This guy:

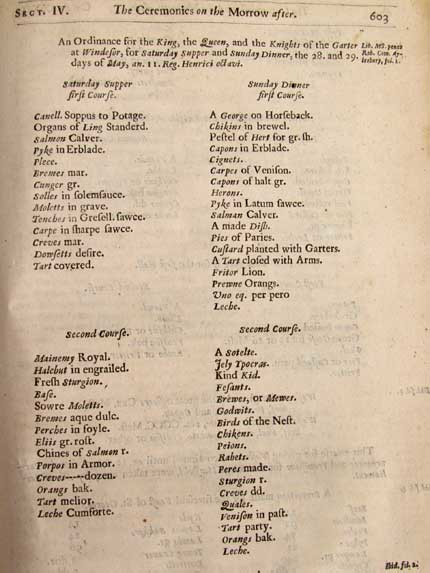

Ate this in 1520:

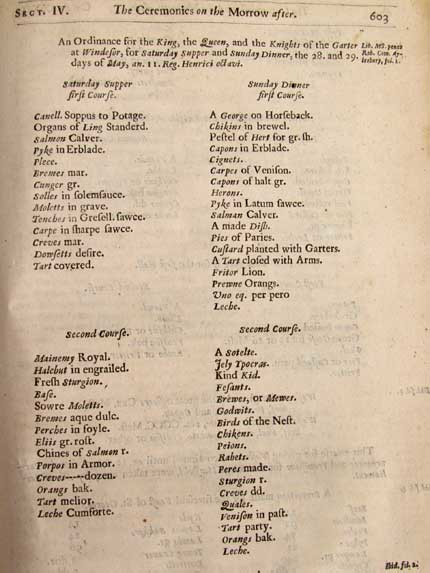

And this in 1526:

More details on these menus can be found here, on Ivan Day’s phenomenal blog.

This guy:

Ate this in 1520:

And this in 1526:

More details on these menus can be found here, on Ivan Day’s phenomenal blog.

This menu comes from Fifteen Cent Dinners for Families of Six, a pamphlet released during one of the nation’s worst depressions, the Panic of 1873. The author, Juliet Corson, strives to lay out decent meals for families on a restricted budget (I once spent a week eating her suggested diet, read about it here). She allows for a bit of holiday joy with this Christmas dinner for a dollar, which is the almost the exact same Christmas dinner the Cratchits ate in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.

Notice the special attention paid to the price of ingredients, which she says are based on the prices at Washington Market; the 5-lb turkey, and the last line: “After you have eaten it, think if I have kept my promise to tell you how to get comfortable meals at low prices.”

One of the most emblematic cookbooks in American history is Fannie Farmer’s Boston Cooking-School Cookbook. Called “The Mother of Level Measurements,” Farmer is both credited with bringing standardization to American recipes but, as a result, destroying the soul of American cuisine.

Her cookbooks were promoted as practical and economical: a kitchen guidebook for the everyday women. But it also included simplified recipes for high-end dishes that allowed any housewife to produce them in her own kitchen.

Interestingly, in the back of the book, she includes a menu for a “Full Course Dinner”: twelve courses designed for the most upscale dinner party. This menu is republished below. It would be a hellavu party.

First Course

Little Neck Clams or Bluepoints with brown bread sandwiches. Sometimes canapes are used in place of either. For a gentleman’s dinner, canape’s accompanied with Sherry wine are frequently served before guests enter the dining room.

Second Course

Clear soup with bread sticks, small rolls or crisp crackers. Where two soups are served, one may be a cream soup. Cream soups are served with croutons. Radishes, celery or olives are passed after the soup. Salted almonds may be passed between any of the courses.

Third Course

Bouchees or rissoles. The filling to be of light meat.

Fourth Course

Fish baked, boiled or fried. Cole slaw dressed cucumbers or tomatoes accompany this course; with fried fish potatoes are often served.

Fifth Course

Roast saddle of venison or mutton, spring lamb, or fillet of beef potatoes and one other vegetable.

Sixth Course

Entree made of light meat or fish.

Seventh Course

A vegetable. Mushrooms, cauliflower, asparagus or artichokes are served.

Eighth Course

Punch or cheese course. Punch when served always precedes the game course.

Ninth Course

Game with vegetable salad, usually lettuce or celery; or cheese sticks may be served with the salad and game omitted.

Tenth Course

Dessert, usually cold.

Eleventh Course

Frozen dessert and fancy cakes. Bonbons are passed after this course.

Twelfth Course

Cracker, cheese and cafe noir. Cafe noir is frequently served in the drawing and smoking rooms after the dinner. After serving cafe noir in drawing room, pass pony of brandy for men, sweet liquenr (Chartrense, Benedictine ,or Parfait d Amour) for women, then Creme de Menthe for all.

The following menu was served at the first elementary or uncooked banquet ever spread in this country, given by the authors, June 18, 1903… The object was more to show the numerous and attractive dishes that could be prepared from uncooked foods, than to observe or follow any particular dietetic rule or law.

—Uncooked Foods and How to Use Them, by Eugene and Molly Griswold Christian.

Here’s my menu for tonight’s lecture, Reducing Recipes: Historic Remedies for Your Expanding Waistline. If you’re in the NYC area, you can get tickets here to taste all these good things. And I have to say, everything turned out delicous–not just delicious “for diet food!”

Click the links to learn more about each course.

Dr. Kellogg’s Protose Meatless Balls

–Fletcherizing Demo-

J.W. Wiggelsworth’s “Concentrated Nutrition”

Richard Simmons’ Farewell to Fat Raspberry Brownie Points

The holidays have come and gone, but file this away for next year: a Christmas dinner based off of Dickens’s classic, a Christmas Carol. The following menu has been pulled from the description of Bob Crachit’s feast on Christmas Eve — not a sad, meager meal, as it is often portrayed in film interpretations of the story. But rather a proud day, when the family pooled their modest resources to create a filling feast and a happy occasion. Read the excerpt from the original story here.

The menu items are linked to the historic or contemporary recipes.

Roast Goose with Sage and Onions

Gravy

Mashed Potatoes

Apple Sauce

Christmas Plum Pudding in Blazing Brandy

Cock-tail; Gin Sling; Hot Spiced Rum; Charles Dickens Punch

This was the first time I had ever roasted a goose and I was a little disappointed. Water birds have immense chest cavities, so what appears to be a large bird actually does not has a lot of meat. A ten pound goose produced a tiny pile of meat; although what few bites I had tasted good. Knowing that, it’s not a surprise that Scrooge buys the family a big, meaty turkey at the end of the book.

I wasn’t sure how the plum pudding was going to light on fire, but after some discussion, we doused the hot dessert in warm brandy and held a lighter to it, and it was soon engulfed in flame. It was a very impressive end to the meal.

We also played a rousing game of Snapdragon, which involves plucking raisins out of a pan of burning brandy. It’s a lot less dangerous that it sounds.

Left: What a centerpiece! From Betty Crocker’s Party Book, 1960.

Left: What a centerpiece! From Betty Crocker’s Party Book, 1960.Turkey has been and always will be the star of a traditional Thanksgiving menu, but 18th and early 19th century menus commonly featured multiple meats. Local game, like venison, often made an appearance. Recipes for mince meat pie and “Thanksgiving Chicken Pie” abound in historic text. And Sarah Josepha Hale, the Anna Wintour of the 19th century, insisted that turkey be served along side ham or tongue.

This menu, from Buckeye Cookery (1877) shows the true bounty and diversity of what could grace your Thanksgiving table in the 19th century:

But some believed turkey shouldn’t make an appearance on the Thanksgiving table at all. John Harvey Kellogg, of cornflakes fame, was an ardent vegetarian. He, like many early veggies, believed that animal flesh could make a man violent and destroy digestion. Below, two flesh-free menus from his kitchens:

It’s likely he may have also suggested a main course of Roast Protose with Dressing. Protose, a mysterious, early faux meat, was produced commercially up until the last decade. It was made from (possibly) some combination of peanut butter and wheat gluten.

And lastly, let’s kitsch it up a bit with a menu from Betty Crocker’s Party Book, published 1960. Please note the lemon jell-o and horseradish salad.

For historic Thanksgiving recipes interpreted for the modern kitchen, including pumpkin pie, squash, and stuffing, go here!

Eaten on this day in 1851 at Niblo’s Saloon. I think my favorite dishes are the Chicken Sallad and the Beef Tongues, both served in “gelee”; the Pigeons and the Widgeons; and (no party is a party without) Charlotte Russe. I don’t know which would have been my favorite ornamental piece; probably the Fruits of Industry.

The St. Nicholas Society of New York was founded by a man named John Pintard. Pintard was largely responsible for the invention of our modern Christmas traditions, along with society members Washington Irving and Clement Clark Moore. These men were obsessed with the Dutch history of New York, and they appropriated St. Nick as New York City’s patron saint.

I’m reading a fascinating book on Christmas traditions, The Battle for Christmas by Stephen Nissenbaum. It was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, and is a wonderful read this time of year. Nissembaum outlines the transition of the Christmas holidays from a time of gluttony and drunkenness to a celebration of domesticity. On the St. Nicholas Society and its members, Nissenbaum has this to say:

…It was John Pintard who brought St. Nicholas to America, in an effort to make that figure both the icon of the New York Historical Society and the patron saint of New York City….In the 1810s, Pintard organized and led elaborate St. Nicholas’ Day banquets for his fellow members of the New York Historical Society…

…Nobody has ever found contemporaneous evidence of such a St. Nicholas cult in New York during the colonial period. Instead, the familiar Santa Claus story appears to have been devised in the early nineteenth century…It was the work of a small group of antiquarian minded New York gentlemen–men who knew one another as members of a distinct social set. Collectively, those men became known as the Knickerbockers…

In short, the Knickerbockers felt that they belonged to a patrician class whose authority was under siege. From that angle, their invention of Santa Claus was part of what we can now see as a larger, ultimately quite serious cultural enterprise: forging a pseudo-Dutch identity for New York, a placid “folk” identity that could provide a cultural counterweight to the commercial bustle and democratic ‘misrule’ of early 19th century New York.