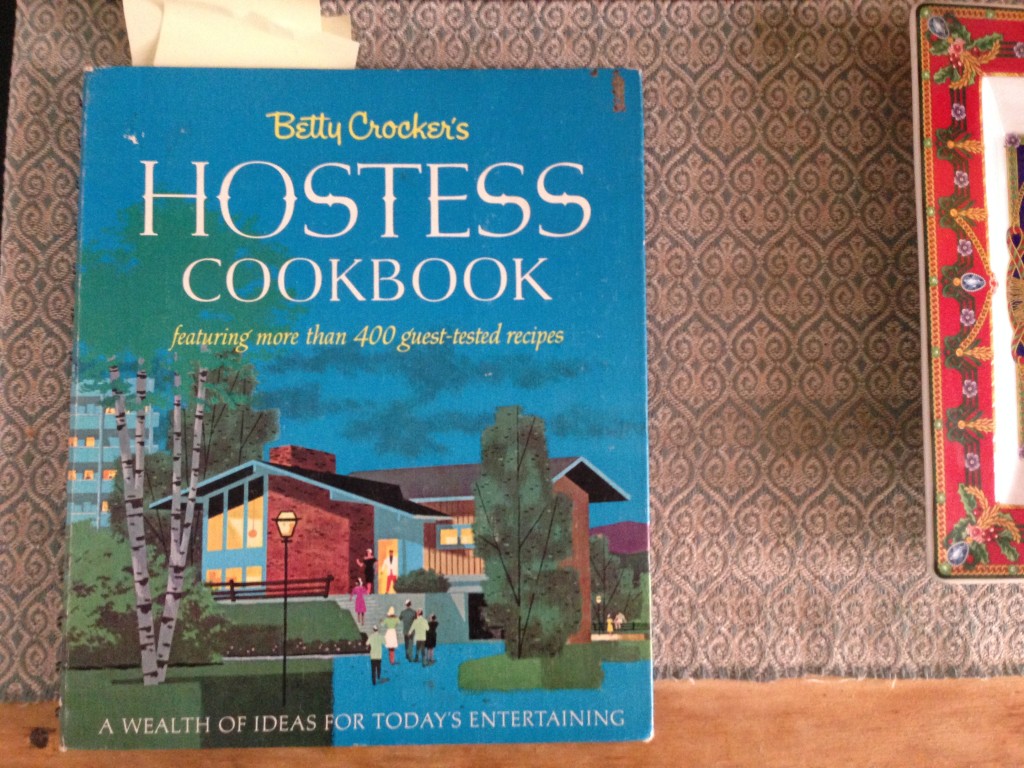

Back in the early seasons, when Betty was still Mrs. Draper, I noticed a cookbook on her counter:

You can see this set right now at the Museum of the Moving Image in Queens, btw.

You can see this set right now at the Museum of the Moving Image in Queens, btw.

Betty Crocker’s Hostess Cookbook.

Betty Crocker’s Hostess Cookbook.

Much like Betty Draper, Betty Crocker is fictional, a creation of the Washburn Crosby Company, which would eventually become General Mills. “She” answered letters written to the company by housewives with baking questions. The first cookbook under her name was published in 1950, and was so popular “…sales rivaled those of the Bible.” (source)

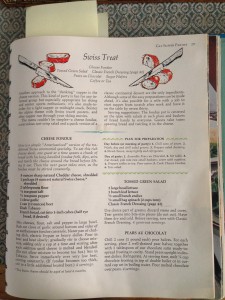

Betty Crocker’s Hostess Cookbook offered “A Wealth of Ideas for Today’s Entertaining.” Paging through the book, I came across a menu for a fondue party, entitled “Swiss Treat.”

“The menu couldn’t be simpler,” Ms. Crocker enthuses. “A cheese fondue, a marvelous tart-crisp salad, and a quick version of a classic continental dessert (pears au chocolat) are the only ingredients…It’s also possible for a wife with a job to start supper after work and have it on the table by seven thirty.” How progressive–even Joan could whip this one up!

According to David Sax, author of The Tastemakers: Why We’re Crazy for Cupcakes but Fed Up with Fondue, fondue started in late 19th century Switzerland as a cheap and filling meal of melted cheese and stale bread. It became a staple of tavern culture, and was most well-known in Neuchâtel, where fondue was a mixture of emmenthal and gruyere cheese, garlic, pepper, nutmeg, white wine and kirsch. It was popular among groups of young people, and games were invented: if a girl lost their bread in the pot, they had to kiss the first boy to their left. Fondue came stateside when it was served at the Chalet Swiss restaurant in New York, becoming particularly popular by the 1950s.

By the 1960s, fondue is suggested for entertaining in the home in books like Betty Crocker’s. Fondue sets were popular wedding gifts,and a fondue party considered a convivial gathering. Sax makes the interesting connection between these communal eating parties and the sexual liberation of the 1960s:

“It is no coincidence that the fondue trend rose in concert with the budding sexual revolution in North America. The hotpot gatherings involved inherent physical and social contact, even in their most G-rated form…Fondue could not work with inhibitions–there were not individual portions, no fondue for one–it was a meal of forced intimacy…With enough wine and kirsch, a fondue party was the perfect setting to really get to know the Franklins from down the block, if you know what I mean.”

The Recipes

Click for larger images.

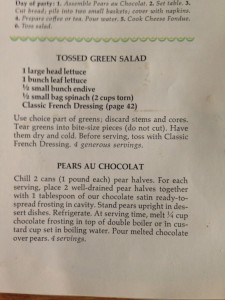

I prepared the salad and dressing in advance. The composition of the salad really delighted me: whereas I was expecting just iceberg lettuce, I got a colorful and flavorful mix of leaf lettuce, endive (I substituted radicchio because my store didn’t have endive!) and spinach. I laughed that the “Classic French Dressing” included a 1/4 teaspoon of MSG, which I absolutely added, along with 1/4 cup olive oil, 2 tablespoons sherry vinegar, 3/4 teaspoon salt, 1 crushed clove garlic, and 1/4 teaspoon fresh ground pepper.

I assembled the pears next: they were simply chilled canned pears with chocolate frosting gobbed in the middle and melted over top. They were the most disappointing dish of the evening.

Pears au Chocolat, just before serving.

Pears au Chocolat, just before serving.

And last the cheese: I borrowed a fondue kit from a friend. Ask around! I’m sure you know someone that has one and vintage versions can be got for cheap in every second hand store in the country. I lit a sterno can under the vat and added a bottle of a hoppy IPA. As the beer heated, I slowly stirred in grated cheese, a handful at a time. In about 20 minutes, the cheese was steamy, smooth and ready to be eaten with torn chunks of baguette and pumpernickel rye.

The Results

While we waited for the cheese to heat, I served salads. The dressing was phenomenal, thanks to the satisfying umami of the added MSG. It had a nice garlic flavor, too, despite only having one crushed clove of garlic. Salad, over all, got nods of approval and a solid A+.

I was skeptical of the cheese because of the recipe’s simplicity: mostly beer and cheese. But it turned out tangy and hoppy; rich, but not overwhelming. Some thought the flavor paired best with the pumpernickel, but I liked it on the baguette. Underplates were a must to catch dripping strings of luscious cheese. The fondue recipe was just enough to feed four hungry people.

Hoisting a giant, cheese-soaked hunk of bread in the air, a party guest declared: “If someone put that in their mouth, it would be like the most sexual thing ever!”

After dinner, we didn’t serve coffee or tea, but lots of wine and eventually whiskey. Although the conversation got interesting, no one “got to know the Franklins,” if you know what I mean.

At the end of the night, we were stuffed with hot cheese and satisfied. My guests shared recipes their families made from the Betty Crocker cookbooks. Preparing this menu, I expected lackluster mid-century food; but on the contrary, it seems that Crocker’s cookbooks were popular because the recipes were basic but delicious.