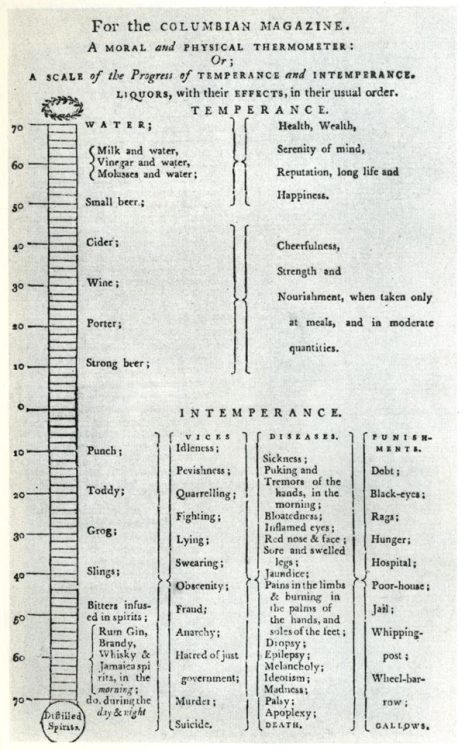

Dr. Benjamin Rush’s “Moral and Physical Thermometer,” published 1789

What am I up to? Read this introduction to understand the plan.

8:30am:

I have to start my day by “taking my bitters.” Bitters, infusions of herbs in spices in high proof alcohol, started out as health tonics. Starting the day with an “eye-opener” of spirits, water, sugar and a healthy dose of bitters was not only considered socially acceptable, but good for you. In fact, the first drink to ever be called a “cock-tail” was exactly this concoction, using whiskey for the spirit. And that’s how I’m started my day today, using an 1833 recipe for the original cocktail, as it appears in David Wondrich’s book Imbibe!: From Absinthe Cocktail to Whiskey Smash

1 tsp sugar

2 oz whiskey

3 oz water

4 dashes bitters

Nutmeg

Muddle sugar with water until dissolved. Add whiskey and bitters. Stir. Top with grated nutmeg.

I grabbed the first whiskey I saw in the liquor cabinet, which was Old Crow. Only after I made my drink did i realize we had a Buffalo Trace corn whiskey, that would have been more period appropriate because it was un-aged.

My boyfriend demanded to join me from under the comforter on the bed. I fixed him a drink, and he sat sleepy-eyed on the edge of the bed holding it.

“Well, what are you going to do now that you’re awake and drinking bourbon?”

“I don’t know…vomit?”

Running Total: 2 oz of hard spirits consumed @ 80 proof

8:51 am:

I realized I made our drinks with one oz of water instead of three. Whoops. So we are just drinking bourbon on an empty stomach.

9:38 am:

Had a tankard of hard cider with breakfast (eggs, bacon, toast). John Adams, an ardent temperenace supporter, had a tankard of cider with breakfast every morning. It wasn’t cider, beer, or wine that was considered “alcoholic,” it was distilled spirits considered ruinous to the working man (see above chart).

Cider was the American drink–scholars believe that Americans consumed more alcohol through hard cider than the much more potent spirit, Rum. The desire for hard cider didn’t subside until the temperance movement convinced many farmers to cut down their apples trees. Thankfully, events like Cider Week are bringing attention back to New York State growers and distillers.

11 oz of hard cider @ 10 proof. Running Total: 3 units of alcohol.

Yes. I’m a little drunk. Time to take a shower and get some work done.

11 am:

It is now the “elevens”!!! The Colonial American version of a coffee break! A hot toddy is appropriate at the elevens when the weather is cold, so I’ve decided to make apple toddys, one of the first cocktails to be recorded in print. I baked apples with “apple pie spice”, sugar and butter; then added them to hot water and apple brandy. I used apple brandy from Warwick Valley Winery, and from Laird’s who received the very first distiller’s license after the Revolutionary War.

I have not managed to take a shower yet. Let’s be honest here: if colonial Americans drank like this every day, their tolerance would be quite high. I will be drunk, but the Common Man in 1780 would have just been getting started.

I am trying to drink a glass of water between every drink.

2 oz of apple brandy @ 80 proof. Total: 5 units of alcohol in 2.5 hours.

11:40: am:

Where has the time gone? I have still not showered. I know I am drunk because everything is a celebration: “yaaaaay! It’s time to water the plant!!!”

12:22 pm:

Trying to sober up a little before lunch. IN the meantime, there was an interesting thread on Facebook yesterday regarding Colonial drinking, and I wanted to share some of the highlights.

R: All I can say is that I’d hate to be Sarah the morning after tomorrow! They also drank fortified wines (in 18th and 19th centuries) which get you crazy-drunk. I’ve heard a lot of people say that everyone drank ale, even children, because the water wasn’t potable. That may be true if you got your water from Collect Pond, but rich people would have had their own wells. I think they just liked tying one on.

Me: I don’t buy the “safer than water” excuse. In NYc — possibly. But the rest of the country was not so densely populated, and America was known for good quality water. That’s why everything we brewed/distilled was so delicious! I think the bottom line is grain and apples are worth more as liquor; and this is also a time when we had little else to drink but water. Alcohol provided variety, that today we replace with soda and fruit juice. Also true about the beer–but it was brewed at home, and only slightly alcoholic. More like today’s fermented sodas.

D: That’s a good point about water availability in America. But I wonder if the prevalence of cider was partly a continuation of European standards, though. In Europe, there was very little clean drinking water, so people might have just thought that alcohol was healthier than water. And even in New World, a lot of clean streams wouldn’t have stayed clean for long once settlers arrived.

Me: I think it’s a myth. I think it has more to do with financial reasons. Grain and apples go bad. Spirits and cider not, and you can sell the latter for more than the former.

D: Is there anything we know about what the colonists *did* think about nutrition, including the nutritional aspect of booze? I mean, there must have been some as-far-as-they-knew medical knowledge and folk wisdom about what foods you had to eat in order to be healthy. Did they think of spirits as having some kind of common nutritive properties with grain, such that one was a decent substitute for the other?

Me: I don’t know a ton about the topic, but I do know that “small” beer (home brewed, weak), cider, and wine were considered healthy, nutritive drinks that brought wealth and happiness, while distilled spirits would be the ruin of the working man. Dr Benjamin Rush was an early temperance advocate, and he made this great chart of what will happen to you if you drink various alcohols in various quantities (see above).

Thoughts?

1:19 PM:

I’m hungover and its painful.

2:11 PM:

Managed to get to the grocery store for more cider and a DiGiorno pizza. The lady at the store wished me a happy birthday (it’s the 15th) and I responded “You too!”

Having another cider with lunch. Here’s my line up for the rest of the day:

Throughout America, early afternoon dinner was accopanied by hard cider or distilled spirits mized with water; in later afternoon came another break; then supper with more refreshment. Finally, in the evening it was time to pause and reflect upon the day’s events while sitting by the home or the tavern fireside sipping spirits. (The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition

, W.J. Rorabaugh)

Ugh. My head hurts.

12 oz of cider @ 10 proof. Total: 6 units of alcohol in 6 hours.

4:13 pm

After my last hard cider, my boyfriend and I sat down to watch The Brave Little Toaster. We promptly fell asleep. Now that I’m awake, I’m clearly sober, clearly hungover, and I have a sickening migraine.

To be honest, I’ve walked this weird tightrope between sobriety and drunkeness all day. Consuming so much alcohol so early in the day, on an empty stomach, is a surprsingly unpleasant feeling. It’s honestly not what I expected. I thought since the alcohol was spread out through an entire day that I would feel pleasantly buzzed, and not much more, as I Colonial drank away the hours.

I’ve taken my migraine meds and I’m trying to decide if the experiment should go on or if I should call it. I still have afternoon drinks, dinner drinks, and after dinner drinks to go.

5:29 PM

My brother just texted to point out that I’m halfway through, and I’m already on step six in the Drunkard’s Progress: Poverty and Disease. It’s only a short step down until I’m forsaken by friends.

I am trying to drink what a man’s portion of booze for a day would be. Here’s what Rorabaugh has to say about the ladies:

While men were the heartiest topers, women were not faint-hearted abstainers. Little, however, can be learned about either the reputed 100,000 female drunkards or the more numerous women who consumed for one-eighth to one-quarter of the nation’s spirituous liquor. The subject received scant attention because it was ‘too delicate’ to be discussed. The ideal of femininity did discourage tippling, for a woman was supposed to show restraint consistent with virtue, prudence consonant with delicacy, and a preference for beverages agreeable to a fragile constitution. The public was not tolerant of women drinking at taverns or groceries unless they were travellers recovering from a day’s arduous journey. Then the ladies might be permitted watered and highly sugared spirituous cordials.The concept of feminine delicacy led women to drink alcohol-based medicines for their health; many who regarded spirits as ‘vulgar’ happily downed a highly alcoholic ‘cordial or stomach elixir.’

Drinking bourbon on an empty stomach is good for the Constitution.

The American Constitution?

Just like to point out, i would say about 70+% of the food recipes during the 18th century involved sack (the best equivalent today would be cooking cherry) and they used a lot of it. I watch jas townsends and sons on youtube (jas is the short version of james) and he does 18th century reenactments and lots of period correct cooking. It’s fun to watch just how easy their food was to make.

LOVE the chart.. what a great find. I see I am flirting with ruin fairly frequently.

Can’t take credit for digging it up myself! It was handed out at a great lecture on prohibition at the American Museum of Natural History last month. But yes, I do find myself drinking punch and doubting Just Government very frequently.

A Boston-area cocktail store commissioned a special run of the posters from a local movable type letterpress company. I’ve got one in my living room, love it. :)

http://store.thebostonshaker.com/index.php?product=MIBS-TEMP

*Disclaimer, I used to work for the Shaker, but the poster is gorgeous. You might be able to find it elsewhere though

SO nice! My brother (greg) got me a wonderful bar set from the Shaker!

Sara, I worry that you may be overestimating the potency of most alcoholic beverages from this time period. I don’t know about hard liquor proofs from back then, but I do know that most beer and cider were fairly weak compaired to contemporary commercial examples.

The average daily beer was around 3% ABV and most cider tended to be drunk well before full attinuation and so was far lower than the current commercial offerings.

I hate this blackberry.

Spirits were usually of 80-90 proof, but where I got that number, I dunno right

Slohman — you are a national treasure. If Obama doesn’t give you the Freedom Medal this year then I am moving to Canada.

Oh my gosh! I am so honored! Thank you!

Having been a farm kid, I have to say that the eye opener would have been very useful at 5 am, on those cold dark winter days. Breakfast for people doesn’t happen until after breakfast for all the critters.

I’ve been considering the question of why our ancestors drank so much – I mean, aside from celebrations, gatherings at taverns, holidays, etc. It’s interesting that the Royal Navy issued rum rations until 1970, and before they colonized Jamaica, beer or ale rations were issued instead. Rum was found to keep better on long voyages. That doesn’t explain why landlubbers would drink so much. The “polluted water” argument is usually cited and that’s probably true in the cities. However, I’m from Long Island and there are still potable streams from which you can drink the water or even fill up your gallon jugs for use at home. Long Island’s quite well-populated, so I think country dwellers in the States anyway would have had access to fresh water either from natural sources or from wells. I’m reflecting upon Selkie’s comment – much of the United States suffers from dreadfully cold winters. And farming would have been the most prevalent occupation in the Colonial era. I wonder if they weren’t just trying to keep themselves warm by drinking spirits! That may have also been a factor in the navy’s issuing rum – mornings at sea can be bitterly cold. So maybe there was some practical reason for drinking alcohol in the Colonial era, although I think the phrase “medicinal purposes” was already a running joke in the 19th century.

From VictorianWeb.com:

As the April [1868] departure date came closer, Dickens felt tired and acutely homesick. He felt “depressed all the time (except when reading)” and had lost his appetite. On reading days, at seven in the morning he had fresh cream and two tablespoons of rum, at noon a sherry cobbler and a biscuit, and at three a pint of champagne. Five minutes before his [evening] performance he had an egg beaten into a glass of sherry, during the intermission strong beef tea, and afterward soup, althogether not “more than half a pound of solid food in the whole four-and-twenty hours.”

I’m hoping you’ll do some sort of flip or something with a raw egg (although I am not sure whether it’s safe to eat raw eggs)

I have had raw egg drinks before, which are quite tasty, but I’m keeping it mostly simple today. I’m the common man! Also, a pint of champagne???

I don’t think I’d be good for much after a pint of champagne, even if I had a cookie with it. Wow. I have to admit cream and rum does sounds nice… but not nicer than a cup of coffee… though all three together would be fine…

I suppose Dickens was imbibing what the Victorians considered remedies for malaise or maybe stage fright? Raw eggs have long been regarded as a food that “imparts vigor” or somesuch. Apparently pregnant women in Ireland used to drink a raw egg mixed with a bottle of Guinness (nutritionally, not a bad meal, although the egg would probably be more nutritious if cooked). Obviously they don’t do this anymore, but Guinness is still given to pregnant horses in Ireland! Interestingly, Champagne is a celebration drink here in the States, not for everyday drinking, but they order it by the glass in London pubs – I don’t think there are many NYC bars that serve it by the glass. I also find it fascinating that Londoners refer to Champagne not by the trite slang “Champers” as they used to but by its 19th-century sporting man/gay lady epithet: phiz! (although I think they spell it “fizz” nowadays).

Here in Paris it is very common to drink champagne as an apéritif, so much so that simply ordering “une coupe” in a café is understood as champagne.

“I don’t think I’d be good for much after a pint of champagne, even if I had a cookie with it.” I think that’s my favorite quote of the day.

Good health and good fortune to you. Looking forward to further updates.

One of the things I noticed when I was last in Ireland was the prevalence of hard cider as a beverage–on tap and cheerfully consumed alongside the ubiquitous stout. I, for one, would love to see a serious resurgence of hard cider in the US.

Agreed!

I think I would really like to check out “small beer,” the beer that was very low alcohol, more like a carbonated beverage of today. I wonder if it was the equivalent of Lindsay Lohan drinking Kombucha which had a slight alcohol level due to natural fermentation. That might be perfect for a lightweight like myself!

Forgot to ask: do you know if such a thing exists today? Or maybe, we can brew it up ourselves (or some really low-alcohol cider).

p.s. – Please consider liveblogging with Drunken Cellphone Pictures. Haha. :)

I took a terrible photo of myself first thing this morning which i decided not to post! Ok, I’ll try to rally this afternoon and shoot a few photos.

If you look at cookbooks from the early 20th c. (like on the site Feeding America) and look up beer recipes, that will give you an idea of what small beer is. actually, this ginger beer would also be a small beer: https://fourpoundsflour.com/history-dish-mondays-ginger-beer/

I believe Colonial Americans had aspirin, so you wouldn’t be tainting the results of your experiment if you popped a couple Bayers. Not so sure about that DiGiorno’s, though.

I’ll investigate the Colonial DiGiorno’s situation…

We may know today that city water was likely to be contaminated and “country” water was probably less likely to have germs in it (well, depending on where the livestock and privies were in relation to the water source), but it’s vitally important to remember that people in the colonial era had no clue about these things and did not think about health and disease the same way we do. This was many, many years before the germ theory of disease was even thought of.

The folk belief that water was an “unwholesome” thing to drink wasn’t based on whether the specific water in question was “clean” or “dirty” – it was based on then-current assumptions about the way the body worked. (Of course people got the idea that some water was “bad”, but that was usually based on whether there was anything obviously wrong with it that they could smell or taste). So any assumption that people drank alcohol because it was less likely to carry disease than plain water is based on the notion that people had accidentally figured out cause and effect about water-borne diseases – but the overall historical record does not support this idea.

That is an excellent point! The main reason people were getting so sick from water was that we didn’t know better than to not build our privies next to our wells!

Actually, I think many are forgetting that wildlife was abundant in 1830, meaning Giardiasis – Beaver Fever – would have been more frequently found in the streams and ponds. So, in addition to any human activity / occupational waste, there were those already present. Well water here in NWCT has high iron content and requires potability treatment.

Apples did indeed provide the answer and kept the trade imbalance from running too high. Drinking cider and apple brandy were considered to be “patriotic” because it meant America was being self sufficient by not drinking imported spirits. Being publicly inebriated was not disgraceful, it was an example of someone in the pursuit of “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness”. It was the wealthy who created the trade imbalance importing Madeira wine.

Giardia wasn’t called “beaver fever” for nothing. :-)

Nice analysis, TheParsley! That’s the best refutation of the “constantly drunk because water was polluted” argument I’ve ever read. Joseph Bazalgette, who engineered the London sewer systems, is one of the great unsung heros of history. If not for his tireless, exhausting efforts, thousands more would have died of cholera. I am not sure about outhouses and wells, though. Cesspits have been around for a pretty long time – since at least the high Middle Ages, in the UK anyway. Night soil men emptied them, and the job was so disgustingly unappealing that they were paid three times as much as a common laborer. According to Wikipedia, outhouses may have been emptied by night soil men (if they used buckets rather than earth closets), but I don’t know for sure. The alternative would be to build a new outhouse every few years. Nigh soil doesn’t really break down and disintegrate as well as we might hope – as I know from using a disgusting 19th-century outhouse at a riding stable when I was a teen. Between the flies and the stink and the, er, inevitable accumulation, I just wonder if even a Colonial-era person would have built an outhouse near a well? Then again, it wouldn’t have to be all that close to pollute the well. (As an aside, until I Googled “cesspit” I did not realize that Long Island and my home town of Huntington particularly is one of the few places in the world that still uses cesspits! I figured every suburban home had a sunken part of the back lawn where the cesspit is!)

Forgive me for rambling on, I could think about the ponder the plumbing and sanitation all day!

There’s not just the outhouses to think about, but agricultural runoff (fertilizer in fields can contaminate water) as well as a higher level of manure well, everywhere, from country barnyards with chickens and the like (and compost/garbage heaps) to the city with feral dogs and cats, domestic pets and all those draft animals. Proximity of your garbage disposal to your water supply also has an effect on it’s quality.

People were very confused about what was caused disease – at the time they usually blamed “miasma” or bad air, and for most diseases rejected the idea that diseases could be contagious from person to person. Bad water or stagnant water was sometimes blamed, but *only* because it created a bad smell, which was thought to be inherently unhealthy.

In fact, deaths from epidemic disease didn’t become a big problem in American cities until the 19th century, starting with the yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia in 1793. Merely having unsanitary conditions in the city wasn’t enough to cause epidemics – major epidemics came to cities via trade ships and the mobility of people, for the most part. But it was NOT economically advantageous for people to accept that theory, so they blamed swamps and graveyards instead, for emitting “miasmas.”

During the yellow fever in 1793, one scientifically-minded Philadelphian suggested that since the city was so full of lightning rods, that thunder and lightning could no longer properly clear out the “bad air.”

I give them a lot of credit for the “miasma” theory (which is what led to the construction of the London sewer system). It sounds so dumb to us, like the idea that rats sprung from piles of old rags. However, there is a clear connection between revolting sewage, human and animal waste, rotting foods, and bad smells. Sewage or spoiled food can make you very ill, even though the cause is not the smell itself. Nonetheless, if not for the Great Stink of 1858, they would not have built the London sewers. Their reasoning was incorrect – “miasma” was not the cause of cholera outbreaks. Yet the way they chose to combat “miasma,” by replacing cesspits with a sophisticated sewer system, did effectively end the cholera outbreaks. In the 19th century, they did understand that cholera, yellow fever, smallpox, and typhoid were communicable, and of course the plague of the Middle Ages was understood to be communicable. It wasn’t only slave ships that spread disease to the New World. It was also merchant ships trading goods. And as always, disease affected poor people more than the wealthy. There was a certain degree of apathy about poor people dying in hordes and it wasn’t until the wealthy started to be affected by communicable diseases – or in the case of London, Parliament found meeting intolerable thanks to the stench of the Thames – that scientific, medical, hygenic, and social endeavors made eraditicating disease a priority.

There is still “a certain degree of apathy about poor people dying in hordes”, I’m sorry to observe. Or having undrinkable water…

By the way, all the of the colonial mixed drinks are spirits, sugar, and water! So even when they “weren’t drinking water”, they were drinking water.

I completely understand why you couldn’t continue – I feel like crap just thinking about what you did! Drinking, getting the Insta-Hangover, falling asleep, waking up still drunk and hungover at the same time, then having to drink some more… I couldn’t stomach it. I supposed if you were accustomed to drinking this much every day, it’d have been easier, but I am still not sure if you could have made it to the post-prandials (or whatever the working man’s version of that would be – another cider, I guess) without feeling horrid. Maybe you could do the “evening” part of this experiment on another day so at least you can just get drunk and fall asleep instead of having to soldier on through a whole wretched day.

I do look forward to your conclusions!

Horrid is the way to describe it. I pride myself on being able to hold my alcohol, but this regimen really kicked my ass.

I think if you can manage to stick to this schedule for a few weeks you will have it no problem. Im also sure there are plenty of places in NY to hit up an AA meeting. Definitely going to do my best to drink more Porters with meals.

I had the same thought. Like, “Well, maybe if i tried this for a week I’d feel better.” Then I realized I’d be an alcoholic.

This probably also explains why people had wooden teeth and were lucky to make it to 60.

I’m guessing you have to be pretty well acclimated to that level of alcohol intake rather than abruptly starting it out of the blue one day.

I also wonder if a day of hard physical labor would have lessened (or worsened) the effects, but certainly alcohol (particularly the beer/porter/cider type of alcohol) would have been a significant source of calories for the working man. I wouldn’t really want to be nearby when he was swinging a heavy sledgehammer or anything…

I give you credit for going as far as you did. We tend to forget how prohibitively expensive coffee and tea were at one time. It was cheaper in the long run to put something in a cask and ferment it than to buy beverage ingredients by the ounce. Anyone who has spent money at Teavana recently can attest to that. How you suffer for our amusement, er, I mean edification.

Also I hear the tap water in NYC is really great, so have plenty of that and you should be fine.

I wouldn’t have made it past the first drink. Congrats.

Ok, so I don’t have citations for any of this (my bad) but my understanding matches with that of the poster above who pointed out that most early American ciders and beers were much lower alcohol content than what we drink today. I’ve made a small mead and it is lovely, fizzy, and sweet and much lower alcohol than a modern mead. I’m assuming the same would work for cider. Also, of course, the more you drink the more you can tolerate without getting tipsy and ill.

The polluted water argument, while probably accurate (I saw a show recently where they brewed beer from duck pond water and it came out safe to drink and tasty) in that beer made from polluted water is safe to drink, rings false to me. Too much like those appealing historical “truths” that are told in many historic houses about how they were “so much shorter back then” etc. Very appealing but a little too perfect to be true. And, as you point out, they certainly did drink water too!

One thing I read recently, not sure where, was that the reason early Americans drank so much alcohol was that it was a major source of calories in their diet. Obviously they burned a lot more energy than we do today and it had to come from somewhere. Alcoholic drinks pack an energy punch and go down easy. Beer = liquid bread.

Incidentally, Sarah, Colonial Williamsburg is having a conference on Colonial Alcohol in March and it is going to be fantastic (their earlier foodways conference a couple years back was hands down the best symposium I have ever attended). So, i fyou’re looking for an excuse to come down to Virginia…

I did not know about the conference! I should go! I have to look into the dates…

March 18-20

http://www.history.org/history/institute/institute_about.cfm

(scroll down)

Thank you for discovering the true reason colonial Americans did not bathe as frequently as we do – they just kept forgetting!

Next time I would suggest a dry cider – it tastes better and is much less likely to leave you feeling hungover.

I think your commenters have hit on many reasons why the colonials drank more alcohol – there’s no one answer – taste, custom, lack of alternatives (with no canning or refrigeration). I think maybe some of the hard cider wasn’t all that potent (like small beer) and wine was watered down.

I wish I’d thought of this experimental archaeology project when I was in college! Maybe as a semester-long independent study project…

HA! This is one of the few professions were drinking can be called scholarship.

Pingback: Episode 7: Sarah Lohman, part 1 « Alphabet Soup Podcast

I’m a little late to this party, but am a serious enthusiast of all things historical, and especially booze.

My household does a lot of brewing, a lot of food & drink research and reenactment, and we also have a small farm. There are times (usually summer mornings where it hits 80 soon after sunrise) where we’ve been out doing heavy manual labor. A cold beer or cider at 10am seems pretty logical then. We call it channeling our ancestors. The effects dissipate pretty quickly, but the little break and little buzz are refreshing. It’s also a nice way to get some calories without stopping for food, but sometimes we’ll have a hand-held snack too.

Another cold one at lunch, maybe another a couple hours later when it’s time to clean up and get the BBQ going. It makes the work more fun, and no ill effects really.

As for the alcohol content of cider, our homebrew has nothing but fresh-pressed apple juice and yeast, and it usually ends up around 6%. We do an apple-mead (cyser) with juice, honey & wine yeast, and that will knock your socks off.

Great blog btw! Can’t wait to try some of your recipes :)

“…channeling our ancestors” Made me lol. This sounds perfectly logical to me; I often think you can understand the past better when you put yourself in the middle of a similar situation.

And thank you!

It seems to me you did the math wrong, and massively overestimated what you needed to drink to keep up with our forefathers.

Your chart from yesterday shows the total alcohol consumption at its peak (about 1830) was under 4 gallons per year. I’m assuming this is pure alcohol, so (rounding up to 4 gallons a year) that is the equivalent about 10 gallons of 80 proof alcohol a year. Divided over 365 days, gives the equivalent 3.5oz of hard-A a day, which is a little over 2 shots.

Did I do something wrong or were you done by 9:00AM?

Not at all! Most of my information, including the graph, comes from the book “the Alcoholic Republic.” He put this forth as the average of all Americans, which includes women and children. The author suggests that for a male (or many adult females)the average was far higher. Also,it’s been estimated that we drank so much hard cider in the early 19th century that we consumed more pure alcohol from it than any other source.

My agenda from the day also came from period sources reference in the Alcoholic republic. I’ll post the full quote a bit later today. And I highly recommend the book, too–it’s fascinating!

I’ll have to find that book.

This is a much later time period, but still very interesting – http://www.pbs.org/kenburns/prohibition/

After reading the Patrick O’Brian series (Master and Commander et al)set around the 1800’s British Navy, I did lots of research about that time period. Sailors were rationed a gallon of beer per day, which is 8 Imperials 16 oz pints. I can’t imagine firing cannons or setting rigging that tipsy, but I imagine the fear and harsh conditions dampened the buzz quite a bit. http://george-backwell.suite101.com/royal-navy-rations-in-the-early-19th-century–facts–myths-a225339

Pingback: Temperance Reform « History 111:H1, Spring 2012

I’m not certain if anyone mentioned this, but I also think one of the things to do if you attempt this again (or if I attempt it) would be to get up when they used to get up. At like 5 or 5:30 or 6 at the very latest. It’s possible that spreading it out over more time than you did would be easier on the body. Also, maybe try to get more physical movement and labor in there. As was said before, the most common thing was farming, and even if they weren’t farmers, most of the other professions had a fair degree of manual labor involved that we have managed to eliminate from our daily lives. But physical movement helps get alcohol through the system.

Very true. I don’t think the experiment really makes any sense unless you are doing manual labor all day long, and then it is a very different experience I imagine.

Your dedication to research is awe-inspiring! Still, someone’s probably already mentioned this, but trying to keep up with the men probably wasn’t a good idea. My husband weighs maybe all of ten pounds more than me, and he can still drink twice as much. Life wasn’t always fair – then or now.

There’s science behind women’s lower tolerance to alchol! http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=enzyme-lack-lowers-womens

I read a Thanksgiving book to my daughter tonight which prompted me to research the colonial lifestyle. I remembered hearing that they were a bunch of lushes so I googled colonials and alcohol and wala…your blog post came up. I am inspired by your approach to research. That made my day.

Pingback: The apple in colonial America | Rediscovering Life, Awakening to Reality

Pingback: Whiskey For Breakfast and Other Historical Diet Tips - CultureSonar

Pingback: Whiskey For Breakfast and Other Historical Diet Tips - CultureSonar