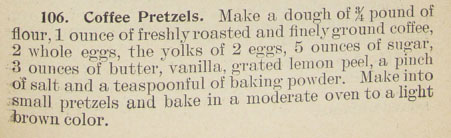

A coffee-cookie-pretzel.

A coffee-cookie-pretzel.

The History

This is the last recipe I’ll be featuring from The Practical Cookbook; it’s a for a German staple with a “twist”: coffee pretzels.

The origin of pretzels are shrouded in myth. Scholars believe that they were first baked around 610 AD in a monastery in Northern Italy or Southern France. Their creation may have been associated with Lent; at the very least, there has long been a Christian association with them. The classic pretzel shape has been said to represent arms crossed in prayer and the Holy Trinity.

Pretzels have long been considered an inseparable companion to beer in German tradition. Pretzel making in Germany was, historically, very regional, featuring a variety of flavors, textures, and shapes. In Bavaria, starting in the mid-19th century, pretzels were dipped in a lye and water bath before baking, which gave them a deep brown color and distinctive taste. These Bavarian-style pretzels are the ones we’re most familair with in the United States, known simply as “soft pretzels.” Swabian pretzels have thin arms and a fat belly; pretzels from Fanconia could be flavored with anise; while pretzels from other areas could be sprinkled with caraway, sesame, or poppy seeds

I decided to try this particular pretzel recipe because, honestly, I’ve never seen anything like it before.

The Recipe

Coffee Pretzels

adapted from From The Practical Cook Book by Henriette Davidis, 1897 (English Version)

I busted out my kitchen scale for this one.

8 ounces flour

1 ounce finely ground coffee

Pinch salt

1 teaspoon baking powder

3 ounces unsalted butter, room temperature

5 ounces white sugar

Zest of one lemon

2 eggs

2 egg yolks and 2 egg whites, separated

In a medium bowl, whisk together flour, coffee, salt, and baking powder. In the bowl of an electric mixer, beat together sugar, lemon zest, and butter until light and fluffy. Add eggs and egg yolks, one at a time, mixing after each addition. With mixer on low, slowly add dry ingredients. Scrape bowl and mix until evenly combined.

Flour a work surface (parchment, cutting board, non-stick mat). Take dough about 1/2 cupful at a time, rolling it first in the flour, then gently rolling dough into long “snakes.” Using fingers to apply pressure to dough, roll back and forth, and gently stretching it side to side. When dough is about 1/2 in thick, cut into 4-5 inch length and fold into a traditional pretzel shape. Place on a cookie sheet.

Wash pretzels with egg whites and sprinkle with sugar. Bake at 375 degrees for 10 minutes. Remove from cookie sheet and cool on a wire rack.

The Results

These turned out more like a coffee shortbread than a pretzel. However, I am a poor judge of their flavor, because I hate coffee. Tomorrow, I’ll distribute to my coworkers, and we’ll see what the verdict is.

Update (1/29): The results are in! The texture of these little cookies was generally praised, as was the sprinkled-sugar topping. But opinions on the flavors were extremely divided: either tasters loved the strong coffee flavor, especially for dipping IN their morning coffees; other thought it was the most terrible taste they’d ever had, like chewing on coffee grounds.

A Silesian Cheese Cake!

A Silesian Cheese Cake!

Moxy helps the dough rise.

Moxy helps the dough rise. What is this? I don’t know.

What is this? I don’t know. Mixing the Topping.

Mixing the Topping. Gummy, but decent.

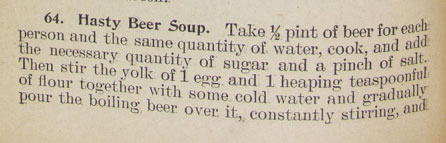

Gummy, but decent. Hot German beer soup.

Hot German beer soup.

Beer, measured for soup.

Beer, measured for soup.