I haven't decided if this image is racist or super racist.

“It would be well perhaps if we first altered some of our preconceived notions regarding the Chinese diet. Many people think that the Chinese live entirely on rice; some believe that rats also occupy and important place on the daily menu. Both ideas are mistaken and should be discarded.” – Corinne Lamb

In our ongoing look at the culinary holdings at the New York Historical Society, today we explore the The Chinese Festive Board published in 1935 by author Corinne Lamb.

Written by a woman who seems to have lived in China for a number of years, it’s one of the earliest books I’ve seen on Chinese cooking in China (as opposed to Chinese-American cuisine). The first half is all about Chinese dinner customs and the second half is an extensive recipe book. Lamb also includes helpful vocabulary for ordering in Chinese restaurants.

The tone of the book’s writing is bizarre: it simultaneously condescends to Chinese culture, while praising the deliciousness of its food. The author straight-up uses ethnic slurs throughout the book. Keep in mind, this is a time in our nation’s history when immigration was banned from China.

The book is a window into another era and we are definitely looking through the lens of an American perspective on Chinese life. The recipes are interpreted to use ingredients readily available to an American housewife. I decided to throw a 1930’s Chinese dinner party, following a sample menu from the book, as well as her description of a formal Chinese dinner party.

Below, a menu Lamb describes as a typical dinner in the home of a middle-class Chinese family:

Dinner parties, the author points out, were nearly always given in restaurants, and were nearly always for men alone; but since I wanted to cook and eat the recipes myself, I decided to bend the rules a little bit and have the party in my own home. First, an invitation was necessary. Lamb provide an example of one in her book, printed on an elegant piece of rice paper that had been gently pasted into one of the pages (see left). Translated, it says: “The fifth month, the twenty-third day, one o’clock in the afternoon ‘the cups will be cleaned and your presence will be awaited’. Mr. Ma Lien-liang respectfully writes: ‘The feast is arranged’ outside of Hataman Gate, Bean Curd Lane, No. 7.”

I should have mailed a beautiful rice paper square to my guests, but instead I just texted them. They accepted: two friends from Brooklyn, Brandon and Madeline, the latter of whom spent a year living in China for work.

They came over on Friday evening, and while I finished prepping the food, I fed them peanuts and cups of green tea, which Lamb describes as the proper way to begin a feast. Then, just before I began cooking the food, we sat down for a round of drinking games.

Lamb says drinking takes up only the earlier courses of the meal and is set aside once substantial foods come out. The drink of choice is Chinese rice wine, which Lamb describes as being close to sherry, and Madeline describes as “gross.” The liquor store didn’t have it, so I selected a nice bottle of sake, that I poured out in handsome shot-glasses, for lack of the appropriate vessels.

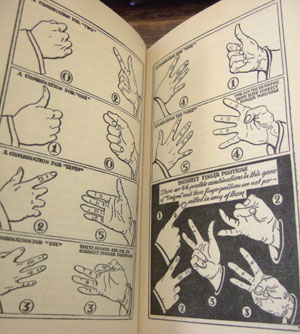

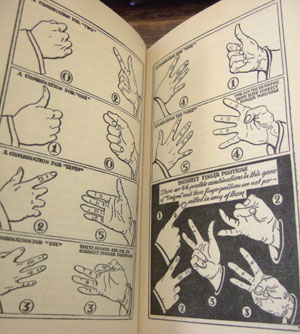

The game of choice in China is hua ch’uan, or “matching fingers”, a drinking game still played to this day. It involves two people throwing fingers, similar to rock-paper-scissors, and each player “loudly shouts his estimate of the total number of fingers shown on both hands.” If one player guess correctly, the other has to drain his glass. Examples of hand positions are below:

It’s harder than it seems.

Madeline also mentioned that beer was now an equally acceptable drink in China, which Lamb mentions was gaining popularity in her time. Madeline also said that drinking now seems to last through the entirety of the meal, accompanied by a tradition of toasting: Madeline toasted me for having them over, and we both drank. Madeline toasted Boyfriend Brian as well, and they both drank. I toasted Madeline to thank her, and we both drank… and so on. After we ran out of sake, and turned to beer, it begun to feel a little bit like a power hour.

Then, thankfully, it was time to eat. Lamb describes her recipes as coming “…Mostly from well known restaurants in Peiping…” known today as Beijing, in the north-east of China. I got four pans going on my stove top, three melting lard, one with olive oil, and continued to play the drinking games while I cooked. The recipes seemed so simple that they couldn’t possibly be delicious, let alone authentic. But I was ready to find out.

Homestyle Chinese spread.

My menu was as follows, based on the recipes Lamb provided in her book.

***

Rice

I was nervous about this recipe, it being vastly different than the “one cup of rice to one and a half cups water” formula that I know of. But I tried it, using my big Calphalan pot with the inset strainer. And the rice turned out just as promised: not too wet or gooey, not too dry either. Just perfect, with every grain an individual. I was amazed.

***

Fried Pork Balls

I made these slightly differently, after looking at another of Lamb’s recipe for Pork Meat Balls. I rolled them and then squashed them flat, which let me use less lard to cook them and allowed a greater surface area to get crispy. These were hands-down my favorite. Crispy on the outside, soft and tender in the middle; so savory with an appealing texture. I ate the leftovers for the next two days and I would absolutely make them again.

***

Sauteed Leeks and Pork

***

String-Beans and Pork

The sauteed pork dishes were the favorites of my guests, who loved to combine them both in one bowl of rice. The soy and ginger made a lovely sauce, and the string beans were cooked to perfection.

***

Eggs and Mushrooms

There wasn’t a recipe for this dish in Lamb’s book, so I created one based on the recipe she gives for “Scrambled Eggs with Shrimps.”

6 eggs

1 cup mushrooms, sliced

3 tsp Chinese Wine

2 tsp lard

1 pinch salt

1 pinch black pepper

With a pair of chopsticks, beat eggs thoroughly. Add salt, pepper and wine and beat again. Heat the lard in a frying pan and sautee the mushrooms until tender, then add the egg mixture, and cook as you would scrambled eggs.

***

On Chinese wine, Lamb says “It will be noted that many of these recipes call for Huang Chiu. or Chinese wine. Sherry is recommended as a substitute. With the repeal of the 18th amendment it should not be long before Chinese wine will be available in every American city, and when that is so its use in in preparing Chinese food will be found preferable.” It wasnt’ available at my local liquor store, so I used a Japanese plum wine that taste very much like sherry. This, mixed with the eggs, was AWESOME. I don’t even like eggs, and I hate mushrooms, but this dish was just as good as everything else on the table. The wine was really a star when mixed with the eggs. It was a surprise.

We ate in the way lamb suggests, Family-style, using only bowls and a pair of k’uia tzu, or “quick little boys,” or better known here as “chop sticks.” We topped big piles of rice with the sauteed dishes, sometime two or more at once. We ended in a very Chinese-American way with more tea and a few baked sweets: sugar cookies, lotus seed cakes, and “R-rated” fortune cookies; all of which were from Chinatown in Manhattan.

Madeline somehow found "R-rated" fortune cookies.

The food was delicious–really delicious. But was it authentic? I have no clue– but I’m looking in to it.

What do you think?

image courtesy Bunches and Bits {Karina}

image courtesy Bunches and Bits {Karina}