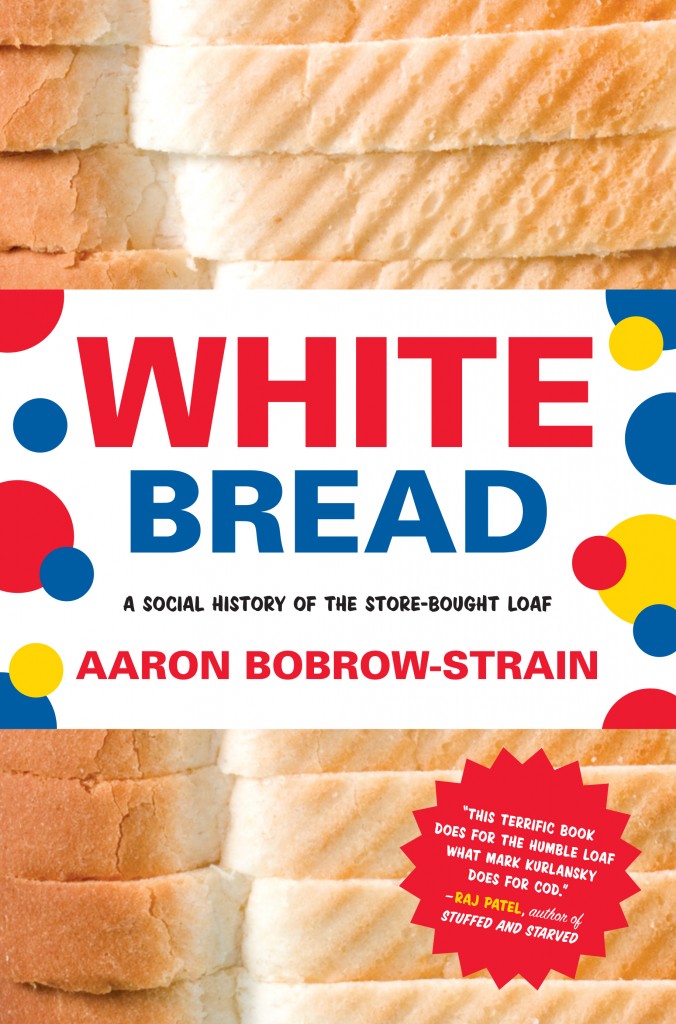

The Manila Restaurant on 47 Sands St, Brooklyn, NY, 1938. This photo used to be available for licensing through NYC.gov, but I can no longer locate it. So here it is in all its watermarked glory.

This article is one of a series I’m writing as a Visiting Artist at BLDG92 in the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

I’ve always found that immigrated cuisines are best eaten at hole-in-the-wall type restaurants, for the most authentic experience. But in my attempts to try authentic Filipino food, the hole-in-the-wall my husband and I found ourselves standing in front of was closed–permanently. So a quick Google search for other restaurants in the area led us to not another Filipino restaurant, but a Filipino Gastropub.

It was fancier than I had wanted, but when my husband and I cozied up to the bar, I noticed that the menu included a dish that four people had insisted I try: balut.

“What is it?” I asked the bartender. After he explained it, I ashamedly admitted “I don’t have the strength.”

But that wasn’t true of the gentleman sitting next to me. A Filipino immigrant, sitting with his wife and grown son, he ordered his balut and the staff let out a loud whoop! of celebration.

“All this yelling for an egg??” his wife asked in laughing disbelief. Balut is a fertilized duck egg: you crack the egg to find a half-developed bird fetus, swimming in briny broth.

“It’s a special dish,” the bartender replied, smiling. Then, to the husband: “Do you remember it from the Philippines?”

“Yes, I miss it!” he replied, in a way that nearly pained him, pressing his hand over his heart. “I ate it all the time. I sip the broth first, then eat the meat–such delicate bird meat!”

Food gives comfort when we long for home. It’s all the good parts of where we come from and none of the reasons why we left. This is as true today as it was in the 1930s, when a thriving Filipino population found their home just outside of the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

The Phillipines fell under American occupation shortly after the Spanish-American war. The result was an increased American military population on the islands, but also an increase in Filipino immigration to the United States. Many young Filipino men joined the Navy, for economic opportunity as well as adventure, particularly as the nation geared up for World War II. Many of these recruits ended up at the Brooklyn Navy Yard; by the 1940s, The Navy Yard had over 70,000 employees, and was a key military base and constructed such infamous ships as the USS Missouri.

Washington Street & Sands Street, 1930. Source.

With so many employees in the yard, the population of the Brooklyn neighborhoods surrounding the Yard exploded. At the end of a workday, or over a weekend of leave, A Filipino sailor could stroll out the Sands St. exit; he’d bypass the American lunchrooms and bars and head for the intersection of Sands and Washington Streets, where he could find Brooklyn’s Filipino community and a taste of home.

In 1939, WPA writers produced a guide book to every nook and cranny of New York City’s five boroughs; one intrepid writer recorded the area around the Navy Yard and its Filipino community:

Around Sands and Washington Streets is a colony of Filipinos; native food, extremely rare in the eastern part of the United States, is served in a Filipino restaurant at 47 Sands Street. Among the favorite dishes are adabong gaboy (pork fried in soy sauce and garlic); sinigang isda and sinigang visaya (fish soups); mixta (beans and rice), and such tropical fruits as mangoes and pomelos, the latter a kind of orange as large as a grapefruit.

A photo from 1938 lets us peak inside and glimpse a night filled with familiar food, music and friends. The Manila restaurant was probablly the first Filipino eatery in the city, having been established since at least 1927. It looks like a good place, the customers are relaxed, and you can just barely make out a menu hanging on the back wall. An ad for the restaurant, uncovered by Purple Yam and Dawn Bohulano Mabalon, Assistant Professor of the History Dept at the San Francisco State University, says the restaurant serves “Philippine, American, Chinese, and Spanish dishes.” A sign of creeping Americanization, or of the diversity of Filipino culture?

No mention of balut, though. I bet those in the know could ask for it.

Today, immigrants from the Philippines account for 4% of the foreign-born population in the United States; only Mexico, China, and India send more of their sons and daughters to make a new life in this country. There are easily a dozen Filipino restaurant in the city now, and probably many more, tucked away in the right neighborhoods, offering a little bit of comfort to those far from home.