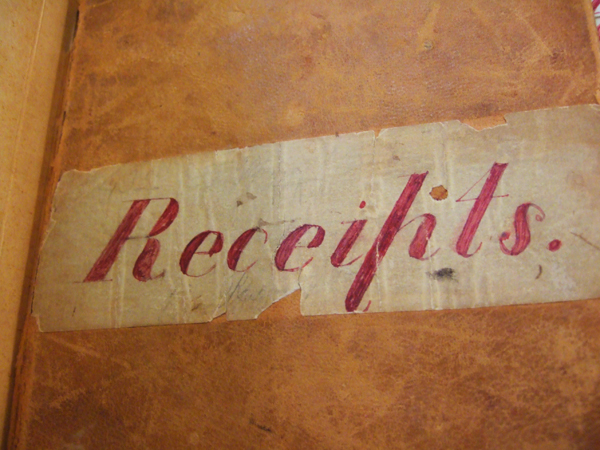

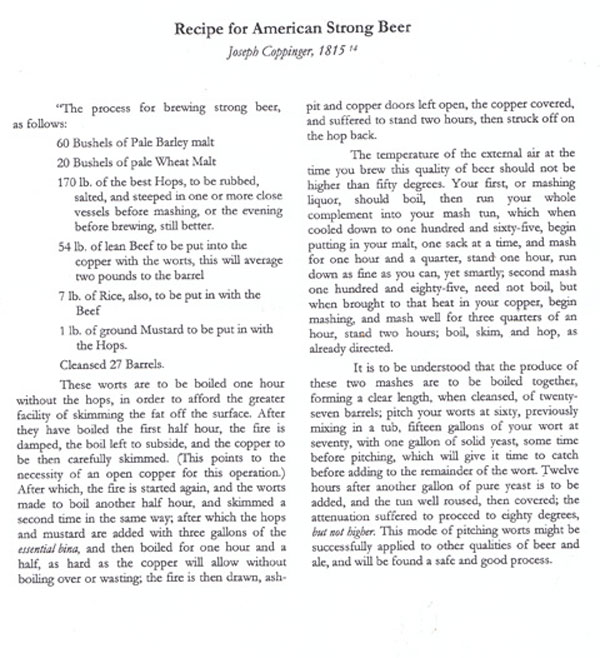

The front cover of Mrs. Maria Sneckner-Lintz’s Receipt book, from the NYHS archives.

This post is the first in a series of three celebrating the re-opening of the New York Historical Society. We’re going to focus on examples from the NYHS’s culinary holdings.

Today, we’re looking at a beautiful manuscript from 19th century New York; beautiful both for its physical appearance, and for the important information it gives us about daily life in the city 100 years ago.

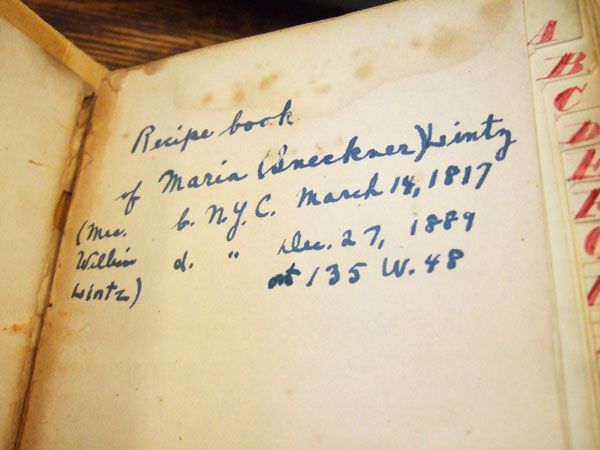

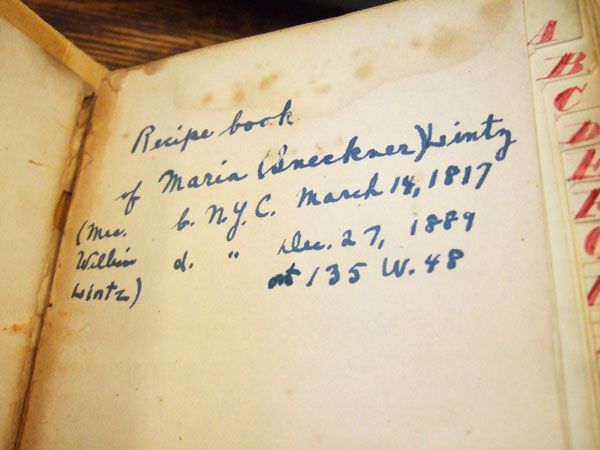

The book is written by Mrs. Wilbur Lintz (nee Maria Sneckner), who was born in 1817 and passed in 1889. During her life, she decided to record her favorite recipes and culinary knowledge. Overall, this book gives us a peek into what was being cooked in a middle-class, New York kitchen.

“Recipe book of Maria (Sneckner) Lintz (Mrs. Wilbur Lintz) b. N.Y.C. March 14, 1817 d. ” Dec 27, 1889 at 135 w. 48″

Mrs. Lintz was a very organized woman; her cookbook is alphabetically indexed in a way that allowed her to add to her recipes over time.

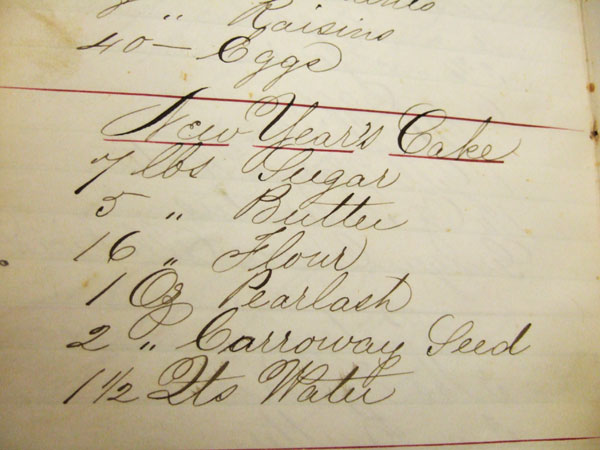

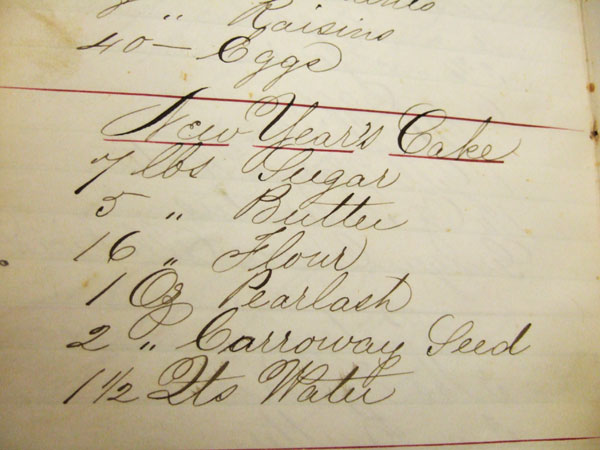

Sneckner is an old Dutch name, and in that line, the manuscript features several traditional New Amsterdam-style recipes. The recipe book includes three different recipes for New York Cakes, a cookie flavored with caraway. In the Dutch tradition, these cakes were passed out to visitors on New Year’s Day; the practice of visiting on New Year’s was revived by the upper and middle classes of New York in the middle of the 19th century.

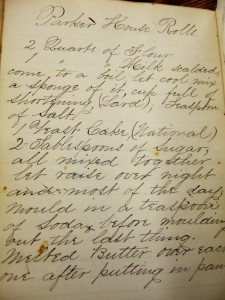

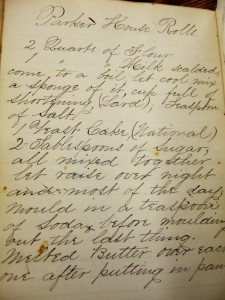

Additionally, this manuscript features recipes at the height of their fashion and modernity, like this one, at left, for Parker House Rolls.

These rolls were invented in the Parker House Hotel of Boston in the 1870s and quickly became very fashionable. “They are made by folding a butter-brushed round of dough in half; when baked, the roll has a pleasing abundance of crusty surface. Recipes for Parker House rolls first appeared in cookbooks during the 1880s.” (Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America, 2004)

Parker House Rolls.–One quart of cold boiled milk, two quarts of flour. Make a hole in the middle of the flour, take one half cup of yeast, one half cup of sugar, add the milk, and pour into the flour, with a little salt; let it stand as it is until morning, then knead hard, and let it rise. Knead again at four o’clock in the afternoon, cut out ready to bake, and let them rise again. Bake twenty minutes.–Mass. Ploughman.

—“Parker House Rolls,” New Hampshire Sentinel, April 9, 1874 (p. 1) (sourced from The Food Timeline)

The Parker House still exists, and still serves its famous rolls, as well as its other great creation, The Boston Cream Pie.

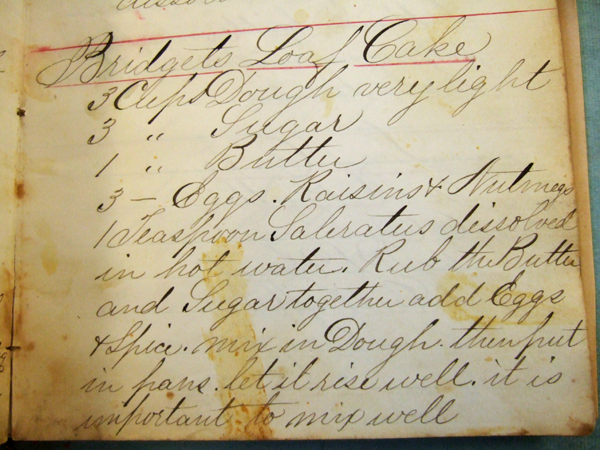

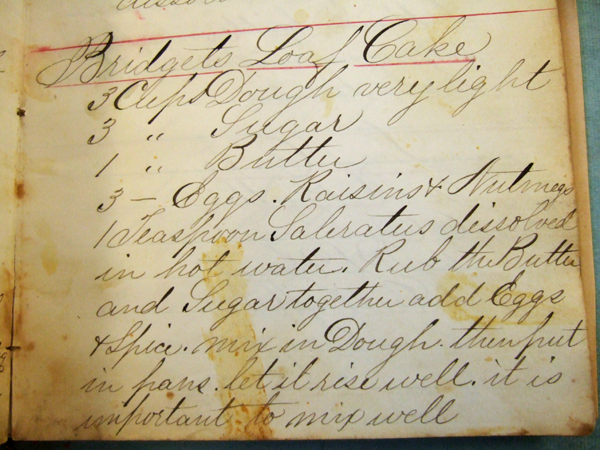

The recipe I found the most interesting is this one, for “Bridget’s Loaf Cake”:

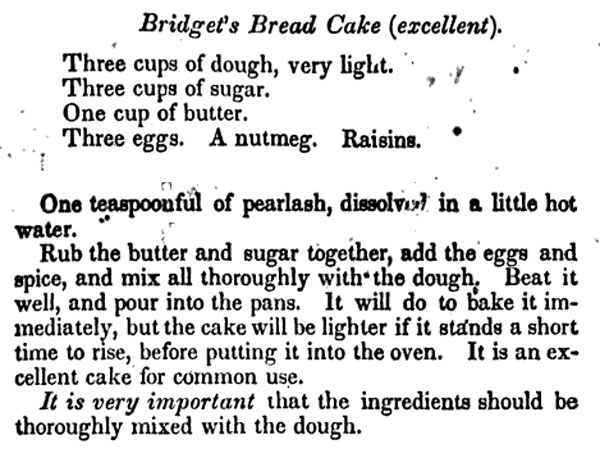

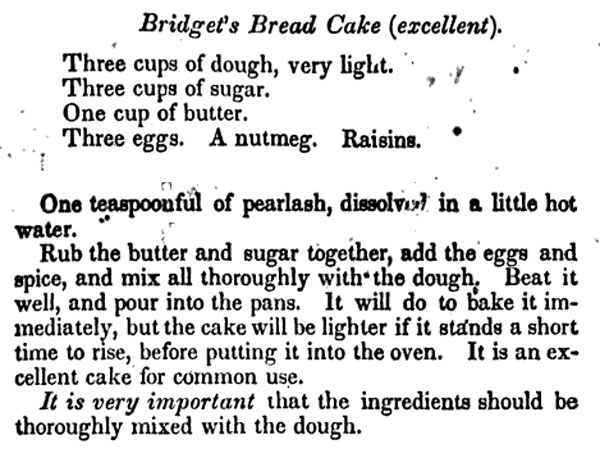

I recognized this recipe as the one that Mark Zanger, the author of The American History Cookbook, identifies as the firsts explicity Irish recipe to appear in print in an American book. He cites it as coming from Mrs. Beecher’s domestic Receipt Book (1848), and sure enough, it is the same recipe as in Mrs. Lintz’s manuscript:

The 1840s were a decade of dramatic increase in immigration to America, due in part to the famine that hit Ireland, decimating the primary food source of potatoes. The political situation was far more complicated than just that, but the results was the emigration of about 2 million Irish to points around the globe; 1.5 million landed in American; and by the 1860s, one in every four New Yorkers was born in Ireland.

Many single Irish women immigrated here to take positions in domestic service, as there was an incredible demand for servant labor in American household. As a result, “Bridget” became the generic, ethnically-charged term for a servant. Bridget learned American cooking from her Misses; and in turn, influenced the American kitchen with cuisine brought from home.

Mrs. Lintz’s Loaf Cake recipe isn’t just important because of the cultural trend it reflects; but because she took the time to copy it from Mrs. Beecher’s Receipt book, it illustrates that this recipe was actually popular and it was being made in family kitchens.

***

Bridget’s Bread Cake

From Mrs. Beecher’s Domestic Receipt Book, by Catherine Beecher, 1848.

Bake time and temperature from The American History Cookbook by Mark Zanger

For the bread dough:

3 cups flour

1 tbsp oil

1 tsp salt

1 tsp yeast (or one packet)

1 cup warm water

This is a basic bread recipe I received from a great breadmaking class at the Brooklyn Brainery. Frozen bread dough can also be subsituted.

Place water in a clean, glass bowl; sprinkle yeast over surface. Whisk gently with a fork. Set aside.

Combine dry ingredients and oil, mixing with a fork. Add yeast water, stirring to combine.

As the dough comes together, form into a ball and place on a clean surface. Knead for 3 minutes, adding more flour or water as necessary. A wet dough works well for this recipe.

Place in a bowl and cover with a clean towel. Allow to rise for one hour.

For the Bread Cake:

3 cups sugar (you can use 1/2 cup brown and 1 cup white)

1 cup (2 sticks) butter, at room temperature

1 nutmeg, grated (approximately 2-3 teaspoons ground)

1 tsp baking powder

3 medium eggs (or 2 large)

1/2 cup raisins

Using a fork, cream together butter and sugar. Add nutmeg and baking powder, then eggs. Mix until thoroughly combined. Stir in raisins.

Add ball of bread dough to sugar mixture. Combine thoroughly using your hands: first fold the dough into itself, incorporated the sugar mixture; then squeeze and mash the dough with you fingers until you have a dense, sticky batter.

Set aside and allow to raise for 20-30 minutes. Butter two small loaf pans and preheat your oven to 425 degrees.

Bake for 15 minutes, then reduce heat to 350 degrees and bake 15 minutes more. Remove from oven and cool, in pan, on a wire rack. Remove from pan and allow to cool completely on the wire rack, or serve immediately.

**

At these proportions, the Bread Cake came out super ooey gooey buttery sugary, to the point where it formed caramel on the bottom of the pan, like an upsidedown cake. Overall, the texture was something like bread pudding. I don’t think that was the intended result of this recipe, but I don’t think I care. The texture is amazing and delicious. Sadly, the caramel bottom stuck to the bottom of the pan, but I bet it would be even more awesome with it.

I wasn’t so fond of the flavor, though: heavy doses of nutmeg in my baked goods just make me think of the 19th century, but doesn’t hold any appeal to my modern taste buds. If I were to make this again, I would use apples and cinnamon instead of nutmeg and raisins I would line the loaf pan with parchment, so I could lift the whole thing out without losing the caramel, and I would serve it hot from the oven. In fact, I think I might do just that. I’ll let you know how it goes.

Bridget’s Bread Cake – not particularly photogenic.