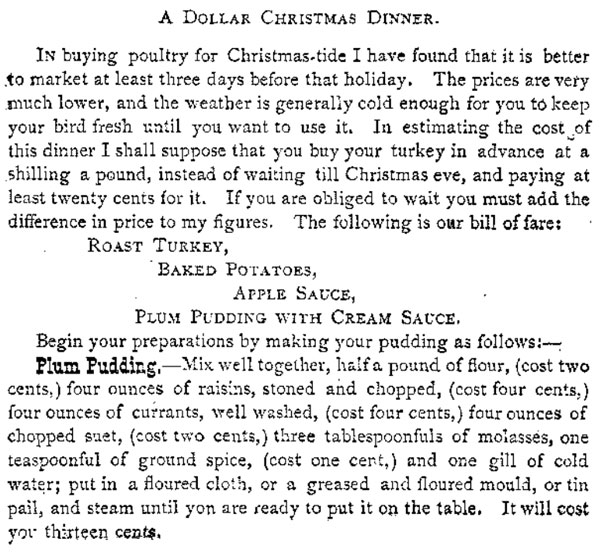

7:06 AM: I’m up. Last night, Temporary Roommate Sarah T stopped by my room and said “I’m going to bed. I’ve left my boots outside my door to be polished, and I expect hot water in the morning to wash my person.” I accused her of being way too good at this and added “If you poop in a pot in your room, I’m not cleaning it up.”

My face is washed and I’m dressed in a black dress and white apron. My understanding is servants did not wear uniforms in the 19th century, but I’m not sure when they started.

I’ve got toast with butter and a cup of tea with milk and sugar. Tea to 19thc servants was like spinach to Popeye.

I’m going to finish my shopping list and meal plan for the day, then do dishes–there’s a sink full of them from yesterday, and if I were a good Maid of all Work, I would not have let that happen.

7:31 AM: In addition to taking cues from Hanna Cullwick’s diary, I’m also going to follow the daily tasks for a Maid-of-all-Work as laid out by Isabella Beeton in her Book of Household Management (first published 1859). You can preview my day’s work here, and here’s what she says about my role:

The general servant, or maid-of-all-work, is perhaps the only one of her class deserving of commiseration; her life is a solitary one, and in, some places, her work is never done. She is also subject to rougher treatment than either the house or kitchen-maid, especially in her earlier career: she starts life, probably a girl of thirteen, with some small tradesman’s wife as her mistress, just a step above her in the social scale…she has to do in her own person all the work which in larger establishments is performed by cook, kitchen-maid, and housemaid and occasionally the part of a footman’s duty, which consists in carrying messages.

I slept in my own bed last night, by the way, but if I were doing this right i should have slept on a cot in the kitchen.

8:15 AM: Dishes are done, cat is fed, and I started coffee brewing at the first sign of stirring in the bedchambers. Here’s what Beeton says I do next:

The general servant’s duties commence by opening the shutters and windows if the weather permits of all the lower apartments in tho housoe,she should then brush up her kitchen range, light the fire, clear away the ashes, clean the hearth, and polish with a loather the bright parts of the range ;doing all as rapidly and as vigorously as possible that no more time be wasted than is necessary. After putting on the kettle she should then proceed to tho dining room or parlour to get it in order for breakfast.

I haven’t cleaned the stove yet, it may have to wait until after breakfast. I’m heading into the “dining room” (read: only common room in my apartment) to tidy for breakfast. Beeton says “Nothing annoys a particular mistress so much as to find, when she comes down stairs, different articles of furniture looking as if they had never been dusted.” Eek. The dusting may have to wait until after breakfast, too.

8:45 AM: Dining room is tidied! I even got in a little dusting. I’m ditching my apron and putting on a little makeup, and heading out to do the marketing. I live in New York, so I have to walk and take a basket with me–not much has changed since the Victorian era.

The dining room is read for breakfast.

The dining room is read for breakfast.

Fiancee Brian just woke up and asked “What’s for breakfast? Is it old timey or is it bacon?”

“Bacon is old timey!” I replied, and is for breakfast. Beeton’s suggestions for a proper breakfast can be read here.

9:30 AM: Back from the store-it’s about a 1.5 mile round trip. Getting up breakfast: toast, butter, jam, eggs (scrambled–poached is more period appropriate, but the Master of the House doens’t like the that way), bacon, fruit, coffee, orange juice.

10:30 AM: Breakfast got on the table, hot, at 10 on the dot. I even put on a clean apron to serve. I left Brian and Sarah T to make idle chit chat, and hit the bedchambers. Opened the sashes and dusted. Changed the sheets in the master bedroom; this room will need more work later. Thus would also be when I would “empty the slops,” meaning the chamber pots, but thankfully it’s 2013 and we have a bathroom.

Next, I’m going to clear and wash the breakfast dishes and sweep and mop the kitchen and dining room floor.

I mentioned to Sarah T that I felt weird that they were talking to me like normal. She offered to jump in to character, but then hesitated and decided she couldn’t order me around. I told them if they needed anything, just to let me know.

I was so hungry when I was cooking breakfast. I’ll have the leftovers–some eggs, a slice of toast with jam, maybe another cup of tea.

In case you were wondering what the rest of the household should be up to while I’m working, here’s a source from 1780–a little early for the Victorian era, but not much would have changed:

I’ll give you an account of one day, and then you will see every day. (Her day began at 9, with breakfast at 10) And then about 11 I play harpsichord, or draw; at 1 I translate at 2 walk out again, 1 I generally read, 4 we go to dine, after dinner we play backgammon, we drink tea at 7 and I work or play on the piano until 10, when we have our little bit of supper, and 11, we go to bed.

12:00 PM: Clear’d breakfast dishes and washed up. Swept whole house–kitchen, living room/dining room, bathroom, and hall. Swept outside hall and welcome mat, too. Brian complained about trash smelling, so I took trash out.

Now it’s time to get dinner up. It’s the largest meal of the day; for a dinner on a Thursday in January, Beeton suggests: ” 1. Vegetable soup (the bones of the beef ribs should be boiled down with this soup), cold beef, mashed potatoes. 2. Pheasants, gravy, bread sauce. 3. Macaroni.” I’m going to sear a beef roast with butter and onions, then cover it up with water, and add half a cabbage, and a butternut squash, salt, pepper, “made mustard” and a slice of toast to thicken it, as per Beeton’s suggested recipe. I’ll simmer low two hours, and when the meat is done, I’ll pull it out and slice it. Soup will be served first, then meat with potatoes and a scoop of macaroni and cheese–blue box, but 19th-centuried up with a blade of mace in the boiling water, and topped with fresh grated cheese and nutmeg.

On my second cup of tea with milk and sugar. Did I mention I only slept about 5 hours last night?

So far the cat has been the most demanding member of the household.

12:35 PM: I also have some veal bones to throw in the soup to make it richer. I’m going to add wine and celery salt. Turns out I have no mustard, or even vinegar, so I put in lemon juice and dried herbs instead. It’s going to simmer for an hour.

Brian was in the kitchen chatting with me; I could barely respond. I was both tired, and focused on getting my task done. I certainly didn’t feel pretty or amorous. I don’t know how Hanna Cullwick did it.

1:45 PM: I am all kinds of achey so I took two Tylenol. Sarah T. just asked if we could have bread crumbs on the macaroni, so I guess I really am 19th-centuring it up and doing it casserole style. I’ve been cooking the last hour. I’m going to sit down and eat at 2; not at the table, but at the kitchen counter. I think Brian and Sarah were to weirded out this morning when I went to do more work while they ate. I’m about to dish up dinner, and I’ll post some photos afterwards.

Brian: “Why are we eating dinner at two??” Me: “Dinner is in the middle of the day.” Brian: “Well, that’s old-timey and weird!!”

2PM: Brian: “Is there bread” Me: “Of course, sir! Right away!” Sarah T: “You have to cut it in front of us, so we know you’re not stealing it.”

3pm: Some photos from dinner.

Mace, for the water to boil the pasta.

Mace, for the water to boil the pasta.

The soup.

The soup.

The Table.

The Table.

Dinner.

Dinner.

3:30 PM: I cleared the dinner dishes and I’m working on washing up. I’ve decided to get my cooking done for the rest of the day–tea and supper are served cold, so if I cook now, I can tidy the kitchen and not have to fuss with it the rest of the day. That involved making a tart for tea, from puff paste I have in the freezer and homemade jam from my mom (here’s Beeton’s recipe) and roasting a chicken to serve cold at tea/supper. Luckily, I don’t have to pluck and gut it.

Neverending dishes.

Neverending dishes.

Fowls to be tender should be killed a couple of days before they are dressed when the feathers come out easily then let them be picked and cooked In drawing them be careful not to break the gall lag as wherever it touches it would impart a very bitter taste…(Mrs. Beeton’s roast fowl recipe)

4:30 PM: I have to admit, that at three pm, I wanted to quit. I am EXHAUSTED. It is unfortunate I didn’t get a full night’s sleep last night, but at the same time I think it’s more accurate to how I would have felt EVERY DAMN DAY if this were my life. I just wanted to quit and go take a nap in my bed.

But I didn’t. And I found a second wind. Chicken and Jelly Tart went in the over. I took out the recycling. I did all the dishes, again. I wiped down the counters. I will keep going until 10:30 pm, when my day is done.

Even Brian is sad. “I don’t like this. You’re my partner–I don’t like you calling me sir.”

I’m even too tired to talk to anyone. I just don’t have the mental fortitude.

5PM: One of the jobs I was supposed to do this morning was shine the boots. I don’t even own any shoe polish, so the best I could do was take three pairs of boots out into the hall and waterproof them, which did need to be done. I also “delivered a message,”by spending a few moments on Facebook inviting a few friends to an Epiphany party on Sunday.

I’m taking a moment to check in with Cullwick and Beeton to see what I’m supposed to do the rest of the evening:

- Finish cleaning kitchen: mop, and wipe down stove and clean oven, when it cools.

- Clean and dust the Parlour

- Clean Window Sills

- Clean Pantry

- Unpack a Hamper

- Tea & Clean Away

- Clean the “Passage” – hang up coats in hall

- Clean “Privy” – Bathroom

- Supper & Clean away

- Turn Down Beds

- Wash sink down

Mrs. Beeton also thinks I should find time to “do a little needlework” but I say screw her.

5:05 PM: I realized I forgot to baste the chicken. Like, at all. motherfucker. I hope it’s not too dry…

6:45 PM: Photos of Tea Time: roast chicken, breand and butter, blackberry jam and puff paste tarte.

Have to clear away, strip the chicken carcass and put away; then, into the passage to hang up coats, then clean the privy.

8:30 PM: Clean’d the bathroom on my knees. My hands are dry and my knuckles and back hurt.

My friend Eva reminded me of this image shot by photographer Hal Hirshorn. Recreated domestic servant at the Merchant’s House Museum. Eva is the model.

10 PM: Supper. Just a little nosh at the end of the day: bread, butter, cheese, cold beef, leftover tart.

10:30 PM:

Finish cleaning kitchen: mop, and wipe down stove and clean oven, when it cools.Clean and dust the ParlourClean Window Sills- Clean Pantry

Unpack a HamperTea & Clean AwayClean “Privy” – BathroomSupper & Clean awayTurn Down BedsWash sinks down

Bet I could have cleaned that pantry if I wasn’t blogging.

And now, I’m going to end my day just like Hanna Cullwick: “Wash’d in a bath & to bed.”

What have I taken away from this? I realized what I did today is about the same workload of your average stay-at-home Mom or Dad.

I’d be interested to hear your thoughts.

Moxy Kitty helps me earlier today.

Moxy Kitty helps me earlier today.

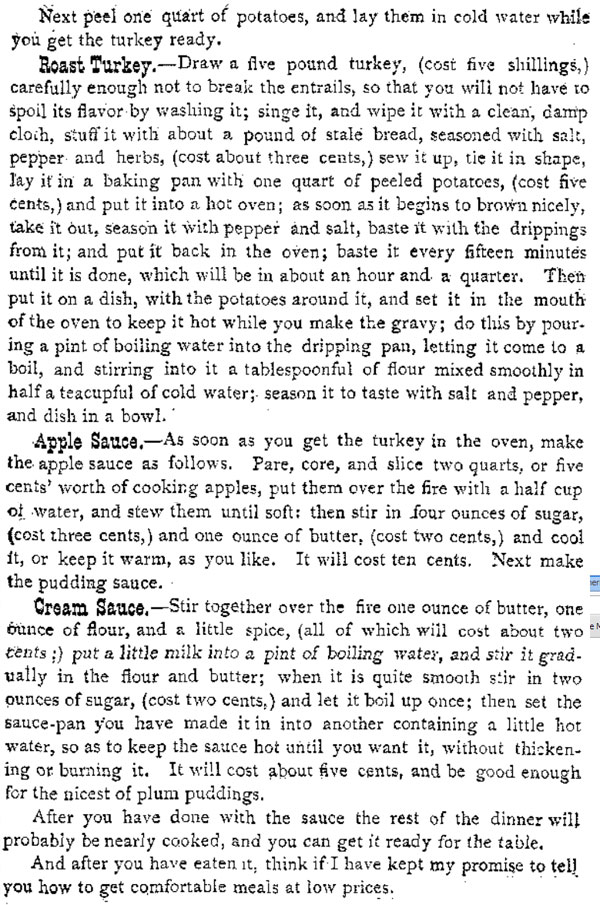

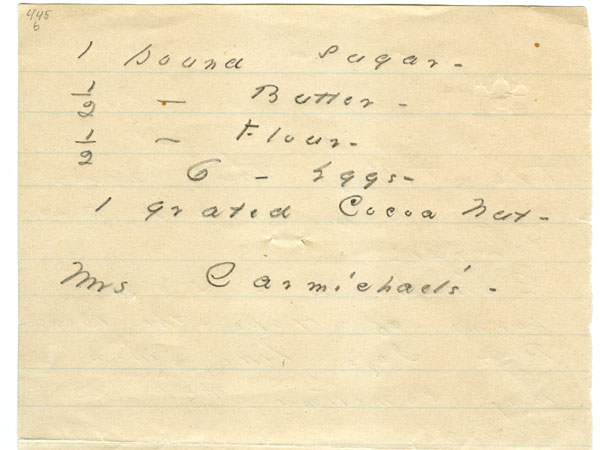

A Silesian Cheese Cake!

A Silesian Cheese Cake! Moxy helps the dough rise.

Moxy helps the dough rise. What is this? I don’t know.

What is this? I don’t know. Mixing the Topping.

Mixing the Topping. Gummy, but decent.

Gummy, but decent.

The Table.

The Table.

The marriage wasn’t made public until Munby’s death, when he willed her his fortune and estate (she was already dead by this point, so it’s all a little confusing). When they were alone, she was the lady of the house. When guests were visiting, she returned to her role as servant. As Bill Bryson describes it in

The marriage wasn’t made public until Munby’s death, when he willed her his fortune and estate (she was already dead by this point, so it’s all a little confusing). When they were alone, she was the lady of the house. When guests were visiting, she returned to her role as servant. As Bill Bryson describes it in