Many flavored egg creams from the Brooklyn Farmacy. Recipe below.

Many flavored egg creams from the Brooklyn Farmacy. Recipe below.

Photograph (c) 2014 by Michael Harlan Turkell.

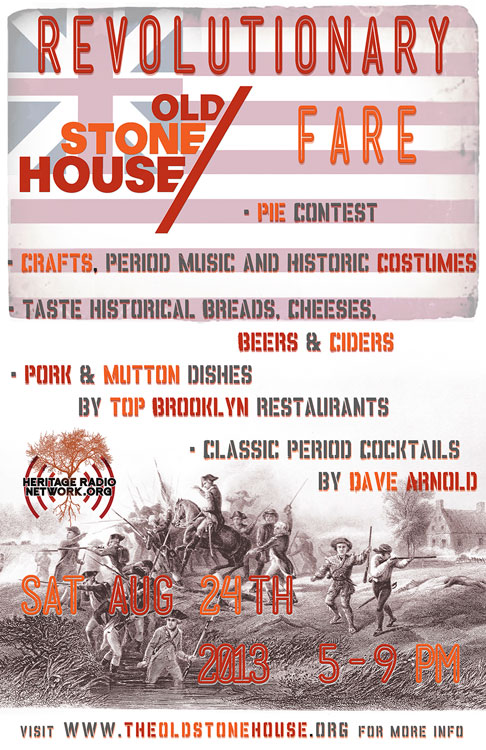

Today we have a guest post from Elizabeth Kiem, a writer who helped research The Soda Fountain: Floats, Sundaes, Egg Creams & More–Stories and Flavors of an American Original by Brooklyn Farmacy & Soda Fountain founders Gia Giasullo and Peter Freeman. The book contains over 70 recipes for updated soda fountain classics like egg creams and milkshakes using seasonal ingredients. There’s also a hearty helping of the history and the stories behind the drinks–like the nugget below!

Joseph Priestley is the founding father you never heard of. A chemist, educator, linguist and philosopher, Priestly was a real poster child of 18th Enlightenment. But he was also the proud papa of 18th century Effervescence.

Joseph Priestley is the founding father you never heard of. A chemist, educator, linguist and philosopher, Priestly was a real poster child of 18th Enlightenment. But he was also the proud papa of 18th century Effervescence.

That’s right. Joseph Priestley, a dead white guy who’s right at home among the stocking-legged, powder-haired, long-nosed Constitution signers, is a true Founding Father … of the American soda fountain.

You’d have to call him an immigrant since he didn’t cross the pond until 1791, but when he did, it was in classic fashion: he was fleeing persecution back in England where his small-minded neighbors had ransacked and burned his home and laboratory.

His sins?

Well, Priestley criticized the church, fraternized with revolutionaries (Jefferson wrote regularly; Ben Franklin called him “an honest heretic”) and had been impregnating water for years. If that sounds mildly ludicrous today, in the 18th century it was wildly reckless. Priestley, after all, discovered “dephlogisticated air,” a.k.a oxygen. And that’s a dangerous thing to throw on the fire. But “impregnate” water with it and voila, you have carbonated water.

The attack on Priestley’s home! (source)

The attack on Priestley’s home! (source)

The first thirty souls to enjoy the fruits of Priestley’s impregnations was the crew of Captain James Cook. The self-taught scientist had hoped to join the famous explorer’s second voyage to the South Seas as the resident astronomer. That didn’t pan out, but Cook took barrels of Priestley’s impregnated water on the HMS Resolution when it sailed in 1773. Refreshing stuff – soda water in the South Seas –even if it doesn’t (as Priestley had boasted) prevent scurvy.

So here’s to the founding father you never knew. Joseph Priestly, the discoverer of oxygen and creator of soda water. We owe a great debt to his rational politics, his scientific reason, his theological dissent … and his bubbles.

Now let’s put that impregnated water to use.

***

BROOKLYN EGG CREAM

From The Soda Fountain: Floats, Sundaes, Egg Creams & More–Stories and Flavors of an American Original

1⁄4 cup plus 2 tablespoons (3 ounces) cold whole milk

3⁄4 cup (6 ounces) plain cold seltzer

3 tablespoons (11⁄2 ounces) Fox’s U-Bet chocolate syrup

Pour the milk into an egg cream glass and add seltzer until froth comes up to the top of the glass. Pour the syrup into the center of the glass and then gently push the back of a spoon into the center of the drink. Rock the spoon back and forth, keeping most of the action at the bottom of the glass, to incorporate the syrup without wrecking the froth. Serve immediately.

Reprinted with permission from The Soda Fountain by Brooklyn Farmacy and Soda Fountain, Inc. copyright (c) 2014. Published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Random House LLC.

***

For more history, read about the egg cream adventure Elizabeth, Gia and I went on last year. The Soda Fountain: Floats, Sundaes, Egg Creams & More–Stories and Flavors of an American Original goes on sale TODAY! To buy a copy, go here

!