Long Island’s Wolffer Estate Verjus, a tart coking ingredient made from the juice of unripe grapes.

Long Island’s Wolffer Estate Verjus, a tart coking ingredient made from the juice of unripe grapes.

This is the third is a series of posts I’m doing about Medieval cooking; I’ve already eaten dishes from the earliest known English cooking manuscript; and dabbled in Martha Washington’s historic recipes; now, I want to focus on an interesting medieval ingredient: verjus, verjuice, or literally “green juice.”

The History

A byproduct of the wine industry, grape vines are thinned midway through the season, producing a haul of unripe grapes which can be pressed for their juice. Before lemons were imported into Northern Europe after the crusades, verjus added sour and acid flavors into food. Tartaric acid, better known as cream of tartar when used in baked goods, is responsible for its flavor; poured over ice and drunk straight, verjus is a refreshingly tart grape juice. I’ve read it can also be pressed from windfall apples and other unripe fruits and can be bottled and kept for up to a year.

Winemakers are trying to reintroduce verjus to a contemporary market; I found my bottle in a cheese shop, Formaggio Essex, on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. The New York Times wrote about verjus in 2010, suggesting it as ideal for saucing up a chicken (also a very traditional use) and replacing the lemon in “lemon bars” with verjus, for a dessert.

I scoured the internets for period-appropriate verjus recipes, and cooked up a dinner party to taste test the results!

The Recipes

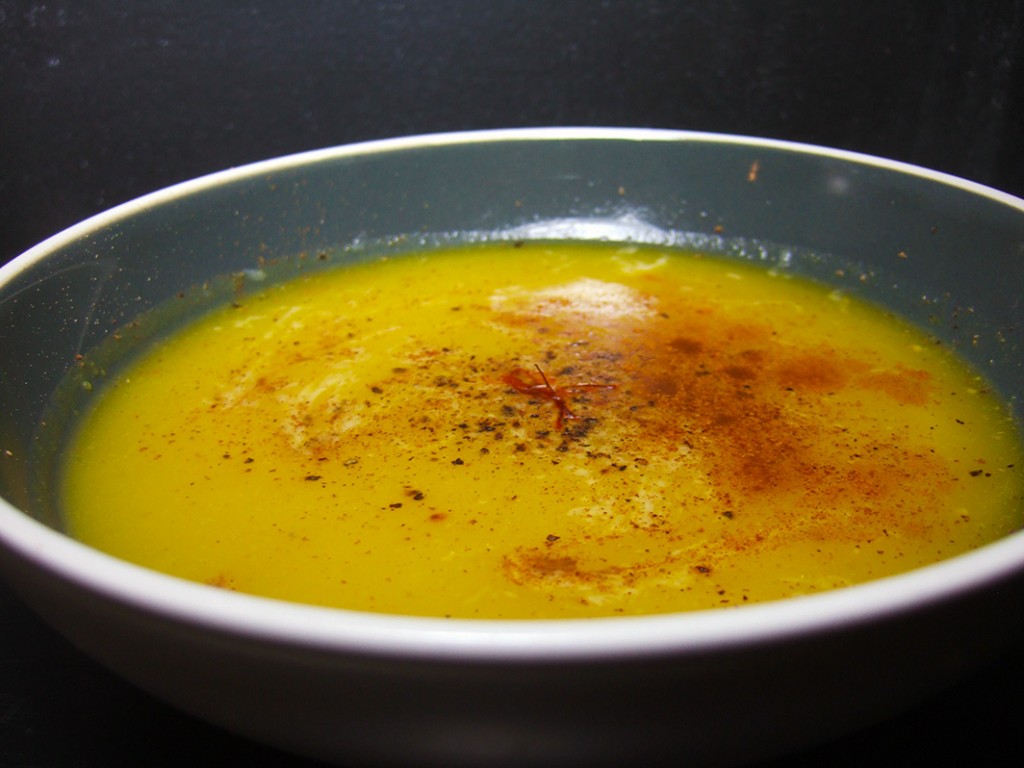

I hosted my dinner on a Friday night, so I decided to a go a little Medieval-Catholic-ee and observe a “fast day,” meaning no meat. All my offerings were veg, starting with a squash soup from Libro de Arte Coquinaria (The Art of Cooking) written c. 1465 by Martino da Como.

A Squash or Pumpkin Soup, 1465.

A Squash or Pumpkin Soup, 1465.

The translated recipe for this dish can be found in The Medieval Kitchen: Recipes from France and Italy. I used two butternut squash, sliced and cooked in a homemade vegetable stock that was heavy on the onion. I pureed to softened squash, and blended it with egg yolks, grated asiago cheese, and saffron. I plated each serving with a tablespoon of verjuice, and topped it with two kinds of black pepper, cloves, fresh grated nutmeg, and a dash of cinnamon. My diners were pleased with the recipe: they loved that the results were lighter and less sweet than a typical, contemporary squash soup. Get the full recipe here.

On the side, I served Green Poree for Days of Abstinence, a medieval French recipe of chard cooked with verjuice and finished with butter. I had picked this recipe to round out my menu, but this simple dish ended up being the favorite of the night. The verjus made the slow-braised Swiss chard sweet and bright. Everyone agreed it was not only the best Swiss chard they had ever eaten, but it was also a pleasure to eat: even my husband cleaned his plate.

Swiss Chard with Verjuice: The Best!

Swiss Chard with Verjuice: The Best!

Swiss Chard Braised with Verjus

Adpated from The Medieval Kitchen: Recipes from France and Italy

This recipe is enough for one head of swiss chard, which would feed 1-2 people. I recommend preparing one head of chard per person; it cooks down substantially.

1 head Swiss chard, washed, dried, and tough stems removed.

1/4 cup verjuice

1/2 cup vegetable stock

2 tablespoons butter (or to taste)

Salt (to taste)

In a large pot, add chard, stock, salt and verjuice. Bring to a boil, then reduce heat to low and simmer 20-30 minutes until tender. Stir in butter and serve with toasted bread.

Verjuice dessert bar.

Verjuice dessert bar.

For dessert, I took the New York Times’ suggestion and baked Ina Garten’s Lemon Bar recipe, replacing the lemon juice with verjuice. I wasn’t sure if I should still add the lemon zest, however. I didn’t and I found the results to be too subtle and flavorless. Most of of diners enjoyed the slightly tart taste of the custardy bars; I took the leftovers to a party, and everyone gorged themselves. By the way, when making this recipe, I realized I didn’t own a 9×13 pan, so I dumped the batter in a much smaller pan and told myself it would be fine. As a result, the extra thick verjus bars didn’t set properly in the middle, and were a bit runny when I sliced into them. But thems the breaks, and no one seemed it mind.

The Results

Verjuice is awesome. I would buy it and try it again; I would even attempt to make it myself after I move out of New York have some outdoor work space. I think it’s a great thing to keep in the kitchen and I’m really curious to try it to deglaze pans and make sauces for meat. I’d love to use it with more cooked vegetables; I think the flavor complements greens better than lemon juice. And one of my dinner guests pointed out it would be a great mixer for drinks; she envisioned gin, which would make an excellent summer cocktail.

If you’re interested in giving verjus a try, there is an entire cookbook devoted to Cooking with Verjuice. You can also buy it online

if you haven’t seen it in any nearby stores.

The possibilities are endless. The flavor is incredible (even if you hate grape juice, like I do!). Try it.

I am now inspired to try verjus. But…how could a squash soup be included in a book from 1465? It’s a New World food, so it would have been up unknown in pre-Columbian Europe.

Totally. I had the same conversation with myself. But I had some remembrance that there was a native European squash. I knew it wasn’t a butternut squash, but I was simply curious to try verjuice in a variety of recipes as opposed to going for complete historic accuracy. However, the butternut soup was the most mediocre of the recipes, and based on Kate’s descriptions of the real thing, it sound like it would have made a much better soup.

It’s great stuff, isn’t it?

In England they also made verjuice with crabapples, something I’ve always wanted to try to do it but think it would be a big deal since crabapples are not really juicy… I imagine it would take a barrel to make a small amount! Anyone with a crabapple, this is the time of year to do it.

I would love to try that. My family has both crab apples and a bunch of pippins on their property. Someday I will build a press and try to make my own verjus. They even have wild grapes, which I bet would also be great.

Mara, it’s probably a gourd soup. Lots of redactions translate what should be “gourd” as “squash” because (1) moderns like squash and (2) eatable gourds are a little hard to find these days.

Are you familiar with Duke Cariadoc’s Miscellany? His research shows that any pre-1492 recipe said to have “squash” in it probably really used Italian Eatable Gourd (aka white-flowering gourd). You can get seeds for this plant from online catalogs, if you want to grow it, but Cariadoc says he found what he thinks is probably the right squash in a Chinese market: it’s called “opo.” He says it tastes something like zucchini but less bitter.

Now I am super intrigued! I’m going to keep my eyes open in Chinatown. look for opo, coming soon to this blog…

Found some info on foodtimeline.org. Asian gourds would have been available–

If pumpkins are a “New World” food, why are they sometimes listed as ingredients in Medieval European recipes? If you notice, these references are usually found in Medieval cooking books with modernized recipes. The original recipes simply call for squash or gourds. Why substitute pumpkin? Some Medieval recipes for members of the curcurbit family (gourds, calabash, cucumbers, melons) are more palatable to contemporary tastes if you make them with pumpkin. It’s also readily available.

“3. Winter Squash or Pumpkin Soup…The curcurbits are a large, rich family including cucumbers, melons, and squashes. But the Old World knew neither the winter squash (Curcurbita pepo) nor the pumpkin (Curcurbita maxima), both of which were brought from the Americas. If we can trust the title of the recipe, Congordes, and if we think of the depictions of squash (zucche) harvests in the many manuscripts comprising the Tacuinum sanitatis–a medical treatise of Arab origin that lists the medicinal properties of various foods–the cook is probably dealing here with gourds (Lagenaria vulgaris). These came originally from southern Asia, and were well known in Western Europe in the Middle Ages. But without fresh gourds to hand, you can prepare this soup with winter squash or pumpkin.”

—The Medieval Kitchen: Recipes from France and Italy, Odile Redon, Francoise Sabban, & Silvano Serventi, translated by Edward Schneider [University of Chicago Press:Chicago] 1998 (p. 55-6)

I’m not positive, but I think “pumpkin” was used for Old World gourds before the New World gourds came in.

I love verjus and often sub it for vinegar or white wine, depending on the recipe. My little vineyard doesn’t put forth enough fruit for me to make it at home, but I want to!

It is pretty fantastic. It’s a lot more expensive than vinegar, but the flavor is so unique without being overpowering.

You can get sour grape juice at a Middle Eastern grocery store, and it costs a lot less than verjuice from a gourmet store.