The origins of Apple Pan Dowdy are shrouded in mystery. Undoubtedly related to crumbles, slumps, and crisps, the recipe I decided to feature in my Edible Queens article comes from a cookbook published at the same time as the 1964 World’s Fair, The American Heritage Cookbook. However, the first time I’ve been able to find the dessert in print is in Miss Corson’s Practical American Cookery, published in 1886. Her version is a much juicier than the ’64 recipe, a juice the soaks into the pie crust top and begs to be licked off the plate. After I devoured the dessert, I poured this juice from the bottom of the baking dish and cooked it down into a syrup which I served atop vanilla ice cream. Oh god so good!

The temperature is going to be pushing 100 here in NYC on Independence Day, so I know that last thing you want to do is heat up your oven and bake. In fact, I doubt the legitimacy of this dish as an 18th century July Fourth favorite–considering not only the summer heat, but why would you use last year’s old nasty apples to bake when so much fresh fruit abounds in July? However, this recipe is a great way to use up extra pie crust. Pieces of crust are strewn across the top, then “dowdied” by pushing them into the baking apples; the crust absorbs the juices and becomes soft and biscuit-like. And it is delicious; so if you have air conditioning, I say bake away.

***

Apple Pan-Dowdy

From Miss Corson’s Practical American Cookery by Juliet Corson, 1886.

5 large baking apples

1 tsp. cinnamon

1 tsp. salt

1 lb light brown sugar (about 1 1/2 cups)

1 c. cider

1 nine-inch pie crust, store bought or homemade

1. Preheat oven to 325 degrees.

2. Mix together sugar, cinnamon, and salt. Peel and core apples and cut in to ¼ inch thick slices; mix with lemon juice to prevent browning. Toss with the sugar and spices and pile into the baking dish. Pour cider over apple mixture.

3. Cover apples with pie crust by weaving together wide strips, or by simply scattering torn pieces of crust over the top. Bake at 400 degrees for one hour. Serve hot or cold with a dollop of whipped cream.

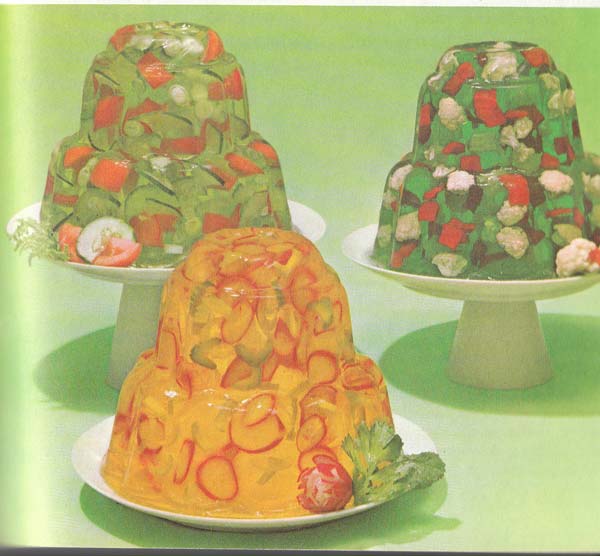

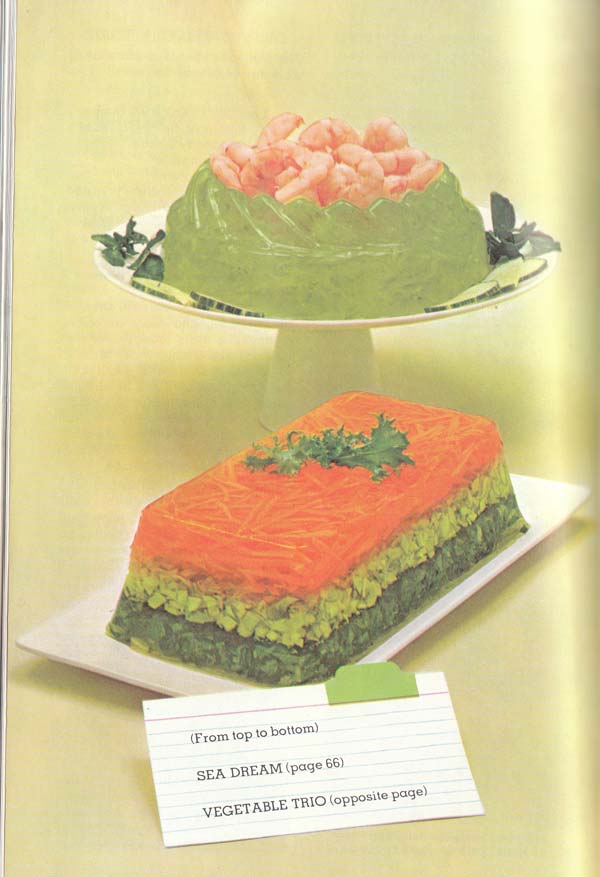

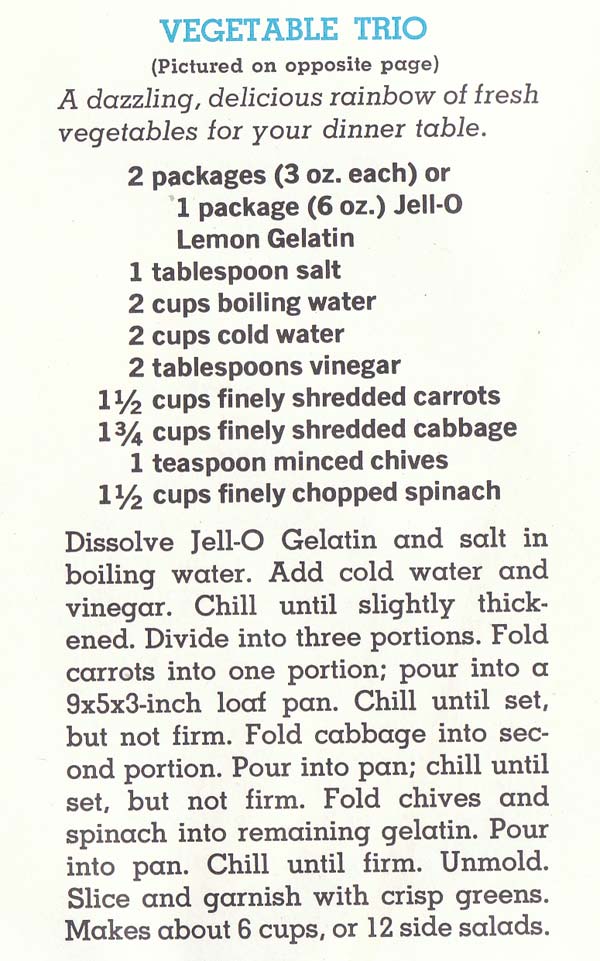

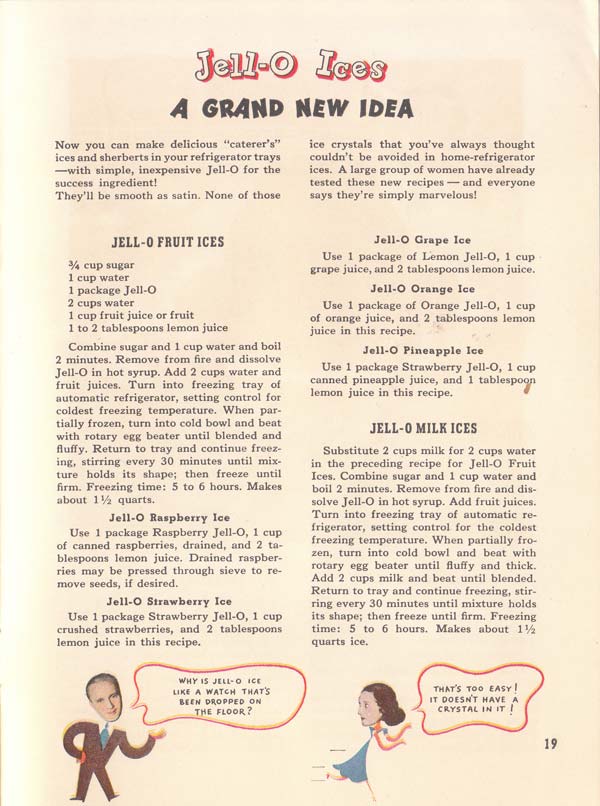

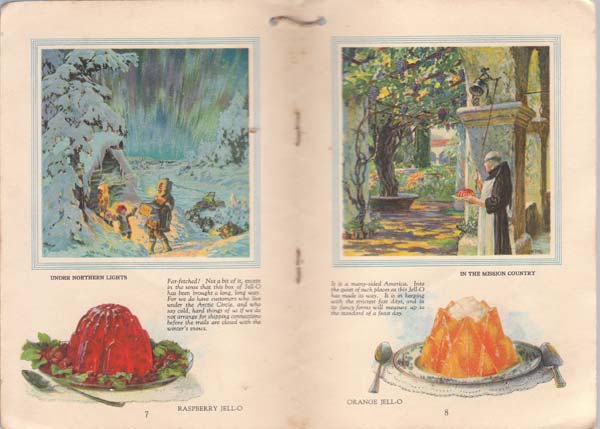

I decided to start off the week with something appealing, and refreshing– I want to strike a balance between the horrors of Jell-O, and some ideas that might be innovative and delicious.

I decided to start off the week with something appealing, and refreshing– I want to strike a balance between the horrors of Jell-O, and some ideas that might be innovative and delicious.