Brandon brought me this great article: an explanation for the word “Brunch,” from Punch, or The London Charivari, August 1, 1898.

Will I see you later for suckfast? Or do you want to get together tomorrow for brupper?

Brandon brought me this great article: an explanation for the word “Brunch,” from Punch, or The London Charivari, August 1, 1898.

Will I see you later for suckfast? Or do you want to get together tomorrow for brupper?

Pumpkin Pudding

Half a pound of stewed pumpkin Three Eggs A quarter of a pound of fresh butter or a pint of Cream A quarter of a pound of powdered white sugar Half a glass of wine and brandy mixed Half a glass of rosewater teaspoon full of mixed mixed spice nutmeg, mace, cinnamon. Stew some pumpkin with as little water as possible. Drain it in a cullender and prep it till dry. When cold, weigh half a pound and pass it through a sieve. Prepare the spice. Stir together the sugar and butter or Cream till they are perfectly light. Add to them gradually the spice and liquid. Beat the eggs very light and stir them into the butter and sugar alternately with the pumpkin. Cover a soup plate with puff paste and put in the mixture. Bake it in a moderate oven about half an hour.

This recipe was written well over a hundred years ago, by a Maria Lefferts. The Lefferts, one of the first families of Brooklyn, lived in the area that is now known as Prospect Park; one of their homes still remains as a historic site. Their papers reside in the collections of the Brooklyn Historical Society, which is where I came across this handwritten cookbook, and this recipe for Pumpkin Pudding.

Pumpkin Pudding is better known today as Pumpkin Pie. I love cooking an American standard from a historic recipe because it often gives me a new perspective. After looking at recipes from the late 18th century, I retronovated my yearly pumpkin pie recipe with a 1/4 cup of brandy and 1/3 cup of pure maple syrup. And I seldom make an apple pie without a dash of rosewater and some white wine.

Mrs. Leffert’s recipe dates to about 1820; her instructions are refreshingly precise, almost modern. In most cookbooks from that time, let alone handwritten cookbooks, recipes can be as verbose as a list of ingredients.

***

Pumpkin Pudding

From the handwritten cookbook of Maria Lefferts, c. 1820.

1/4 lb (1 stick) butter or 1 pint cream

1/4 lb (1/2 cup) super fine sugar

1/4 cup a glass of wine and brandy (I used brandy only)

1/4 cup a glass rose water

1 tsp mixed nutmeg, mace and cinnamon (I used 1/4 tsp each nutmeg and mace, and 1/2 tsp cinnamon)

1/2 lb (1 cup) stewed pumpkin

2 large eggs

Preheat oven to 325 degrees. In an electric mixer, cream butter and sugar until light and fluffy. With the mixer on low, add spices and then brandy and rosewater. Beat eggs with a fork until light, then add them to the butter mixture, alternating with the pumpkin.

Press a puff paste into a pie pan, and fill with pumpkin mixture. Bake for one hour. Allow to cool completely before serving. Custard pies are always better the next day.

For the crust, I used a basic puff paste recipe from the book Puff.

***

I chose to use butter, instead of cream, because it is Leffert’s first suggestion, and it’s not an ingredient normally used in pumpkin pie. I was curious how it would change the texture. However, by the time the pie was mixed and ready for the oven, the butter had made it a lumpy mess.

Lumpity.

Lumpity.I was also extremely apprehensive about how much rosewater was going into this pie. “1/2 a glass,” based on the proportion of the brandy I was adding, I estimated at being a 1/4 of a cup. As I measured the odorous liquid, I wondered if I shouldn’t cut it down to two tablespoons. I looked at Roommate Jeff, who had creeped into the kitchen. “Should I put less rosewater in or should I just stop being a pussy and follow the recipe?”

“Stop being a pussy.”

And in went the rosewater. While I was making the pie, the entire kitchen stunk of rosewater. While the pie was baking, a sickening-sweet rosewater smell drifted from the oven. When it was finally time to cut the pie and try a taste, the only flavor that my taste buds could understand was rosewater.

Blech. While I don’t mind rosewater in appropriate quantities, that’s all I could taste in the recipe: the sweet, floral, citrus notes of distilled rose petals, in nauseating quantities. Even if I reduced the quantity of rosewater, I’m not sure how I would feel about it paired with pumpkin. I tend to enjoy it more is dishes that are slightly acidic, like apple pie.

More than that, the texture was very unappealing. Oddly, it had a gritty mouth-feel.

At any rate, the 190-year-old Pumpkin Pudding is coming into work with me today, so we’ll see what the verdict is from my coworkers. They’re nerds, so they’ll at least appreciate the history. Happy Thanksgiving!

This post is the first in a series of three celebrating the re-opening of the New York Historical Society. We’re going to focus on examples from the NYHS’s culinary holdings.

Today, we’re looking at a beautiful manuscript from 19th century New York; beautiful both for its physical appearance, and for the important information it gives us about daily life in the city 100 years ago.

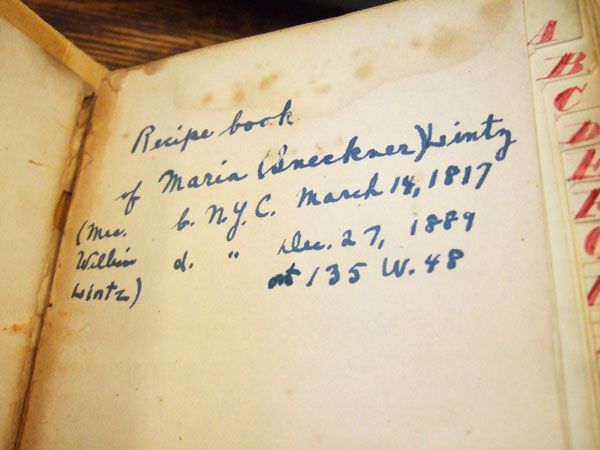

The book is written by Mrs. Wilbur Lintz (nee Maria Sneckner), who was born in 1817 and passed in 1889. During her life, she decided to record her favorite recipes and culinary knowledge. Overall, this book gives us a peek into what was being cooked in a middle-class, New York kitchen.

“Recipe book of Maria (Sneckner) Lintz (Mrs. Wilbur Lintz) b. N.Y.C. March 14, 1817 d. ” Dec 27, 1889 at 135 w. 48″

Mrs. Lintz was a very organized woman; her cookbook is alphabetically indexed in a way that allowed her to add to her recipes over time.

Sneckner is an old Dutch name, and in that line, the manuscript features several traditional New Amsterdam-style recipes. The recipe book includes three different recipes for New York Cakes, a cookie flavored with caraway. In the Dutch tradition, these cakes were passed out to visitors on New Year’s Day; the practice of visiting on New Year’s was revived by the upper and middle classes of New York in the middle of the 19th century.

Additionally, this manuscript features recipes at the height of their fashion and modernity, like this one, at left, for Parker House Rolls.

These rolls were invented in the Parker House Hotel of Boston in the 1870s and quickly became very fashionable. “They are made by folding a butter-brushed round of dough in half; when baked, the roll has a pleasing abundance of crusty surface. Recipes for Parker House rolls first appeared in cookbooks during the 1880s.” (Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America, 2004)

Parker House Rolls.–One quart of cold boiled milk, two quarts of flour. Make a hole in the middle of the flour, take one half cup of yeast, one half cup of sugar, add the milk, and pour into the flour, with a little salt; let it stand as it is until morning, then knead hard, and let it rise. Knead again at four o’clock in the afternoon, cut out ready to bake, and let them rise again. Bake twenty minutes.–Mass. Ploughman.

—“Parker House Rolls,” New Hampshire Sentinel, April 9, 1874 (p. 1) (sourced from The Food Timeline)

The Parker House still exists, and still serves its famous rolls, as well as its other great creation, The Boston Cream Pie.

The recipe I found the most interesting is this one, for “Bridget’s Loaf Cake”:

I recognized this recipe as the one that Mark Zanger, the author of The American History Cookbook, identifies as the firsts explicity Irish recipe to appear in print in an American book. He cites it as coming from Mrs. Beecher’s domestic Receipt Book (1848), and sure enough, it is the same recipe as in Mrs. Lintz’s manuscript:

The 1840s were a decade of dramatic increase in immigration to America, due in part to the famine that hit Ireland, decimating the primary food source of potatoes. The political situation was far more complicated than just that, but the results was the emigration of about 2 million Irish to points around the globe; 1.5 million landed in American; and by the 1860s, one in every four New Yorkers was born in Ireland.

Many single Irish women immigrated here to take positions in domestic service, as there was an incredible demand for servant labor in American household. As a result, “Bridget” became the generic, ethnically-charged term for a servant. Bridget learned American cooking from her Misses; and in turn, influenced the American kitchen with cuisine brought from home.

Mrs. Lintz’s Loaf Cake recipe isn’t just important because of the cultural trend it reflects; but because she took the time to copy it from Mrs. Beecher’s Receipt book, it illustrates that this recipe was actually popular and it was being made in family kitchens.

***

Bridget’s Bread Cake

From Mrs. Beecher’s Domestic Receipt Book, by Catherine Beecher, 1848.

Bake time and temperature from The American History Cookbook by Mark Zanger

For the bread dough:

3 cups flour

1 tbsp oil

1 tsp salt

1 tsp yeast (or one packet)

1 cup warm water

This is a basic bread recipe I received from a great breadmaking class at the Brooklyn Brainery. Frozen bread dough can also be subsituted.

Place water in a clean, glass bowl; sprinkle yeast over surface. Whisk gently with a fork. Set aside.

Combine dry ingredients and oil, mixing with a fork. Add yeast water, stirring to combine.

As the dough comes together, form into a ball and place on a clean surface. Knead for 3 minutes, adding more flour or water as necessary. A wet dough works well for this recipe.

Place in a bowl and cover with a clean towel. Allow to rise for one hour.

For the Bread Cake:

3 cups sugar (you can use 1/2 cup brown and 1 cup white)

1 cup (2 sticks) butter, at room temperature

1 nutmeg, grated (approximately 2-3 teaspoons ground)

1 tsp baking powder

3 medium eggs (or 2 large)

1/2 cup raisins

Using a fork, cream together butter and sugar. Add nutmeg and baking powder, then eggs. Mix until thoroughly combined. Stir in raisins.

Add ball of bread dough to sugar mixture. Combine thoroughly using your hands: first fold the dough into itself, incorporated the sugar mixture; then squeeze and mash the dough with you fingers until you have a dense, sticky batter.

Set aside and allow to raise for 20-30 minutes. Butter two small loaf pans and preheat your oven to 425 degrees.

Bake for 15 minutes, then reduce heat to 350 degrees and bake 15 minutes more. Remove from oven and cool, in pan, on a wire rack. Remove from pan and allow to cool completely on the wire rack, or serve immediately.

**

At these proportions, the Bread Cake came out super ooey gooey buttery sugary, to the point where it formed caramel on the bottom of the pan, like an upsidedown cake. Overall, the texture was something like bread pudding. I don’t think that was the intended result of this recipe, but I don’t think I care. The texture is amazing and delicious. Sadly, the caramel bottom stuck to the bottom of the pan, but I bet it would be even more awesome with it.

I wasn’t so fond of the flavor, though: heavy doses of nutmeg in my baked goods just make me think of the 19th century, but doesn’t hold any appeal to my modern taste buds. If I were to make this again, I would use apples and cinnamon instead of nutmeg and raisins I would line the loaf pan with parchment, so I could lift the whole thing out without losing the caramel, and I would serve it hot from the oven. In fact, I think I might do just that. I’ll let you know how it goes.

Saturday, October 15th

Alice, or the Scottish Gravediggers: An Evening of Victorian Medicine and Cocktail Bitters.

6pm-8pm @ The Old Stone House, 336 3rd Street, Brooklyn, NY

FREE

Polybe + Seats theater presents a preview of Alice, or the Scottish Gravediggers in part with a bitters tasting with Historic GastronomistSarah Lohman.

Polybe + Seats theater presents a preview of Alice, or the Scottish Gravediggers in part with a bitters tasting with Historic GastronomistSarah Lohman.

Premiering in late October, Alice is an 1829 melodrama about a penniless orphan who works as a maid in her aunt’s inn and is torn between two suitors. She subjects her body to mysterious experiments at a nearby medical school in exchange for treatment for her wounded beloved, a medical student himself. At this event, you’ll get a preview of the play’s gothic set design, music, and art as well as a taste of how Victorian medicine begot the modern cocktail.

Arrive at six for a talk on the link between cocktail bitters and old fashioned medicine. Afterwards, mix and mingle while sipping a bitters-focused cocktail, featuring Original Sin Hard Cider. Then, attend a bitters tasting from local makers, and watch a demo on how to make your own bitters.

Attendees will receive a coupon for discounted admission to the premiere of Alice, or theScottish Gravedigggers.

This event is part of Open House New York and the Historic House Trust Festival Weekend.

Ok. So mine is maybe not the prettiest Baked Alaska. And sometimes, I show my colors as still being a young cook. Like when I dump my carefully crafted dessert all over the floor. Oh well–at least I’m honest about it.

The history of how Baked Alaska came to be is a little loosey goosey, as origin stories for the most famous dishes tend to be. We do know that at the turn of the 19th century, scientists discovered the insulatory properties of egg whites. Cooks seized on this idea, and began creating Baked Alaska-like dishes in the first half of the 19th century. But Chef Charles Ranhofer, the gifted head of the Delmonico’s kitchen, seems to be the one that perfected and popularized it. Allegedly, it was served at a dinner celebrating the purchase of Alaska in 1867, and the popularity of this fantastic new dish sky-rocketed over the next century, peaking sometime in the 1950s.

Making a good, old-fashioned “Alaska, Florida” has a hella lot steps, and the end result doesn’t taste that great. It was waaaay super sweet. I think this is one of those instances when you should look up a modern version of the old classic. The dessert is worth cooking up in a simpler form: the combination of hot meringue and cold ice cream seems like magic and will really impress your friends.

***

Alaska, Florida (Baked Alaska)

2. To Make Banana Ice Cream: Mash 4 banana to a pulp; Mix with 1 pt heavy cream and ½ lb sugar. Stir until the sugar is dissolved. Put into an ice cream maker until frozen soft. Pour, or scoop, into a conical ice cream mold until mold is halfway full. Freeze until frozen hard.

3. To Make Vanilla Ice Cream: Infuse ½ a vanilla bean in ¼ cup milk by gently heating on a stove top burner. Combine with 1 pt heavy cream and ¼ lb sugar; stir until sugar in dissolved. Freeze in an ice cream maker until frozen soft.

4. When banana ice cream is hard, remove from freezer and pour vanilla ice cream over top, until the mold is filled. Return to freezer and freeze until hard.

5. To make meringue: Combine egg whites, remaining sugar, and cream of tartar in the heatproof bowl of electric mixer, and place over a saucepan filled with water. Heat over stove-top like a double boiler, whisking constantly until the sugar has dissolved and the egg whites are warm to the touch, 3 to 3 1/2 minutes. Transfer bowl to electric mixer fitted with the whisk attachment, and whip starting on low speed and gradually increasing to high until stiff, glossy peaks form, about 10 minutes.

6. Preheat oven to 500 degrees. Unmold ice cream, and place on top of cake. Fill a pastry bag with meringue; encase ice cream and cake in meringue

7. Bake in a 500 degree oven for 2 minutes. Serve immediately

***

Be sure to watch the episode to see me demo the whole thing, from start to finish!

I had the most amazing day trip to Philadelphia. Eleven hours of non-stop history nerd fun. Let me tell you about it:

Philadelphians love orange cheese.

First, my beau and I went to the Muetter Museum. It’s an incredible medical history museum that includes everything from a cast of Chang and Eng‘s body to the world’s largest colon. The colon is huge, and upon its acquisition (when the owner of said colon died on the toilet), “2 and a half pailfuls of feces” were removed from it’s interior. How much feces is 2 and a half pailfuls? Well, one giant colon full, of course.

For the rest of this trip, I let Charles Dickens be my tour guide. I have an ongoing obsession with his book American Notes, the tale of his 1842 visit to America. He paints a fascinating image of us as a young, rowdy country, and I’m continually seeking out places that Dickens visited that still exist: like Eastern State Penitentiary.

Opened in1829, Eastern State is the oldest Penitentiary in the world. Dickens admired the Quaker founders’ new approach to decriminalization: prisoners were put into solitary confinement and taught a trade, like wood working, to while away their hours and to give them a skill once they were released. A prisoner had plenty of quiet time to think about what they had done and to make their peace with god. It also occasionally drove people CRAZY.

Later on, the prison went communal, using solitary confinement as punishment for bad behavior.

The prison was in use for a remarkable 141 years; it was abandoned in 1971, and reopened in 1994 for public tours. Originally “Visitors are required to wear hard hats and sign liability waivers.” Today, the prison is stabilized but is in a state of beautiful decay. Restored areas show how it would have looked originally: very pristine and Baptist church-like. We took a guided, hour-long tour of the building and stopped in at a special short tour of the kitchens and dining facilities.

A cell block at Eastern State Penitentiary.

The dining hall at Eastern State Penitentiary

Down in The Hole, and underground facility for solitary confinement. It was flooded from the rain; dark, and miserable.

Next we headed to the Water Works, built in the 18teens , it’s (one of?) the oldest water treatment plant in the States. It’s a restaurant now, but Dickens stopped here when it was functioning to marvel at the modern technology. It’s a lovely piece of architecture. On account of the pouring rain on the day we went, the surrounding river was crazy flooded, making for a very interesting visit.

The rest of the day was spent in consumption: first, we stopped by Reading Terminal Market, a unique collection of food purveyors including Bassett’s Ice Cream. Bassett’s is America’s oldest ice cream company, founded in 1861. I had the Cookies N’ Cream, a favorite of mine from childhood, and my boyfriend had dark chocolate chip and a scoop of pumpkin. Really excellent, extremely satisfying ice cream.

Then we walked over to McGillin’s, the oldest bar in Philly, for a beer. I had the McGillin 1860 IPA; it tasted similar to the house brew at Pete’s Tavern. We sat at the bar and sipped our beers; the crowd was a little sports bar/ college-ee, but I’ve noticed that’s how these ancient bars seem to be able to stay in business. Take, for example, McSorely’s: a NYC institution since 1858, it’s still going strong as a NYU hot spot. Bully for them, I say.

Oldest bar in Philly.

From there, dinner reservations at a restaurant that no history nerd should miss: The City Tavern. The original City Tavern (est. 1773) was an immensely popular and fashionable restaurant in the 18th and 19th centuries, attended not only Dickens, but by most of our founding fathers. The current building is a recreation, with food researched and prepared by chef Walter Staib, who has his own hearth cooking show on PBS.

I was immediately horrified by the attire of the waiters: black 18th-century olde timey outfits. They appeared to be made from polyester and I think they were wearing sport socks. From the neck up, they were entirely modern. I don’t want to be a snob, but I would have rather had my waiters in normal server blacks; I felt the corniness of their dress took away from all the things that were cool about the dining experience.

The menu was fairly typical of restaurants that serve “historical” fair: unchallenging dishes that could have been served in the colonial era, but are prepared in a modern way. Having said that, my boyfriend got a pork chop with mashed potatoes and sauerkraut that was THE SINGLE BEST PORKCHOP I’VE EVER HAD. It was the size of half a pig; had a rich, ham-like flavor from being applewood smoked; and was soo tender it was like meat butter.

Oldhe thymeness

I picked my way through the menu and compiled a historical plate of food. First, I ordered up a sampling of four historic beers–so cool!

Four historic beers.

On the far left was “George Washington’s Tavern Porter: Brewed from a genuine recipe on file in the Rare Manuscripts Room of the New York Public Library.” I found it to be reminiscent of the molasses-based beers Brouwerij Lane brewed for last fall’s Bread & Beer event. I was stoked to try it since I had missed Coney Island Brewing Company’s recreation for the Library’s 100th anniversary. Next was “Thomas Jefferson’s 1774 Tavern Ale: Thomas Jefferson made beer twice a year. Our version of this ale is made following Jefferson’s original recipe…” I found it to be floral and pleasant, my second favorite of the four. The next was “Poor Richard’s Tavern Spruce: Based on Benjamin Franklin’s recipe, written while he was an ambassador to France.” This beer was better than any attempts I’ve made with spruce based beers, but it was still too dark a beer for my taste. The last beer was my favorite, “Alexander Hamilton’s Federalist Ale: In the style of the common man’s ale…” It was excellent and tasted almost exactly like the Common Ale Pete made over the summer.

I ordered a bowl of Pepperpot Soup, a Revolutionary War-era favorite imported from the Caribbean. The menu said it was made with “beef;” but actually it’s beef tripe. I’ve had some bad experiences with tripe in the past, but the soup was delicious, although very, very peppery.

And for my main course, I chose the only entree that included a historical note: “Fried Tofu – In a 1770 letter to Philadelphia’s John Bartram, Benjamin Franklin included instructions on how to make tofu. Sally Lunn breaded fried tofu, spinach, seasonal vegetables, sauteed tomatoes & herbs, linguine.” No shit! Here’s Franklin:

“…Chinese Garavances, with Father Navarretta’s account of the universal use of a cheese made of them, in China, which so excited my curiosity, that I caused inquiry to be made of Mr. Flint, who lived many years there, in what manner the cheese was made; and I send you his answer. I have since learnt, that some runnings of salt (I suppose runnet) is put into water, when the meal is in it, to turn to curds.”

And the recipes he procured:

1st Process

The method the Chinese convert Callivances into Towfu. They first steep the Grain in warm water ten or twelve Hours to soften a little, that it may grind easily. It is a stone Mill with a hole in the top to receive a small drain of warm water which passes between the two Stones the time of grinding to carry off the flower from between & keeps draining into a Tub which has a Sieve or Cloth at the top to stop the gross parts from mixing with the flower.

2d Process

Then they stir up the flower & put the Water over the Fire just for it to simmer, keeping stirring till it thickens & then taken out & put into a frame that has a Cloth which will hold the Substance, & press the Water from it, & when the Water is gone off the Frame with the Contents with a Weight on it must be put over the Steam of boiling Water for half an hour to harden or something longer. The pressing & boiling over the Steam brings it into the Form you see it carried about at Canton. This is the process as I always understood.

(Thanks to Lord Whimsy for printing this text, originally found in the 1849 printing of Bartram’s letters.)

Colonial "Towfu"!

Afterwards, we stopped by the Franklin Fountain, another of the the new-breed of old-school soda fountains. I eat a lot of ice cream, but this place has the best sundaes I’ve ever had. If I lived in Philly, I would go here all. the. time.

My favorite sundae ever! Rocky road ice cream, peanut butter sauce, and pretzels! AAAAAAH SO GOOOOOD!

Interior of Franklin Fountain.

House-made syrups for handmade sodas.

Such a wonderful day. More photos on flickr.

The first “gaspacho” recipe, from 1824.

The first “gaspacho” recipe, from 1824.Yesterday I appeared on Heritage Radio Network’s We Dig Plants, the bawdiest horticulture show on the web. This past Sunday’s show was all about tomatoes, and I popped on as a special guest to share some historic tomato recipes. You can listen to the whole show here.

I brought along a few tubs of gazpacho I made from an 1824 recipes. They were crazy delicious (I saved the leftover for my lunch today). Mary Randolph’s The Virginia Housewife, published in 1824, has some of the earliest tomato recipes in print, and the first gazpacho recipe printed EVER on the planet. At least that we know of. The directions are pretty self explanatory, so here is the original recipe.

I did not stew and make my own tomato juice, I found this great, strained, tomato puree in a box at the store. The gazpacho was more like a cold, fresh salad, and was really wonderful. Carmen, one of the show’s hosts, even took some home to her tomato-hating husband in hopes that it would turn him into a tomato lover.

I also showed up with Bloody Marys–or, more accurately, Red Snappers, as they were originally known. When the drink was created in the 1920s, vodka wasn’t yet widely available in the United States; the liquor of choice was gin! The recipe for the Red Snapper, from the King Cole Bar at the St. Regis hotel in New York, is below. I actually prefer the gin over vodka; I would recommend Hendrick’s gin; the cucumber notes compliment the tomatoes beautifully.

***

The Red Snapper

From the St. Regis Bar, 1920s

1 1/2 oz Gin

2 dashes Worcestershire sauce

4 dashes Tabasco sauce

Pinch of salt and pepper

1/4 ounce fresh lemon juice

4 ounces tomato juice

Combine all ingredients in a glass and shake or stir to mix. Serve chilled.

***

Both of these recipes are great if you need to use up a tomato surplus; For more history on both of these recipes, listen to the entire radio show here!

And on a somewhat unrelated note, I attended my first “crawfish boil” yesterday at the Brooklyn Brainery’s Summer Explosion. I was all geared up to eat my first crayfish, but the sight of their yellow guts spilling out of their exoskeletons turned me off. I don’t do well with invertebrates. Instead, I stuffed my face with peach cobbler.

Ilana Kohn snapped this photo at my Gin in June event last month, showing our steady progession through the history of gin.

We started with Genever, the Dutch alcohol that gave birth to modern gin, in one of the most primitive cocktails: the gin sling. Next we moved through time to a gin popular in the late 19th century, Old Tom. It’s slightly sweet and less herbal than a Genever, but more so that a London Dry–the evolutionary link between the two. We sampled it in a Martinez cocktail (the predecessor of the modern Martini), which is also where the Boker’s bitters went. Then, we moved to a locally produced dry gin, Breucklen, in a cocktail from another burough, the Bronx.

Last, we sampled an old style gin that’s only recently come on the market in America, thanks to the crafty distillers of DH Krahn: Averell Damson Gin, a herbaceous gin infused with tart plum juice. The cocktail was served was of my own creation, inspired by an 1832 recipe for a Sloe Gin Fizz. To get the recipe for the Damson Fizz Punch, go here. I did a guest post on it for Cocktail Virgin Slut because the drink is so perfect for summer.

A carefully crafted rye cocktail from Stoddard's Fine Food and Ale. Notice the breathtakingly beautiful, hand-carved lump of ice in the center. That is some pretty ice.

Since I’ve been on a month- long hiatus from the blog, I figured I should let you know what I’ve been up while I’ve been gone! First, I’d like to share some images from last weekend’s Boston 19th Century Pub Crawl.

We began the night at Eastern Standard Kitchen & Drinks. I sipped on a Root of All Evil cocktail, a blend of coconut and an amazingly subtle and complex root beer liquor. It was delicious-one of my favorite cocktails of the night!

The crowd mixes and mingles at Eastern Standard.

Stoddard’s Fine Food and Ale had us enter via the “speakeasy” entrance. The building was built in the 1860s and the entire block is historic. The result was a twisting, turning, increasing shady back alley that suddenly opened up into Stoddard’s. Completely awesome and fun.

A snapshot of the bar at Stoddard’s. The have an amazing list of historic cocktails available every day. To add another degree of authenticity, the bartenders carve off chunks of this giant ice block to make the cocktails. In addition to the rye drink pictured at the top of the post, I had a slammin drink called the Temple Smash: rye, ginger ale, mint, and seltzer. Fav.

Rich poses as our logo.

Waiting to get into the final stop of the evening, Drink.

Cocktail Virgin Slut joined us on the crawl; here, he takes notes on an adorable little cocktail at Drink.

The night ends with a bang: the skilled bartenders at Drink mixed me a Blue Blazer. I had never in my wildest dreams imagined there was a bar with two silver tankards ready to go at a moments notice. To be honest, to have one made for me made me feel like a god. Drink also mixed up an amazing classic punch, in a giantic bowl. The night ended well.

An article in a local rag, Edible Manhattan, told the story of New York’s markets of old. The article focused on Washington Market, which was on Manhattan’s lower west side. Apparently the abundance was incomparable and was cataloged by a man named Thomas de Voe, a butcher who worked his way up to be head of the market (read the whole article here). His book, published in the 1860s, the Market Assistant, contains a brief description of “…every article of human food sold in the public markets of New York, Boston, Philadelphis, and Brooklyn.” Among those articles of food, Moose Snout.

De Voe says of the moose: “There is no doubt but the flesh of the tame male either moose or elk, when castrated, could be converted into a dish which the epicure could not resist. The tongue is considered a delicacy, as is also his moufle, the large gristly extremity of its large nose, when properly prepared and cooked. The skins are much used by the hunters for snow shoes and moccasins; for these purposes they are best when taken in the month of October. Mr Wm Paul had when I saw him on the 7th of February, 1856, in Fulton street New York near the Washington Market, nine moose and two elk which he had brought from Iowa. They were in good condition although killed some five weeks before.” (1867)

An article, from Shield’s Magazine, 1905, says something on the way to prepare a moose noose: “One does not necessarily have to go to the woods for venison; Moose and caribou steaks are far better for hanging several days, but some of the choicest morsels of the moose and the caribou are unobtainable far from the woods where the animals live. The nose, the liver, and the kidneys though highly esteemed by hunters, are never brought to market. Moose nose in particular is an exceptional delicacy. The nose of the caribou, though also good, is much inferior to the other, being full of small bones. Moose nose resembles beaver tail in this respect, that it possesses a delightful flavor distinctly its own and scarcely comparable with anything else. What makes it all the rarer is that it is not only necessary to kill a moose in order to obtain the delicacy, but also to destroy that most beautiful and most highly prized trophy of the chase: a moose head. You cannot eat the nose and have the head too. To prepare the nose for the table, it is cut off the animal as soon as the latter is killed and is then scalded and scraped to take off the hair. Then it is slightly smoked and boiled. ”

I have seen modern reference to jellied nose as well as moose nose soup. I’m on the look-out for a moufle.