A cheesecake recipe for a 19th century Photographer.

A cheesecake recipe for a 19th century Photographer.

The History

College was one of the most difficult and demanding times of my life. I looked for small ways to escape the pressure, like ducking into Attenson’s Antiques on Coventry, a maze of rooms stuffed with treasures. In the back corner was a bookshelf used as a dumping ground for an ever-growing collection of photographs. Box after box, picked up at estate sales, ended up in this nook. If the day was quiet enough, the shop owners would let me spread out on the floor to go through the black and white lives of people long dead. After an hour or two, I’d have a pile of images set aside. I’d pay ten or twenty dollars, and take my new friends home.

An albumen print of General Tom Thumb and his wife, Lavinia.

If you’ve ever spent time sorting through thrift store images, you’ve certainly come across a type of photography known as albumen printing. Albumen photographs are characterized by their sepia tone, glossy sheen, and sometimes a metallic shine in the dark parts of the image. They’re also printed on a thin piece of paper glued to a thicker cardboard stock.

Albumen is made of egg whites. This sticky substance allowed photographer to adhere photo chemicals to glass plates, allowing for the first commercially viable form of reproducible photography. Additionally, when painted on paper, albumen created an ultra smooth surface on which to float photosensitive chemicals; the result was a highly detailed image when the photo was printed.

The process was revolutionary and used for much of the second half of the 19th century, and even into the 20th. However, producing albumen paper used a lot of eggs whites and left a byproduct of a ton of egg yolks. Some of those yolks could have been used in this recipe for “Photographer’s Cheesecake” published in The Wilder Shores of Gastronomy: Twenty Years of Food Writing.

.

The Recipe

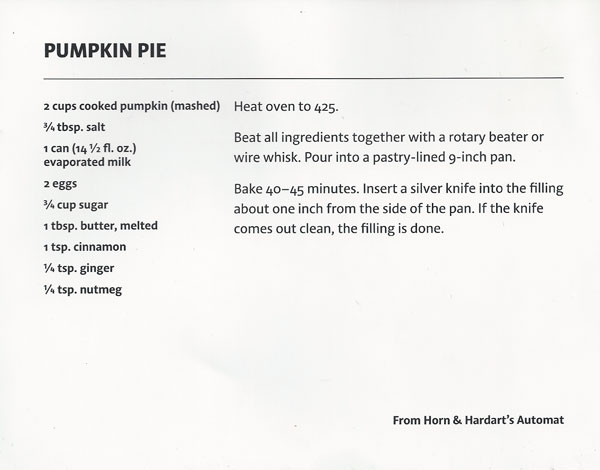

In 1861, The British Journal of Photography suggested, to the amateur photographer, that he could use his excess egg yolks to make a cheese cake. One day, after making a meringue, I had a lot of yolks on my hands and decided to give it a try. It required very few ingredients and took less than ten minutes to assemble. Problems started to arise when I baked it: the filling was still liquid although I had baked it longer than the recipe suggested. When I put it in the fridge overnight, it was solid, but liquefied at room temperature. I still ate it, though.

The Photographer’s Cheesecake

Originally printed in The British Journal of Photography, 1861

Reprinted in The Wilder Shores of Gastronomy

To convert the yolks of eggs used for albumenizing to useful purposes: Dissolve a quarter of a pound of butter in a basin placed on the hob, stir in a quarter of a pound of pounded sugar, and beat well together; then add the yolks of three eggs that have been previously well-beaten; beat up altogether thoroughly; throw in half a grated nutmeg and a pinch of salt; stir, and lastly add the juice of two fine-flavoured lemons, and the rind of one lemon that has been peeled very thin; beat all up together thoroughly and pour into a dish lined with puff-paste, and bake for about twenty minutes. This is a most delicious dish.

1 stick butter, softened

1/2 cup sugar

3 egg yolks, beaten

1/2 of a freshly grated nutmeg

Pinch of Salt

Juice of two small lemons

Zest of one lemon

Puff Paste (store bought is ok!)

Beat (using an electric mixer, if you like) butter and sugar until light and fluffy. Add egg yolks, one at a time, mixing after each addition. Add nutmeg and salt; mix. Add lemon juice and zest; mix. Pour into a baking dish lined with puff paste, bake at 350 degrees for 35 minutes.

The Results

Out of the oven.

Out of the oven.

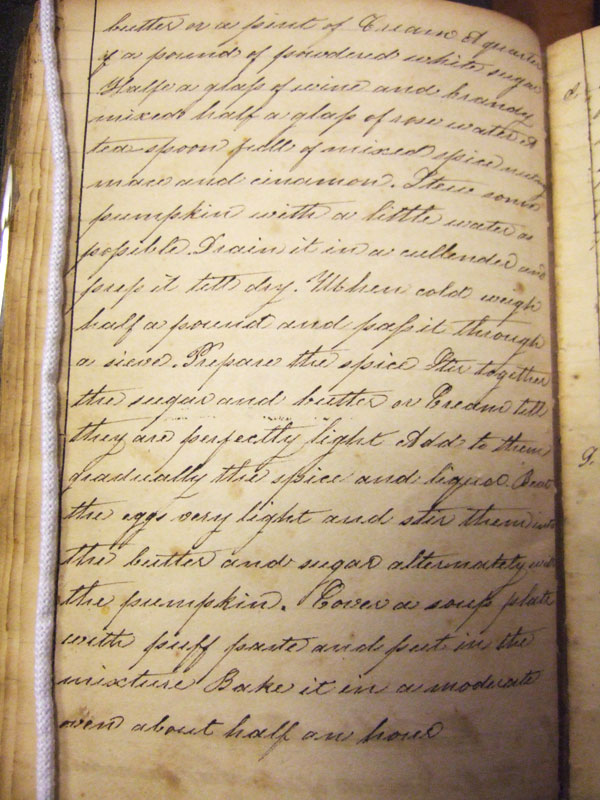

Honestly, it tasted great! I loved the citrus, which complemented the nutmeg well. At the same time, the technical aspects of the recipe didn’t work. It was goopy and runny and not at all right–and I don’t think it was my mistake. perhaps this recipe was originally published as a joke, not as a real recipe? Which seems silly, because what on earth did those photographers do with all those egg yolks anyway?

A mediocre Galette des Rois.

A mediocre Galette des Rois.

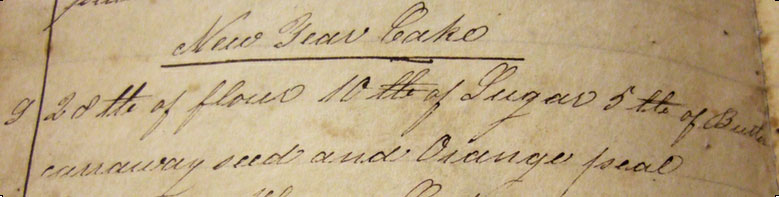

Horn and Hardart’s automat, from

Horn and Hardart’s automat, from